by Greg King and Penny Wilson

Lusitania Prologue

Saturday, May 1, 1915

A rainy twilight fell over New York City on April 30, 1915. Spring was late that year: indeed, an unexpected blizzard had nearly paralyzed the city three weeks earlier. Rushing crowds filled the slippery sidewalks, dodging puddles and splashing water cast off by passing motorcars. Bells on trolleys clanged, horns honked, and horses pulling elegant carriages snorted and stomped along the wet pavement in a cacophony of sound that formed the city’s own unique symphony of life.

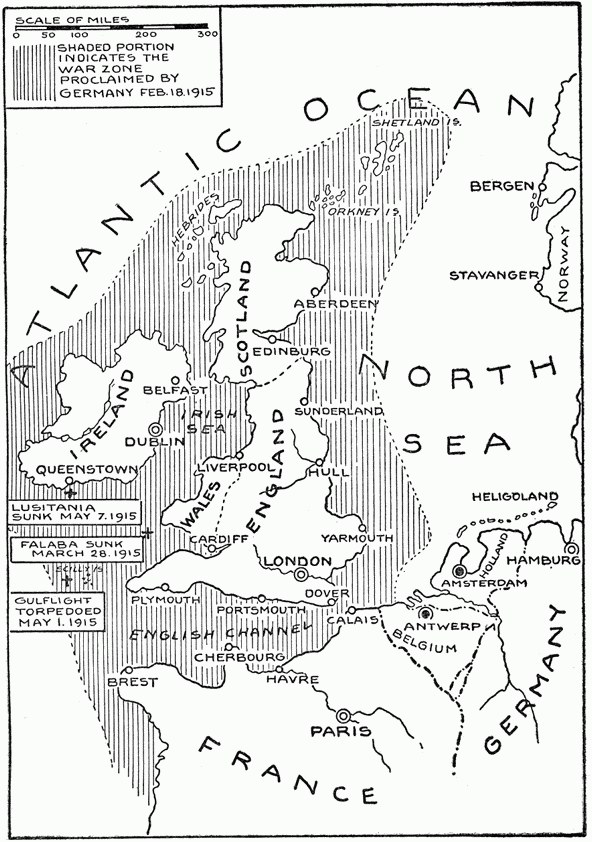

New York City seemed caught in a surreal, parallel universe. Nearly a year earlier, the halcyon days of the Edwardian Era had given way to a new, terrifyingly modern age as the Great War spread across Europe. In muddy fields from East Prussia to Belgium, soldiers exchanged bullets from miserable trenches in a conflict whose scale eclipsed anything ever before witnessed. Despite intense pressure, isolationist, comfortably insular America was still untouched by the distant war. President Woodrow Wilson had insisted that “every man who really loves America will act and speak in the true spirit of neutrality.” Too many people, he declared, would “excite passion” and try to divide the country into opposing camps. Yet official policy could not override widespread worry: how long could America really remain neutral?

Here, in this prosperous, bustling metropolis, a different kind of war was being waged, a conflict between the dying Gilded Age and a new world of clinking cocktails and raucous jazz. Starting in the 1870s, a race of millionaires, speculators, and lavish hostesses invaded New York’s proud old Knickerbocker society, all vying to stun the city with lavish spectacle and voluptuous wealth. The Gilded Age had burst with vibrant color on this sedate and drab world, replacing the “desiccated chocolate” brownstones of respectable society with new palaces of “white and colored marble,” as H. G. Wells marveled.

The exploits of The Mrs. Astor’s famed 400 families of social merit had captivated and amused America for thirty years. They built their ornate palaces on Fifth Avenue and summered in hundred- room Newport “cottages” that, insisted a member, would have made “a Doge of Venice or a Lorenzo de Medici” envious. Society reveled in extravagant parties, sleek yachts, and ever more brazen displays of excess. At a time when an average laborer made roughly $500 a year, one hostess spent $420,000 concealing black pearls in the oysters served to her guests; another piled her dining table high with sand and handed out little silver shovels from Tiffany, bidding guests to dig for party favors of emeralds, diamonds, and rubies. They gave elaborate dinners for their favorite dogs; dressed as their own servants for balls; unleashed monkeys clad in tuxedos to leap upon startled guests; and had meals served while they sat atop horses in decorous hotel ballrooms.

