WCAG Heading

by Catharine Arnold

With the death toll rising from Spanish flu, burials at sea became more and more common on the USS Leviathan. Read on for more from Catharine Arnold, author of Pandemic 1918.

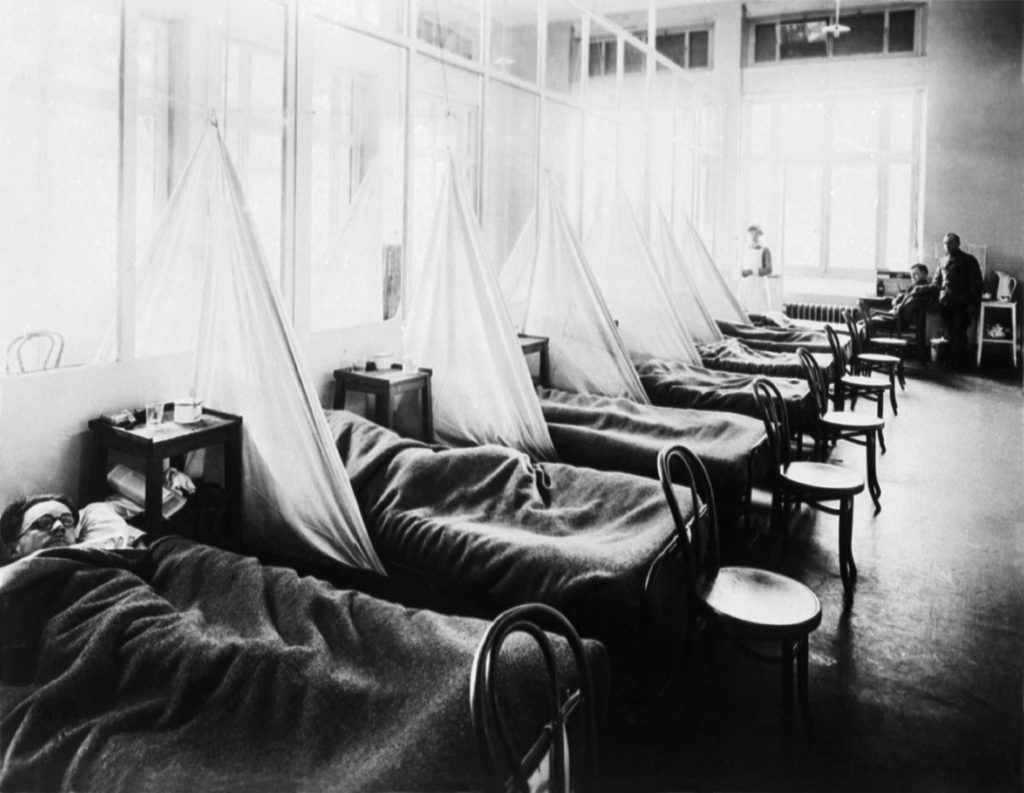

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

The first death from Spanish flu on the USS Leviathan was at 6:08 p.m. on 2 October, when Private Howard Colbert, 11th Battalion, 55th Infantry, was declared dead of lobar pneumonia. ‘He was a sailor who did duty in the Hospital Corps. He told the chaplain that he did not want to die because of the great need of his help at home.’ On the same morning, galvanized into action by this fatality, the army officers ordered healthy soldiers to go down into the holds and clean out the troop compartments and bring out the sick. In an act of mutiny, the troops refused to obey. ‘No threat could be made which filled the men with greater fear than the pestilence loose below.’ But someone had to clean up before the Leviathan became a floating charnel house. Despite tradition, which dictated that the army and navy were separate entities, the ‘bluejackets’ or sailors were ordered below decks to clean up, a task which, to their eternal credit, they performed. Without doubt, their actions halted the progress of the disease. There were no further mutinies among the men: horrified by the impact of Spanish flu, they belatedly recognized that anarchy would make conditions even worse.

