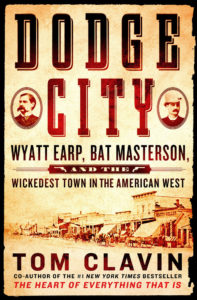

by Tom Clavin

The word “gunfighter” in America can be traced back to 1874, but it wasn’t until around 1900 that it was more commonly used. The term that most people used in the 1870s was “shootist,” or the more specific “man killer.” An example of one was John Wesley Hardin.

Hardin spent some time in Dodge City, but he was more associated with Texas and another Kansas city, Abilene, where he had been photographed before escaping the long gun of Wild Bill. By then, the son of a Methodist preacher was already a veteran man killer. In 1867, his precocious criminal career had begun at age fourteen, when he was expelled from school for knifing a classmate. The following year he gunned down a former slave on an uncle’s plantation in Moscow, Texas. Three army soldiers were dispatched to arrest him. Hardin ambushed and, depending on the account, killed one or all of them.

The saying “I never killed a man who didn’t need killing” has been attributed to Hardin, and he obviously lived in needy times because he is “credited” with sending as many as thirty men to the hereafter. A few were killed while he worked as a cowboy on the Chisholm Trail; there was that one man dispatched in the hotel in Abilene; and he had a run-in with some lawmen in Texas. But then he seemed to go straight, marrying a Texas girl in Gonzales County, and they had three children.

But for Hardin, domestic bliss didn’t last. A killing spree ended the lives of four men, and he was arrested in Cherokee County by the sheriff. He escaped from jail, fled to Brown County, where he killed a deputy sheriff, and, after collecting his wife and kids , he went east, to Florida. It wasn’t until 1877 that Hardin was located and arrested, in Pensacola by Texas Rangers. He was found on a train, and when he grabbed his pistol it got caught in his suspenders. His companion, nineteen- year- old James Mann, was less clumsy but also less of a marksman. His bullet went through the hat of Ranger John Armstrong, who shot Mann in the chest, killing him.

, he went east, to Florida. It wasn’t until 1877 that Hardin was located and arrested, in Pensacola by Texas Rangers. He was found on a train, and when he grabbed his pistol it got caught in his suspenders. His companion, nineteen- year- old James Mann, was less clumsy but also less of a marksman. His bullet went through the hat of Ranger John Armstrong, who shot Mann in the chest, killing him.

After being convicted it was hard time for Hardin, seventeen years of it in the state prison in Huntsville, where among other occupations he studied law and headed the Sunday school. When released, he was admitted to the Texas bar and opened a law practice. During his incarceration his wife had died, so he was free to marry, which he did to a fifteen-year-old, but the union was short-lived. So were the rest of his days.

In 1895, Hardin was in El Paso to testify in a murder trial. One day he was standing at the bar shooting dice with a local merchant. John Selman, a man with a grievance— and who the year before had killed the appropriately named Bass Outlaw— came up behind him. Right after Hardin said, “Four sixes to beat, Henry,” Selman shot him in the head. While Hardin was on the floor, Selman shot him three more times in the chest, just to be sure. Enough hometown jurors believed Selman’s ridiculous claim of self- defense in killing Hardin that he was released. He was slain the following year by lawman George Scarborough, who in turn was killed in 1900 while pursuing outlaws in Arizona.

TOM CLAVIN is a #1 New York Times bestselling author and has worked as a newspaper and web site editor, magazine writer, TV and radio commentator, and a reporter for The New York Times. He has received awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, and National Newspaper Association. His books include The Heart of Everything That Is, Halsey’s Typhoon, and Reckless. He lives in Sag Harbor, NY.