Such antics had once entertained and bemused: now, they repelled. The age of the imposing The Mrs. Astor had imperceptibly slipped into oblivion. Mansions still marched down Fifth Avenue in a parade of ostentatious Renaissance, Italianate, and French facades, but office blocks like the towering Singer, Woolworth, and Metropolitan Life buildings now dominated. Since the controversial exhibitions at the New York City Armory in 1913, the avant-garde had replaced the sentimental in art. The handsome carriages that had once crowded Fifth Avenue had ceded their places to rumbling trolleys and weaving motorcars. Extravagant balls at Sherry’s and fashionable dinners at Delmonico’s had given way to noisy vaudeville revues, whose flirtatious chorus girls became celebrities. Operatic airs and refined waltzes disappeared, replaced by the popular songs of Irving Berlin, the tinkle of ragtime on a piano, and the exotic, sensuously dangerous coming of the Jazz Age.

Bevies of eager young couples, doing their best to emulate the popular Vernon and Irene Castle, fox- trotted, tangoed, and one-stepped across the city’s nightspots. People crowded the burgeoning motion picture houses, watching Mack Sennett’s comedies, the antics of Charlie Chaplin, and the thrilling installments of The Perils of Pauline. The undoubted hit of the year was D. W. Griffith’s epic The Birth of a Nation, a true spectacle that played to a packed house at Broadway’s Liberty Cinema.

Lights flashed and glasses clinked as couples danced that Friday evening into Saturday. There was incessant motion across town as well: throughout the night and into dawn, Pier 54 was a hive of activity. Wagons, vans, and trucks clogged the streets along Manhattan’s West Side, stopping in the shadow of the darkened liner. Just three years earlier, this same pier had been the scene of heartrending pathos, as the Cunard liner Carpathia arrived bearing the lucky passengers rescued from the sinking of Titanic. Now, hour after hour, men deposited cargo, including 250 hefty canvas bags, filled with transatlantic mail. Coal barges drew alongside the hull and spilled their loads through hatchway doors amid grimy black clouds. It took an enormous amount of coal to power the ship: at her top speed, she could consume up to a thousand tons a day.

Wagons and carts delivered goods needed to sustain life during the liner’s seven- day voyage. Passenger bookings had dropped considerably since the start of the war, but the vessel still needed an almost unbelievable amount of supplies: 45,000 pounds of beef; 17,000 pounds of mutton; 4,000 pounds of bacon; 40,000 eggs; 2,500 pounds of pork; 1,500 pounds of veal; 750 pounds of fresh salmon; 2,000 chickens, 150 turkeys, and 300 ducks; three barrels of live turtles; 100 pounds of caviar; 5,500 pounds of butter; 28 tons of potatoes; 6,000 gallons of cream; 3,000 gallons of milk; 1,600 pounds of coffee; hundreds of crates of fresh fruit and vegetables; boxes packed with rare truffles, pâté, crab, and lobster; and case after case of wine and champagne. It was enough to sustain a small army.

Throughout the night, cranes lifted cargo into the liner’s hold. Since the beginning of the war, British owners had used the vessel to transport contraband across the Atlantic. This spring of 1915, Great Britain faced a munitions shortage, and needed American war matériel in its fight. America was officially neutral, but in this case neutrality was a convenient pretense: U.S. industries regularly provided arms and other contraband to Great Britain. According to American law, it was all perfectly legal: a private firm could sell its goods to anyone without violating neutrality. Yet the trade was generally one- sided: few goods or munitions went to Germany. Berlin strenuously and repeatedly complained that the American government, while claiming “an honorable neutrality,” was aiding its enemies, but to no avail.