From 2 October, not a day passed without a death. Three men died after Private Colbert, then seven, and then ten on succeeding days. The Leviathan’s war diary revealed a new horror: ‘Total deaths to date, 21. Small force of embalmers impossible to keep up with rate of dying . . . Total dead to date, 45. Impossible to embalm bodies fast enough. Signs of decomposing in some of them.’ There was nowhere to store the dead: the morgue was already being used to nurse the living.

Initially, the deaths were carefully recorded in the Leviathan’s log, with details of the victim’s rank and cause of death: ‘12.45 PM. Thompson, Earl, Pvt 4252473, company unknown, died on board . . . 3.35 PM Pvt O Reeder died on board of lobar pneumonia . . .’ But by the time the Leviathan was a week out of New York, the deaths were so numerous that the officer no longer bothered to add ‘died on board’. There were so many deaths that he was simply recording a name and a time. Two names at 2.00 a.m.; another two at 2.02 a.m.; two more at 2.15 a.m.

Identification of the sick and the dead proved impossible. The sick men were too ill to say who they were and although they had all been issued with dog-tags on a chain around their necks, the tags had not yet been engraved with the owner’s name, rank and number. This meant that the names of those who died and those who survived on the Leviathan would never be accurately recorded.

Burials at sea soon became expediencies. Traditionally, burial at sea was a time-honoured ritual, carried out with great solemnity and dignity. But this was soon forgotten in the ongoing horror of the Leviathan’s Spanish flu epidemic. The urgent concern was to get the diseased and decomposing bodies off the ship as soon as possible. One sailor recalled watching similar proceedings on the President Grant from the deck of his own ship, the Wilhelmina. Time after time, after a few muttered prayers, the ship’s colours were dipped, and the plank tipped the shrouded corpses into the sea. ‘I was near to tears, and there was tightening around my throat. It was death, death in one of its worst forms, to be consigned nameless to the sea.’

On 7 October, thirty-one more soldiers died, and the Leviathan finally entered the port of Brest. The ship’s log recorded the grim death toll: ‘Upon our arrival in Brest we had on board 96 dead soldiers and three sailors.’ The healthy and all but the sickest disembarked at once, and 969 patients were removed and taken to army hospitals. The army nurses, who had saved countless lives by putting their own at risk, wept as they walked ashore and ‘bade the sailors an affectionate goodbye’. As the historian of the Leviathan concluded, ‘surely they have earned a place in Heaven’.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Of those who died on board the Leviathan, fifty-eight were buried in France, thirty-three were repatriated to the United States and seven were buried at sea in the war zone. The ship departed from Brest after three days, and on the following morning at sunrise, ‘after an imposing prayer by the chaplain, the flag was half-masted, taps were sounded, three volleys fired and the coffins containing the bodies of the dead soldiers were lowered gently into the sea’. The ship was speeding at 21 knots, as the crew feared the imminent arrival of enemy submarines.

After ‘seven days of mostly fair weather and without trouble from submarines’, the Leviathan returned to New York. The ship’s log concluded, with evident relief: ‘we docked in New York on the morning of 16 October. It was a nerve-racking voyage and we were all greatly relieved that the trip was over.’

There are no clear records of the numbers who died on the Leviathan’s ninth voyage to France. While the ship’s Deck Log lists seventy deaths, the Leviathan’s War Diary gives the figure as seventy-six. The History of the USS Leviathan, written by crew members after the war, states that seventy-six soldiers and three sailors died during the crossing, but in another place it states that the numbers were between ninety-six and three. This confusion may arise from the fact that the chroniclers of the Leviathan were writing about the round trip from France to the United States and back again; or the deaths could simply have been misrecorded as a consequence of the ‘inferno’ epidemic that raged through the ship.

© Copyright Catharine Arnold 2020

Catharine Arnold read English at Girton College, Cambridge and holds a further degree in psychology. A journalist, academic, and popular historian, her previous books include The Sexual History of London, Necropolis, and Bedlam.