by Tom Clavin

Almost all history textbooks and most other sources tell us that the first week of June is the real anniversary of the end of the Civil War. When General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, that was regarded as the official end of the war, but many sources point to almost two months later, on June 2, 1865, because that was the day that General Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of Confederate forces west of the Mississippi River, surrendered his army at Galveston, Texas. But once again, the textbooks leave out the Native American. The very, very last Confederate field general to surrender and thus truly end the Civil War was Stand Watie, a Cherokee.

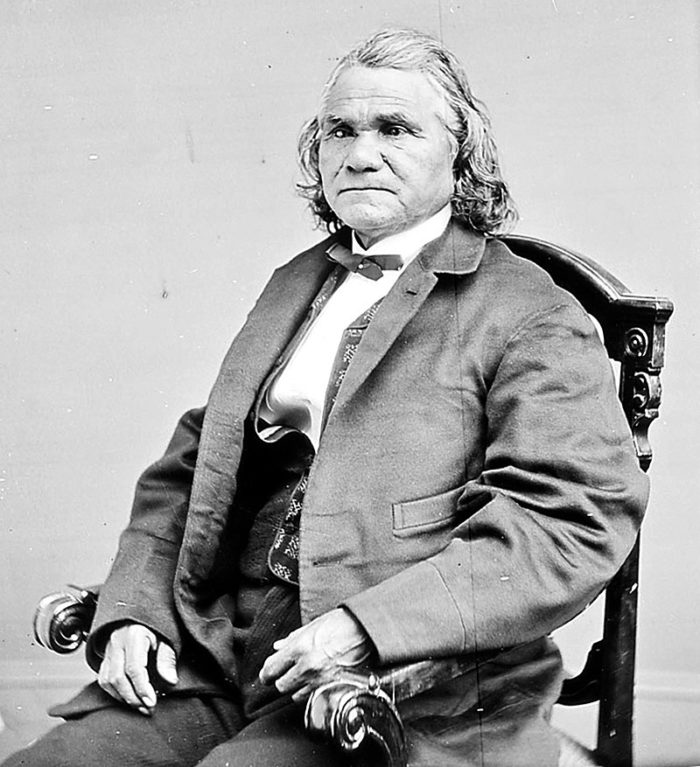

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Standhope Uwatie was born on December 12, 1806, in what is now Calhoun, Georgia, but was then part of the Cherokee Nation. His father was a full-blood Cherokee and his mother was the daughter of a white father and a Cherokee mother. As a young man, he tweaked his name to Stand Watie after converting to Christianity. He started out as a journalist, working for an older brother, Elias Boudinot, who was editor of The Cherokee Phoenix, the first Native American newspaper, which published articles in both English and Cherokee.

Then there was trouble. Watie became involved in the dispute over Georgia’s repressive anti-Indian laws. After gold was discovered on Cherokee lands in northern Georgia, thousands of white settlers arrived. There was continuing conflict, and Congress passed the 1830 Indian Removal Act. It required that all Indians from the Southeast relocate to lands west of the Mississippi River. Two years later, Georgia confiscated most of the Cherokee land, despite federal laws to protect Native Americans from state actions. A defiant Georgia sent militia to destroy the offices and press of The Cherokee Phoenix, which had published articles against Indian Removal. Persuaded that removal was inevitable, Watie and Boudinot were among the men who signed the 1835 Treaty of New Echota. But the majority of the Cherokee still opposed removal and the Tribal Council and Chief John Ross refused to ratify the treaty.

Getting a head start, Watie, who by now had a family, headed to present-day Oklahoma, which was then designated Indian Territory. Those Cherokee who remained on tribal lands in the east were rounded up and forcibly removed by the U.S. government in 1838. Their journey became known as the “Trail of Tears,” which cost the lives of 4,000 Cherokee. Having arrived in the territory earlier, Watie had become a land (and slave) owner and farmer.