Read more about the lessons of the Lusitania here

Roughly two thirds of the cargo on this voyage consisted of matériel for military use, including brass, copper wire, and machine parts. Even the foodstuffs shipped in bulk were contraband—at least according to the British government’s own definition of the term. More lethal cargo loaded into the forward holds between the bow and bridge included 4.2 million rounds of Remington .303 rifle ammunition consigned to the British Royal Arsenal at Woolwich; 1,248 cases of shrapnel-filled artillery shells from the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, each case containing four 3-inch shells for a total of some fifty tons; eighteen cases of percussion fuses; and forty-six tons of volatile aluminum powder used to manufacture explosives. According to American law, none of this fell under the category of ammunition forbidden aboard a passenger liner; instead, it was classified as a legal shipment of small arms.

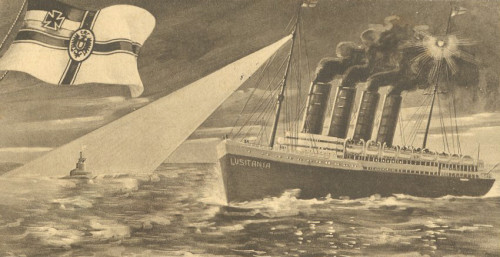

Work continued as dawn broke over New York City, revealing the Cunard Line’s immense passenger liner Lusitania. Her sleek black hull, pierced by innumerable portholes, stretched some 787 feet from a sharply narrowed bow to a gracefully curved stern. Decks of yellow pine and teak crowned a gleaming white superstructure dotted with rows of lifeboats and ventilators; above, four sixty-five-foot- high funnels—raked at graceful angles—towered over the vessel. Once they had proudly sported the distinctive Cunard colors of reddish orange banded in black; now, they were cloaked in drab wartime gray.

Less than a de cade old, Lusitania, an onlooker once marveled, was “more beautiful than Solomon’s Temple, and big enough to hold all his wives.” Subsidized by the British government on the understanding that in time of war she could be quickly converted to an armed auxiliary cruiser, she was immense. At just over 31,000 tons, Lusitania could accommodate three thousand persons, including crew, on her nine decks. At her maiden voyage in 1907, she had been the largest liner ever built, and until 1910 she was the fastest. Lusitania was a triumph: Man, through mastery of the Industrial Age, had finally tamed Nature.

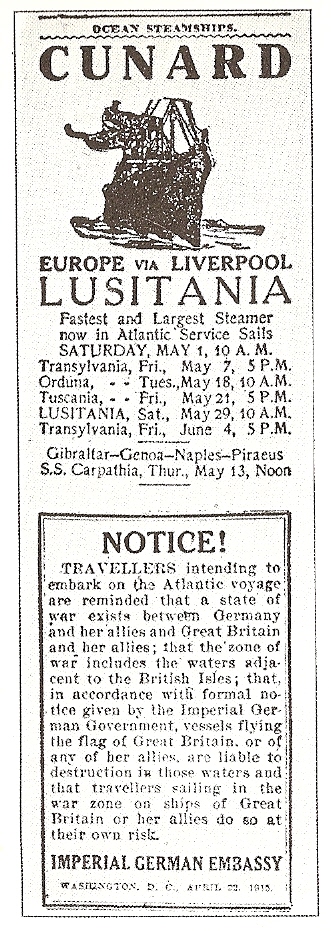

By eight that Saturday morning, Pier 54 was crowded. Although the air was warm, clouds still cluttered the sky, releasing occasional bursts of rain over the scene. Yet not even the weather could dampen spirits as friends and relatives embraced and shouted farewells. “Smartly- dressed officers” moved among the milling crowd as “great truck loads of luggage” and last- minute consignments of mail were rushed aboard. Streets along the Chelsea Piers were clogged with a constant stream of wagons, vans, trucks, motorcars, and taxicabs, dispensing luggage and disgorging travelers destined for Lusitania. Passengers raced past newsstands where young boys loudly hawked the early editions. Within the papers lay an ominous announcement from the German embassy in Washington, D.C.:

