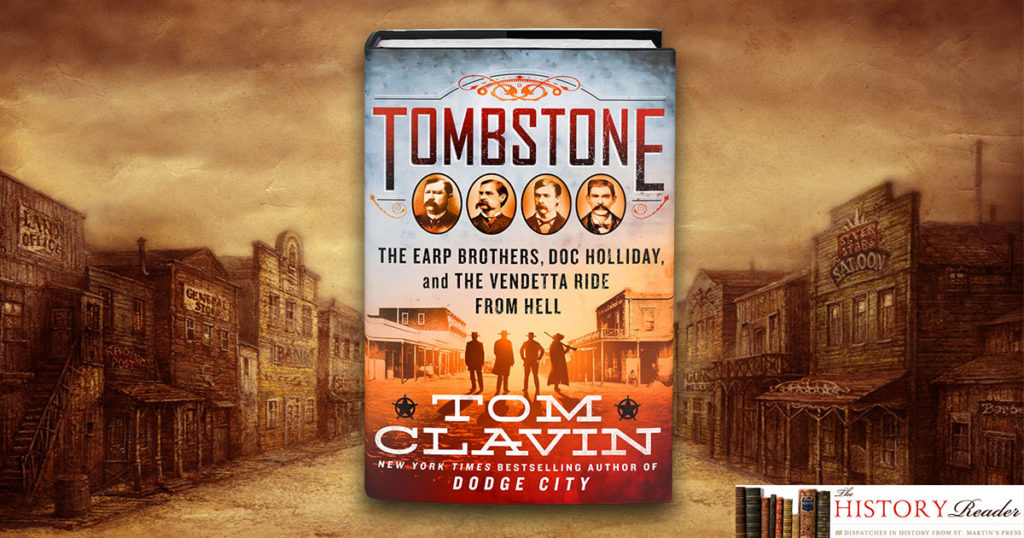

by Tom Clavin

In an excerpt from his latest book, Tombstone, Tom Clavin discusses the Earp family’s arrival in Arizona, focusing on Virgil Earp’s initial acts as a lawman.

The Earps’ early days in Tombstone were not auspicious ones. An immediate disappointment was where they first lived, which was a humbling comedown from their Dodge City and Prescott accommodations. One can understandably imagine the Earp women wondering, “We came to Arizona for this?” If their situation had not improved, it is likely the brothers would have elected to move on to seek their fortune in the next boomtown, and the history of the American West would be much different.

In what must have been extremely cramped and intimate quarters, the extended family resided in a small house. It was all they could afford, and even at that, in a boomtown it did not come cheap. As Allie described it, “We happened on a one-room adobe on Allen Street that some Mexicans had just left. It didn’t even have a floor—just hard packed dirt, but it cost forty dollars a month. We fixed up the roof, drove the wagons up on each side, and took the wagon sheets off the bows to stretch out for more room. We cooked in the fireplace and used boxes for chairs.”

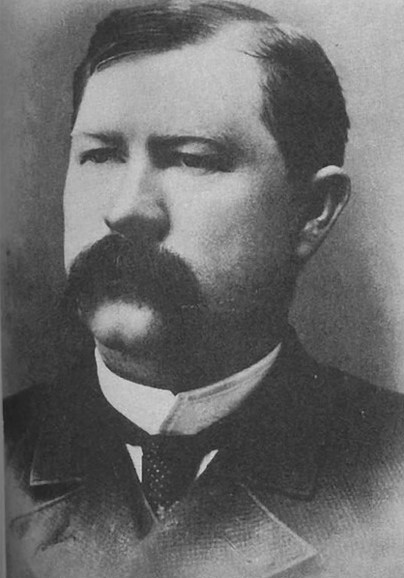

This photo is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

The spunky Allie was not about to sit around and wring her hands about the employment status of the menfolk. It turned out to be fortunate that she had insisted on bringing her sewing machine along. Allie was hired to make a canvas tent for a new saloon. This project turned out fine enough that others in the town began giving her jobs, and she hired Mattie to assist her. The money they brought home helped the Earps stay afloat until more revenue came in. Allie would crow, “That big canvas tent with its double rows of stitching changed our luck.”

