by Siân Evans

Siân Evans, author of Maiden Voyages, shares her great-great uncle’s harrowing adventure of being torpedoed by a German U-boat during WWI.

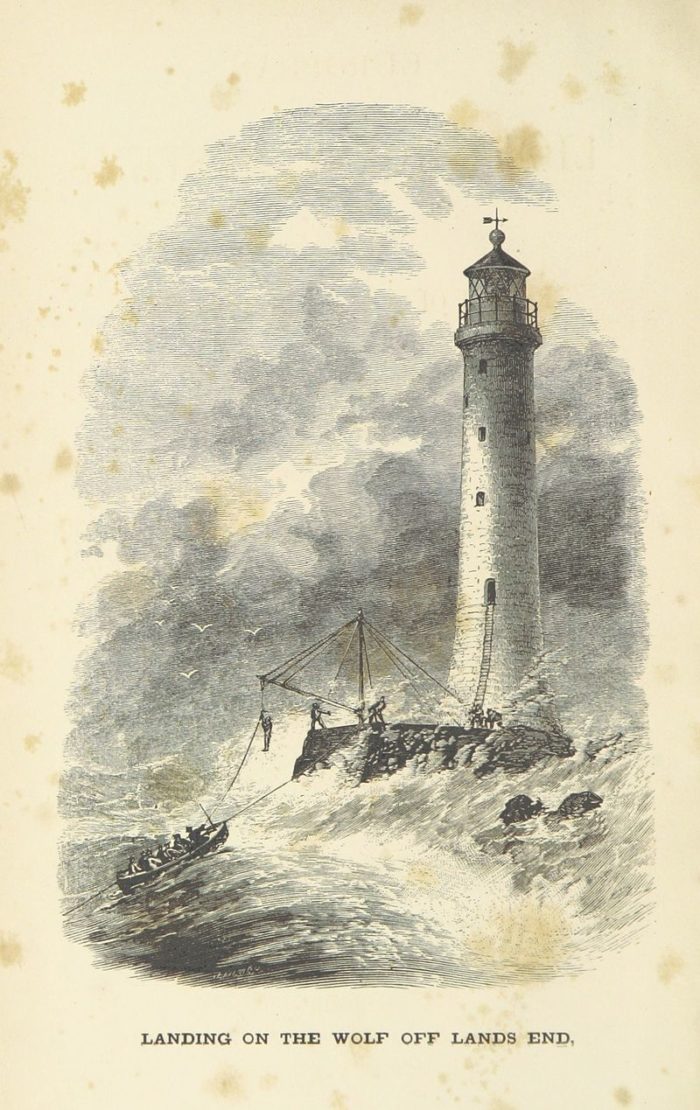

On the afternoon of December 19, 1917, south of the Lizard in Cornwall, as the daylight was fading, Stephen Gronow, the Captain of the Vinovia, spotted the powerful beam from Wolf Rock Lighthouse with some relief. The Vinovia, a ten-year-old Cunard cargo-liner ship, was heading back to London from New York with an enormous cargo of brass and copper for use in the war munitions industry. Gronow, former Chief Officer of the Cunard passenger liner the Aquitania, belonged to the Royal Naval Reserve. Many of his fellow Cunard officers, when war came in 1914, joined Allied warships or undertook naval duties on hurriedly converted merchant vessels. In March 1917, he transferred to become Master of the steam-driven Vinovia, running vital supplies from North America to British ports.

Since North America was vital to the Allies’ war effort, the German Navy was determined to cut off these vital supply lines and targeted the merchant vessels mercilessly. In November 1917 alone, 64 Allied merchant vessels were sunk due to enemy action. German submarines patrolled the coastal waters, tracking and picking off Allied merchant ships carrying supplies, troops and, as in the case of the Lusitania, civilian passengers.

In a desperate bid to thwart the German submarines, the Allies started sending ships escorted by armed destroyers, mounted blockades, laid minefields, and used aircraft as reconnaissance to monitor U-boat bases. They also employed “dazzle paint,” camouflaging the distinctive outlines of ships by painting them with apparently random geometric shapes to make them less easy to spot.