It was only an accident— though in retrospect, an ominous one—that the notice appeared next to an advertisement for Lusitania’s voyage. This warning had been the subject of worried debate among German officials in America. Ambassador to the United States Johann, Count von Bernstorff, had received the text several months earlier from Berlin but, “thinking it a great mistake” that would unduly antagonize the country, he had shoved it into a desk drawer and did his best to ignore its existence. In April, Berlin had finally insisted that Bernstorff publish the warning. There was a week’s delay: only on the morning of May 1 did the German notice finally appear in the press. It had, a German spokesman said, merely been “an act of friendship.”

Staring up at Lusitania’s hull, seventeen-year-old Alice Lines, holding tight to a three-month-old girl named Audrey Pearl, was unnerved by the coming voyage. It wasn’t the idea of the crossing itself: there had been frequent journeys across the Atlantic since the British nanny began working for the family of American Frederick Warren Pearl. A former surgeon- major during the Spanish-American War, Pearl had firsthand knowledge of the potential dangers: the family had been in Europe when the Great War erupted, and Germany had arrested Pearl as a spy. He wore English tweeds and carried a copy of The Times of London—all the proof they needed. His release sent the family—Pearl, his wife, Amy, five-year-old son Stuart, three-year-old daughter Amy (called “Bunny”), and one-year-old Susan, along with Alice—back to America, where a fourth daughter, Audrey, was born in early 1915. Now, Amy Pearl was expecting a fifth child as they again set off, this time for London, where her husband was to take up a Red Cross job with the American embassy. Luckily for Alice, a second nanny, a Danish girl named Greta Lorenson, had joined the house hold to help care for the children.

Newsboys shouted the warning, and talk of a possible submarine attack rumbled through the waiting crowd. Still clutching baby Audrey, Alice scanned the German notice. The ship seemed so big and so fast, yet it was hard to forget the possible danger. Now the Germans had practically advertised their intent to sink her. Nervously, Alice showed the notice to her employer’s wife. “Take no notice, dear,” Mrs. Pearl assured her, “it’s just propaganda.”

Others echoed Amy Pearl’s dismissal. Americans, a British journalist declared, were “as safe on Broadway” as they were aboard Lusitania; the warning was merely “a piece of impudent bluff . . . an infantile effort to make Americans afraid.” “Like many other passengers, I gave the notice no serious thought,” recalled Boston bookseller Charles Lauriat. “No idea of canceling my trip occurred to me.” Oliver Bernard, a theatrical scenic designer, saw the warning as he read the morning newspaper over breakfast. He was “not seriously perturbed” by what he imagined was a gesture meant “to embarrass the United States Government and create further consternation in England.” The speed of Lusitania, coupled with “the presence of so many American citizens on board,” he thought, completely eliminated the possibility of a submarine attack. Margaret, Lady Mackworth—returning to Great Britain with her father, David Thomas—paid no attention to the warning: “Feeling ran strong,” she wrote, “and that we should be driven off our own boat by German threats, to take shelter on one of a neutral nationality after we had already booked our passage, was unthinkable.”