Virgil had his occasional federal pay and secured jobs as a wagon driver. And because Tombstone was a boomtown, before long James found a job dealing faro and bartending in a saloon. Wyatt began gambling, but it was more as something to pass the time until less risky employment came along. Finally, he was offered a job as a Wells Fargo stage guard. Wyatt surely had not anticipated such a position, but he had been a shotgun messenger before, while on sabbatical from Dodge City lawing, and with all the cash being transported, men with experience were welcomed. What he also could not have anticipated was how his renewed connection to Wells Fargo would benefit him in the near future.

The trickle of money coming into the Earp household became a stream, but the men weren’t necessarily happy about it. As Casey Tefertiller points out, “They had arrived seeking fortune, not wages.”

Still, the brothers were better able to put food on the table, and the living became easier for their women. “Within a few weeks Mattie considered herself settled, content to lead a quiet life, and she remained so throughout her entire stay,” contends E. C. (Ted) Meyers. “Although she was admittingly drinking (she and Allie are known to have shared many an afternoon nip) she kept it private. As in Dodge City, her stay in Tombstone is notable mainly for its almost total anonymity.”

Some of this was by design. Although Tombstone was a relatively new frontier town, far from the social mores of society to be found east of the Missouri River, Allie and Mattie had become Earp wives without real weddings, and the only occupation Bessie had known in her adult life was as a prostitute and brothel owner. There was a strong element in town, which included the wives of prominent businessmen, who wanted Tombstone to become respectable, to be a civilized community in which to raise children, educate them, and attend churches as families. The Earp women were from the wrong side of the tracks. And that posed a problem for the brothers’ financial and social aspirations.

“While a man and woman lived together as common-law husband and wife, no one questioned their standing as a couple,” explains Jeff Guinn. “But in territorial towns of any consequence, there would always be a small, select upper class of investors and merchants, and these men often did bring their wives with them, women who were married in every legal sense. Formally married women might associate in a reasonably friendly fashion with common-law wives, but they would rarely invite them into their homes.”

Allie tells of a day that she and Mattie broke free of their tiny box of a home to stroll through the downtown area, admiring displays in the storefronts and the menus posted outside hotels and restaurants. When Wyatt found out about their escape, he was furious. Their women were not to be representatives of the Earp brothers and risk thwarting the respectability they, particularly Wyatt, intended to acquire. As Guinn adds, “The things he wanted—money, social prominence, importance—were far more likely to be found within Tombstone’s town limits.” And the women needed to be cloistered in the claustrophobic home limits, not strutting about.

The U.S. Census figures for Pima County in 1880 listed Alvira Earp, Bessie Earp, Hattie Earp (Bessie’s daughter), James Cooksey Earp, Mattie Earp, Virgil Walter Earp, and Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp. Allie’s, Bessie’s, and Mattie’s occupations were given as “Keeping House,” James was a “Saloonkeeper,” and “Farmer” was the fanciful occupation given to both Virgil and Wyatt.

By the time the census was taken, the Earp family members had dispersed. With almost everyone working and earning fairly steady pay—Bessie probably did most of the “Keeping House” while caring for her daughter—they could afford their own homes. But these were the clannish Earp brothers, so they were not about to spread out too far. Virgil and Allie found a house at the southwest corner of First and Fremont Streets, Wyatt and Mattie lived on the northeast corner, and James and Bessie were only one block away.

They would soon have company. After Morgan resigned as a peace officer in Butte, he did not come directly from Montana but detoured to the Earp homestead Nicholas and Virginia had set up in San Bernardino County in California. Morgan left Louisa there, unsure if her fragile health was ready for the rigors of life in southeast Arizona. Even though Allie liked the boyish Morgan, upon his arrival in Tombstone she now had four clannish Earp brothers together, and word was that the youngest, Warren, might soon be on the way.

This photo is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

The only official lawman of the family, Virgil, found himself becoming busier. According to the March 26 edition of The Weekly Arizona Miner, one of the territorial newspapers that included Tombstone news, “Deputy U.S. Marshal V. W. Earp arrested a man by the name of C.S. Hogan at Tombstone, a few days since, for counterfeiting trade dollars. He was examined, held to bail in $5,000, but escaped from the Tombstone prison. The plates and dies were found with the prisoner.” As we shall see, the porous walls of the Tombstone jail would be a persistent problem.

There were times, though, when the sturdiness of the jail did not matter…and that Tombstone could still be a rough-and-tumble town. A FATAL GARMENT was the headline of an article in the July 23, 1880, edition of The Tombstone Epitaph, and Tom Waters had the misfortune to be wearing said garment.