Flash-forward to 1861: Ross signed an alliance with the Confederate States to avoid disunity in Indian Territory. In less than a year, Ross and part of the National Council concluded that the agreement had proved disastrous. In the summer of 1862, Ross removed the tribal records to Union-held Kansas and then proceeded to Washington, D.C., to meet with President Lincoln. After Ross did not return, the role of the principal chief was given to Tom Pegg. Following the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, Pegg called a special session of the Cherokee National Council. On February 18, 1863, it passed a resolution to emancipate all slaves within the boundaries of the Cherokee Nation.

Meanwhile, the Confederate-supporting faction of the tribe named Stand Watie as its principal chief. He also became the only Native American to rise to a brigadier-general’s rank during the war. Fearful of the Federal Government and the threat to create a state out of most of what was then the semi-sovereign Indian Territory, a majority of the Cherokee Nation initially voted to support the Confederacy in the Civil War, though less than a tenth of the Cherokee owned slaves. Watie organized a regiment of infantry which became the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles.

Although he fought Union troops, Watie also led his men in fighting between factions of the Cherokee and in attacks on Cherokee civilians and farms as well as against the Creek, Seminole, and others in Indian Territory who chose to support the Union. He is noted for his role in the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas when, under the overall command of General Benjamin McCullough, Watie’s troops captured Union artillery positions and covered the retreat of Confederate forces from the battlefield after the Bluebellies took control.

Over time, however, support for the Confederacy among the Cherokee soldiers declined. Watie continued to lead the remnant of loyal troops. He commanded the First Indian Brigade of the Army of the Trans-Mississippi, which included three battalions of Cherokee, Seminole, and Osage infantry. These troops were based south of the Canadian River and periodically crossed the river to conduct raids in Union territory. They fought in a number of battles and skirmishes in the Indian Territory, Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, and Texas. Watie’s force reportedly fought in more battles west of the Mississippi River than any other unit. He took part in what is considered to be the most famous Confederate victory in Indian Territory, the Second Battle of Cabin Creek on September 19, 1864. Generals Watie and Richard Gano led a raid that captured a Union wagon train and netted approximately $1 million worth of wagons, mules, commissary supplies, and other needed items. Union reports said that Watie’s Indian cavalry “killed all the Negroes they could find,” including wounded men.

The Confederate Army put Watie in command of the Indian Division of Indian Territory in February 1865. By then, however, the Confederates were no longer able to fight in the territory effectively. On June 23, at Doaksville in the Choctaw Nation (also now Oklahoma), three weeks after Gen. Smith surrendered, Gen. Watie signed a cease-fire agreement with Union representatives for his command. Thus, he was the last Confederate general still in the field to surrender, and that, technically if not officially, was the end of the Civil War.

After the war, Watie was a member of the Cherokee delegation to the Southern Treaty Commission, which renegotiated treaties with the United States. From then on, he tried to stay out of politics and rebuild his fortunes. He returned to his farm on Honey Creek, where he died on September 9, 1871. Watie was buried in the old Ridge Cemetery, later called Polson’s Cemetery, as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation.

You know I can’t resist a couple of footnote-like facts: (1) In the Clint Eastwood movie The Outlaw Josie Wales, set after the Civil War, the character of “Lone Watie” was played by Chief Dan George, who was mostly known for the film Little Big Man. (2) On June 13, 2020, following the George Floyd protests, a 1921 monument to Stand Watie and a 1913 monument to Confederate soldiers were removed from the Cherokee Capitol grounds in Tahlequah. The monuments remain in storage.

Tom Clavin is a #1 New York Times bestselling author and has worked as a newspaper editor, magazine writer, TV and radio commentator, and a reporter for The New York Times. He has received awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, and National Newspaper Association. His books include the bestselling Frontier Lawmen trilogy—Wild Bill, Dodge City, and Tombstone—and Blood and Treasure with Bob Drury. He lives in Sag Harbor, NY.