The German notice was not the only warning. That morning, thirty-seven-year-old millionaire Alfred Vanderbilt had sleepily struggled out of bed in his luxurious apartment at the Vanderbilt Hotel he had built on Park Avenue. He had spent the previous evening with his second wife, Margaret, at the theater, attending a performance of A Celebrated Case, a new Broadway play produced by David Belasco and Charles Frohman; today, he would sail aboard Lusitania. At eight, the telephone rang. It was Vanderbilt’s mother, Alice: had Alfred seen the notice in that morning’s newspapers? Alfred dismissed it as a joke. His valet, Ronald Denyer, then handed him a tele gram: “Have it on good authority Lusitania is to be torpedoed. You had better cancel passage immediately.” It was signed simply, “Morte.” It seemed absurd, and Vanderbilt dressed in a charcoal gray suit, a tweed cap atop his head, and a pink carnation jauntily adorning his lapel. Photographers and reporters swarmed around his motorcar as it pulled up at Pier 54 later that morning; spotting his friend, millionaire wine and champagne merchant George Kessler, Vanderbilt made his way through the crowd. He pulled the newspaper notice from his pocket, waved it at Kessler, and said, “How ridiculous this thing is! The Germans would not dare to make any attempt to sink this ship!”

Broadway impresario Charles Frohman, whose play Vanderbilt had enjoyed the previous evening, was also bound for Lusitania that morning. “It seems to be the best ship to sail on,” he wrote to a friend in London. Actor John Barrymore unsuccessfully tried to dissuade Frohman from his trip. Barrymore’s sister, actress Ethel, recalled that Frohman’s voyage was “much against everybody’s wishes.” When she’d seen him earlier that week, the impresario told her, “Ethel, they don’t want me to go on this boat,” adding that he had received a message warning him off. He seemed determined to go; when Ethel left, he leaned over and kissed her cheek— something he had never before done. To another friend, Frohman joked, “If you want to write me, just address the letter care of the German submarine.” Now, as he arrived at the pier from his suite at the Knickerbocker Hotel, Frohman faced a bank of reporters. Asked if he was afraid of U-boats, the manager grinned, saying, “No, I am only afraid of IOUs.”

The notice troubled London merchant Henry Adams, head of the Mazawattee Tea Company. With his new wife, Annie, he was to return to Great Britain aboard Lusitania, but now thought a change of vessel might be best. He discussed the situation with Annie and argued that they should take a neutral liner, but his wife, who had relatives employed by Cunard, insisted that they sail as planned. “I have always been a confirmed Cunarder,” she said. Others were visibly anxious that morning. Twenty-six-year-old Dorothy Allen, nanny to the six young Crompton children traveling on Lusitania with their parents, stood at the pier, nervously crying at the idea of a potentially dangerous wartime crossing.

An anxious Sidney Witherbee had rushed to the pier to make one last plea to his brother’s family. Wealthy Alfred Witherbee, president of the Mexican Petroleum Solid Fuel Company, waited for his lovely young wife, Beatrice, their nearly four-year-old son, Alfred Jr., and his mother-in-law, Mary Brown, to join him at their new home in London. Vivacious Beatrice, called “Trixie,” had hurriedly packed up clothing, furs, jewels, silver, porcelain, and linens—a mountain of belongings bound for Lusitania’s cargo holds. The previous night, Sidney had implored Beatrice to take another liner; now, having just read the German notice, he tried again. Beatrice dismissed his concerns: Lusitania was faster than any other ship, and the idea of some submarine successfully attacking her seemed so unlikely.

Immensely wealthy Mary Hammond, too, refused to let the warning dampen the impending voyage: with her husband, Ogden, she would celebrate their eighth wedding anniversary aboard Lusitania. Ogden worried: Lusitania was a British ship, heading into a declared war zone—it somehow seemed foolish to sail aboard her when they could travel on a truly neutral American liner. He had even more cause to worry as they headed toward the ship that morning. A few days earlier, Mary’s aunt had given the couple some stunning news. Count von Bernstorff happened to be a friend; hearing that the Hammonds were to sail to Europe, he had apparently warned her aunt, “Do not let anyone you know get on the Lusitania.” Mary thought it was a joke, but Ogden took the warning seriously enough to ask an official at Cunard Line’s New York office about the potential danger. Traveling aboard Lusitania, he was assured, was “perfectly safe, safer than the trolley cars.” Ogden wasn’t convinced: together with his brother, John, he tried his best to change his wife’s mind. If Mary insisted, John said, at least she should have a will: she was a millionaire, with three young children, Mary, Millicent, and Ogden Jr. And so that Saturday morning, John came aboard Lusitania, presenting Mary with a hastily drawn-up document to sign before the ship sailed.