He and E. L. Bradshaw were both miners and friends who had the worst kind of falling-out. On the morning of July 22, while in town, Waters bought a blue-and-black plaid shirt and, quite proud of himself, wore it on what was apparently a day off from digging for silver. The colorful pattern was a tad loud, and passersby remarked on it, irritating the wearer. The peeved Waters sought shelter in Tom Corrigan’s saloon on Allen Street, where he declared the next person to comment on his new shirt would get a sock in the jaw.

In walked Bradshaw, who innocently complimented his friend on the new garment. Waters’s aim was off, and he hit his friend above the left eye. The effect was the same, though: Bradshaw fell unconscious to the dirt-filled floor. He remained there as Waters left. He visited other saloons, announcing his continuing displeasure at the reception his shirt received. When Waters weaved back to Corrigan’s, Bradshaw was gone.

The abruptly former friend, after shaking himself awake and rising from the floor, had returned to his cabin, washed up, and found his pistol. When he arrived back at Corrigan’s, he found Waters standing at the saloon’s entrance. When asked, “Why did you do that?” Waters replied with a string of oaths. They were interrupted by the sound of gunshots as Bradshaw fired, altering the blue-and-black pattern to include four bullet holes. Waters was dead before he hit the wooden sidewalk. Bradshaw submitted to arrest, but a grand jury refused to charge him with murder—perhaps some of its members had gotten a gander at the dead man’s shirt.

In addition to catching counterfeiters, Virgil performed other lawing duties capably; then came an event that would have far-reaching consequences. That same month as the Waters killing, six army mules were stolen. The commander at Camp Rucker, the stockade once known as Camp Supply, assigned Lieutenant J. H. Hurst to take four soldiers and go find the purloined property. The young lieutenant was smart enough to assume that the crime had been committed by cowboys and that he should have help. His party rode to Tombstone and Hurst looked up Virgil, who agreed that the deputy U.S. marshal should be in on the hunt. Virgil in turn deputized a posse to swell the number of searchers—his brothers Wyatt and Morgan and the local Wells Fargo agent, Marshall Williams.

The nine riders set off, stopping at ranches along the way. On September 25, the searchers arrived at the Babocomari ranch belonging to the McLaury brothers. It was bad enough for the owners that the six missing mules were there; worse, ranch hands were in the process of changing the brands on them. If this had been up to Virgil, there would have been immediate arrests. But this had originated as an army matter. To Virgil’s disappointment, Hurst was persuaded by Frank Patterson, a Babocomari foreman, not to arrest anyone and to await the return of the mules in Tombstone.

The gullible officer may have been the only one surprised when the mules did not show up—but Patterson, the McLaurys, and their young friend Billy Clanton did, to taunt Hurst for being such a rube. Instead of immediately repairing to the ranch to seize the mules, the army officer, perhaps believing the pen was mightier than the saber, created and posted notices naming several men as the thieves and adding that they had been assisted by the McLaurys. Making the matter more farcical, Frank McLaury paid for a notice published in the Tombstone Daily Nugget that defended the integrity of his ranch and his own honesty and alleging that Hurst had himself stolen the mules. He further contended that the officer “is a coward, a vagabond, a rascal and a malicious liar” and the “base and unmanly action is the result of cowardice.” McLaury looked forward to the matter being “ventilated” so the truth would emerge.

This incident, even with McLaury’s rancor, could have been settled over a couple of drinks, but it took an extra serious turn that would later be seen as a catalyst for the gunfight thirteen months later. Not satisfied with the power of the press, Frank McLaury looked up Virgil, accompanied by his brother Tom. Hurst, they believed, was not their only enemy.

“If you ever again follow us so close as you did,” Frank McLaury said, meaning Virgil and his posse visiting the ranch, “then you will have to fight anyway.”

“If ever any warrant for your arrest were to be put in my hands,” Virgil responded, “I will endeavor to catch you, and no compromise will be made on my part to let you go.”

Frank said, “You’ll have to fight, and you’ll never take me alive.”

Copyright © 2020 by Tom Clavin

Tom Clavin is a #1 New York Times bestselling author and has worked as a newspaper and web site editor, magazine writer, TV and radio commentator, and a reporter for The New York Times. He has received awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, and National Newspaper Association. His books include The Heart of Everything That Is, Halsey’s Typhoon, and Reckless. He lives in Sag Harbor, NY.