The Vinovia had left New York five days earlier as a part of a convoy and her final destination was to be London. But the voyage had been particularly fraught; the ship had received damage to her rudder and had lost most of her lifeboats due to severe weather. With a top speed of just 12 knots, she had fallen behind as the convoy cleared the southern coast of Ireland and headed for the English Channel. Captain Gronow was well aware of the dangers that might be lurking beneath the waves. He was right to be concerned: just as the winter light started to fade, the solitary Vinovia, lagging behind the armed convoy like a failing animal separated from the herd, appeared in the cross-hairs of a German periscope.

At 3:30 pm, the Vinovia was struck by a torpedo fired from U-105. Nine crew members were immediately killed, and the ship rapidly began to take on water; the decks were awash within 40 minutes. Determined to save the ship and its cargo, Captain Gronow ordered his engines full steam ahead in an attempt to reach the Cornish coast. Some of the crew abandoned ship using the few remaining lifeboats and were picked up by patrol vessels. At 4 pm, a small tug came alongside and made fast to the Vinovia, intending to tow her to harbour. At this point, the remaining crew jumped aboard an accompanying patrol boat, leaving their skipper the only man still on the listing ship, steering by means of the hand gear. For the next three hours, Gronow fought valiantly to head the vessel towards land, being towed in the dark by the tug. At half-past seven, he discovered the forecastle deck already submerged to a depth of four feet. He also realized with horror that the tug had slipped the wire and that the Vinovia was now making no progress. He was therefore powerless and at the mercy of the tides. In making his way back to the bridge again, Gronow was so severely struck by a piece of wreckage that, for a short time, he was rendered unconscious.

On coming round, he made his way to the bridge and put on a bulky cork lifejacket. Here he remained until, at around 8 pm, the Vinovia sank under his feet. He stepped out into the frigid waves of the English channel, clutching wooden wreckage to help him stay afloat. A religious man, Captain Gronow prayed in Welsh, his mother tongue. He wondered what the end would feel like and whether death by drowning was peaceful or monstrous.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Early the following morning, a small patrol boat investigating the Vinovia’s disappearance picked its way through a field of floating debris. The ship itself had vanished completely. They were about to turn back to Penzance, when one of the crew heard the sound of a ship’s bell ringing. As they neared the source of the sound, they spotted the unconscious form of Gronow, his arms still wrapped around the floating mount of the bell.

Suffering from exposure and exhaustion, Captain Gronow was close to death when he was rescued. He was hauled aboard the patrol boat, and prompt treatment in Penzance saved his life. Later, Gronow was awarded the Lloyd’s Medal for meritorious service for his extraordinary efforts to save his ship. The Cunard Board of Directors also gave him a magnificent silver cup, a replica of the famous Warwick Vase. They conferred this award “in recognition of his gallant conduct in endeavouring to save his ship single-handed.”

Stephen Gronow returned to sea at the earliest opportunity following the Armistice. In the following two decades, he sailed past the Wolf Rock Lighthouse many times as he crossed the Atlantic between Southampton and New York. On those peacetime voyages, he often thought with regret of the lost crew and cargo of his beloved Vinovia, and how he very nearly relinquished his own life on that winter’s night.

* * * * *

More than a century after the sinking of the Vinovia, the wreck still lies on the seabed 65 metres below the surface. Salvage attempts have recovered much of its valuable cargo, but what had been a wartime atrocity, and the grave of nine men, is now gradually being reclaimed by the sea.

Listen to an excerpt from Maiden Voyages below!

Siân Evans is the author of several books, including Queen Bees: Six Brilliant and Extraordinary Society Hostesses between the Wars (Hachette UK). Her articles have appeared in many publications, including the Daily Mail, the Daily Express, BBC Antiques Roadshow Magazine, Coast Magazine, National Trust Members’ Magazine, and The Lady. A freelance film consultant for the National Trust, she has an MA in Cultural History from the Royal College of Art, London.