Mary dismissed the warnings; so, too, did others. A few days earlier, two British cotton dealers working in Texas had boarded a train bound for New York: bulky Robert Timmis was delighted that his friend and fellow dealer Ralph Moodie would also be sailing on Lusitania. A few years earlier, Timmis had been blinded in one eye, but nothing could keep him from his annual trip to Europe. Now, he jokingly told his wife, “We may be torpedoed on this trip, but don’t worry. If we should be, we probably will be near the Irish coast.” Even when he saw the German notice that Saturday morning, Timmis maintained an air of jovial dismissal. “We thought little about it at the time,” he recalled, convinced that he was embarking on “just another journey.”

Canadian Thomas Home was glad that he’d woken early: “Never before,” he wrote, “have I seen so much crowd and so much baggage.” The buyer for a Toronto department store had just missed being on Titanic three years earlier. Now he shuffled along the pier under the watchful eyes of Cunard officials who examined tickets; this, he knew, was unusual—and not a reassuring sign, especially in light of the German notice.

Mountains of leather valises and wicker cases, steamer trunks and hatboxes, arrived throughout the morning. They contained all the worldly belongings of some passengers, setting off to embark upon new lives in the Old World; many more, though, were filled with a wide range of clothing and accessories necessary to maintain the sartorial traditions and comforts of First Class. Trunks ticketed “Not Wanted” were separated and hoisted into the cargo holds, while stewards supervised as those needed during the voyage were taken to cabins.

These trunks and suitcases were a source of potential worry. Would a German spy or saboteur conceal some infernal machine amongst stockings or handkerchiefs? Security this May 1 was especially tight. Detectives checked papers and tickets before allowing passengers to approach the ship; luggage had to be personally claimed and identified before it was loaded, and all handbags, packages, and parcels were searched. Officials waiting at the foot of gangways double- checked tickets and papers before allowing passengers aboard. Yet such measures were apparently haphazardly enforced. Forty- seven- year- old former deputy sheriff Michael Byrne, off to visit relatives in Ireland, arrived at the pier with his German- born wife and several friends, a large steamer trunk, two suitcases, and an umbrella bag. “No officer or anyone else questioned me or asked about my baggage,” he recalled. Nor did anyone stop his wife and friends from following him aboard to inspect the ship. Charles Lauriat was equally surprised when two members of his family, who had come to see him off, were also allowed to join him aboard the ship without any questions being asked.

Crews cranked newsreel cameras as passengers shuffled along the pier; a few photographers, noting the German warning, joked that they were going to entitle their images “The Lusitania’s last voyage.” Charles Sumner, general agent for the Cunard Line in New York, seemed equally lighthearted. There was, he insisted, “no risk whatsoever” by sailing aboard Lusitania. The ship, he promised, could make 25 knots; this was “too fast for any submarine. No German vessel of war can get near her.” As for the notice, Sumner—pointing at the lines of passengers—laughingly said, “You can see how it has affected the public.”

High on the liner’s gently curved bridge, Captain William Turner surveyed the last-minute preparations. He dismissed worries that his ship might be in danger heading into a war zone patrolled by German U- boats as “the best joke I’ve heard in many days.” Turner was cavalier when questioned about the German notice and potential danger: “I wonder what the Germans will do next?” he mused. “Well, it doesn’t seem as if they have scared many people from going on the ship by the looks of the pier and passenger list.” Lusitania, he insisted, was entirely safe. “Do you think all these people would be booking passage on board Lusitania if they thought she could be caught by a German submarine?” he asked reporters. “Germany can concentrate her entire fleet of submarines on our track and we would elude them.” Besides, he added, “we shall be going faster than any submarine can travel; therefore, they are not likely to sneak up on us.” As the crew bustled over the liner’s decks preparing for the voyage, a few of the more superstitiously minded whispered a piece of ominous news: Dowie, the ship’s four-year-old black cat and unofficial mascot, had disappeared the previous night, and no one had seen him since.

Lusitania had been scheduled to sail at ten that morning. On this voyage, she would carry the largest number of passengers since the beginning of hostilities.(57) Some were off to join the fighting in Europe; others were hoping to join relief efforts, or traveling to re unite with loved ones who were destined for the battlefield. But surprisingly, and considering the state of war and the risks of traveling through an area patrolled by hostile U-boats, many passengers sailed aboard Lusitania for holidays and family reunions.

Following custom, the 373 Third Class passengers had begun forward boarding first, just after seven. “This is not, as has been unkindly suggested,” a guidebook warned, “because they only pay low fares, but because there are so many of them, because the number of children in that class is proportionately greater than in any other, and because sufficient time must be allowed for them to settle down before the voyage begins.” An hour later, the 601 Second Class passengers embarked, climbing gangplanks at the rear of the vessel. Helpful stewards examined tickets and directed people down decks and along corridors to their cabins.

The 290 passengers traveling in First, or Saloon, Class began arriving shortly before nine. This, as one contemporary noted, “is a more ceremonious affair, for they sometimes include persons of title, holders of high naval or military rank, colonial governors, millionaires, and even members of reigning families. Their arrival is interesting because there is about it a survival of the etiquette of the sailing- ship days, when the owners of the ships saw personally to their departure and were always careful to escort any exalted personages to the ship’s side and present them to the captain.” They disappeared into the pier building, temporarily shielded from clicking cameras as they presented papers and steadily neared the open doors at the side. Emerging into the light of day, they climbed narrow gangways above the dark Hudson that seemed to vibrate ominously with every tread. Once they had entered the hull of the vessel, crisply uniformed officers waited in the First Class Entrance Hall, decorously welcoming these ladies and gentlemen aboard the great Lusitania.

“Such last minute excitement!” was how an earlier traveler described the scene aboard Lusitania. “All was confusion—stewards and stewardesses guiding passengers with their suitcases to their staterooms, lifts going up and down, bustle, noise, and hurrying everywhere.” Stewards rushed along corridors, bearing an assortment of farewell gifts sent on by friends and relatives of those sailing that morning. There were immense bouquets of flowers; bottles of fi ne wine and vintage champagne; carefully wrapped boxes of candy or hot house fruits; packages of books; collections of teas from around the world; decorative tins of delicacies like caviar or exotic tropical jams; and a multitude of cards and letters wishing travelers a memorable voyage.

More than a few passengers clustered in Lusitania’s Reading and Writing Room that morning. Architect and spiritualist Theodate Pope sat there with her traveling companion, Edwin Friend, browsing through the newspaper, when she spotted the German notice. “That means, of course, that they intend to get us,” she commented. Others penned farewell notes and letters to friends and relatives, to be sent off the ship when the pi lot departed: these were the people who, as Lady Mackworth thought, were “fully conscious of the risk we were running.” Elaine Knight, traveling with her brother Charles, wrote out an eerie postcard to her niece: “I am mailing you this card just as we are going on board the Lusitania. Will write as soon as we reach the other side, if I am still alive.”

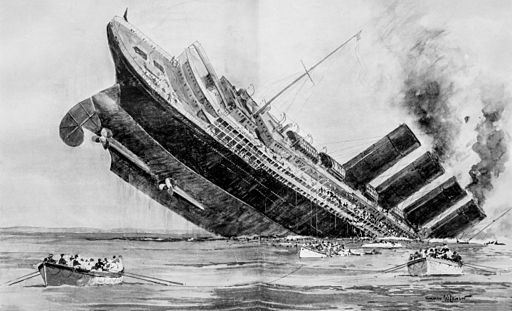

There was an unexpected delay that morning, when word came that the British Admiralty had abruptly requisitioned Cameronia, a smaller liner that was to sail from New York to Glasgow, to use as a troop transport. Forty- one of her passengers and their baggage were transferred to Lusitania. The delay, Oliver Bernard noted, created some tension as people again worried over safety, though Cameronia’s former passengers were “obviously delighted” to find themselves aboard “a faster, and therefore safer, ship.” In all, 1,264 passengers sailed on Lusitania, less than half of her actual capacity; with a crew of 702, which included the ship’s five musicians, this brought the total to 1,966. By noon, morning rain gave way to patches of sunshine, as a boy wandered over the ship shouting, “All ashore that’s going ashore!” Passengers lined Lusitania’s decks, shouting farewells and waving handkerchiefs to onlookers below. “It was almost like a personal triumph,” a previous passenger remembered, “to be one of those who stood at the rail, looking down. . . . You were a part of the ship itself, although you were hardly more than a pinhead along the great expanse of deck rail.” An “eager, restless movement of the throng” aboard ship always marked such departures. Writer Theodore Dreiser likened the experience to “the lobby of one of the great New York hotels at dinnertime” as people scampered and scrambled.

“Bells were ringing their signals for final preparation,” Phoebe Amory remembered. “The shrill blasts from the tugboats announced that they were ready to begin their labor of moving the great ship from her moorings, and the deep, throaty reply from the chimes of the Lusitania voiced her assent.” Hatches were sealed, gangways pulled in, lines hauled up, and doors closed as the ship readied for her voyage. Cameras clicked and men along the pier cranked their newsreels, capturing Captain Turner as he looked out from the bridge.

Deep below, a grimy contingent of shirtless trimmers rushed wheelbarrows filled with coal from bunkers to boiler rooms. Mustachioed Chief Engineer Archibald Bryce shouted orders and watched the gauges as stokers relentlessly fed the fuel into Lusitania’s blisteringly hot furnaces. Everything “clanked and rattled and hissed and squeaked” as the ship built up steam. A deep rumble shivered through Lusitania as her steam turbine engines came to life.

Members of the Royal Gwent Singers, returning home to Wales after an American tour, loudly sang “The Star-Spangled Banner,” while the ship’s five-man band launched into “Tipperary” as the crowd along the pier cheered and waved. Three little tugs gently eased the black hull out into the Hudson. Gulls swooped and circled as Lusitania’s four immense bronze propellers twisted and turned, churning behind them a wide wake of foam. Slowly, surely, Lusitania steamed past Ellis Island, the Statue of Liberty, and what Theodore Dreiser deemed “the magnificent wall of lower New York, set like a jewel in a green ring of seawater,” as the city receded in the distance. Smoke curled from her funnels and waves furrowed against her bow as Lusitania picked up speed. Across the Hudson, a line of German passenger liners, kept at dock for fear that British cruisers patrolling the waters outside of America’s three-mile limit would sink them as potential enemy auxiliary cruisers if they attempted to return home, attracted much attention. With the sun now shining on the brass letters of her proud name, Lusitania was on her way out of New York, bound for Liverpool on her 101st return voyage.

GREG KING is the author of eleven internationally published works of history, specializing in late Imperial Russia and on social history. A frequent contributor and onscreen expert for historical documentaries, he serves as Editor-in-Chief of the bi-monthly European Royal History Journal, and his work has appeared in Majesty Magazine, Royalty Magazine, Royalty Digest, Atlantis Magazine, and the European Royal History Journal. His newest book is The Assassination of the Archduke.

PENNY WILSON is the author of three internationally published works of history devoted to late Imperial Russia. Her historical work has appeared in Majesty Magazine, Atlantis Magazine, and Royalty Digest.