by Diana Schaub

What would possess anyone to produce another book about Abraham Lincoln? Our 16th president is already more written about than any other individual who ever walked the earth, with the sole exception of Jesus (a special case, to be sure).

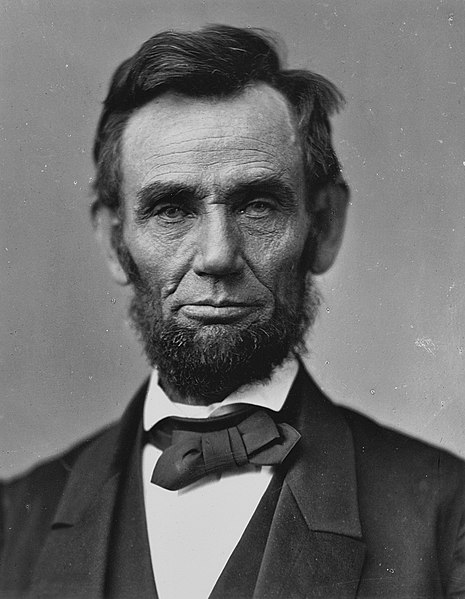

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

I didn’t start as a Lincoln scholar. I began as a student of political philosophy, writing on Montesquieu, the great French thinker who influenced the American Founders. Since I regularly offered a course on American Political Thought, it was natural to include some Lincoln. A little Lincoln soon turned into Lincoln all the time. That is not an unusual response to making his acquaintance. I now conduct a seminar just on Lincoln and shoehorn him into everything else I teach. The more attention one devotes to studying his words and deeds, the more depths are revealed.

His Greatest Speeches tries to fathom those depths by a close reading of three speeches that span Lincoln’s career, from his earliest serious effort to diagnose the political ills of his generation (disregard for law, demagoguery, and hyper-partisan passions) in his 1838 Lyceum Address to his two most notable presidential performances, the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural. By focusing intensely on the grammar, logic, and rhetoric of these carefully crafted works of moral suasion, I believe that new discoveries can be made about how Lincoln moved his audiences and how his words continue to have the same power today.

To illustrate: although the “interest” that some men had in owning and commodifying other men is described as the cause of the war in the third paragraph of the Second Inaugural, the word “slavery” does not appear until the speech reaches its crescendo in its longest sentence—the sentence in which Lincoln presents his God-centered interpretation of the meaning of the Civil War. Simply put, he hypothesizes that the war is the blood price the nation must pay for the sin of “American Slavery” (and he capitalizes the phrase). He does not speak of “southern slavery” or “African slavery,” both of which would have been customary terms. Because the offense of slavery belongs to the nation, “this terrible war” has been meted out “to both North and South.” Lincoln stresses the shared suffering for a shared transgression. Then, through his reference to “the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil,” he traces the offense of American Slavery all the way back to its origin point in the early 17th century. Awareness of the significance of 1619 is not new; 1619 is the featured date in one of the best known and most revered of American speeches.

Lincoln’s theological speculation about the meaning of the war is designed to avert the dangers of postwar vindictiveness on all sides. Northerners were inclined to blame the South for the devastation of the war and to punish the secessionists’ treason; Southerners were inclined to blame the North, refusing still to admit the wrong of slavery and determined to oppose the advent of racial equality. Presumably, the newly freed population, while welcoming release from bondage, might be inclined toward vengeance for those long centuries under the lash of oppression. Lincoln’s spiritualized account of the war helps all parties rise above their worst passions, thus opening the way toward sectional reconciliation and racial justice. If all citizens could join in understanding the war along the lines Lincoln articulates, then the space would be cleared for human charity, or at least a lessening of malice.

Early in the speech, when he might have referred to “slavery,” Lincoln instead refers to those who were under its yoke, stating “One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it.” He highlights various features of this portion of the population: the number, the color, the condition, and the location of these residents are each important, but perhaps most important is simply the description of these persons as belonging to the whole. Lincoln focuses on enslaved persons as real human beings who, because they were not at liberty, had no say in their location; they were “distributed” rather than having chosen to live or reside somewhere. Note also that Lincoln does not speak of the South, but rather “the Southern part” of the Union. Over the course of the war, it might have been easy to slip into regarding the North as synonymous with the Union; Lincoln rejects that identification. The Union is the whole and the inhabitants of this “Southern part”—regardless of color or former condition—are parts of the whole. His language attempts to put a badly fractured whole together in a new, more coherent, and compatible way. Every word is chosen to help achieve the just and lasting peace to which Lincoln directs the American people in his final paragraph.

It’s humbling to realize that this post is already three times the length of the Gettysburg Address and slightly longer than the Second Inaugural. As the master of profound brevity, Abraham Lincoln might well have excelled at social media—though he would have used his posts and tweets for purposes of Union rather than angry division.

Diana Schaub is Professor of Political Science at Loyola University Maryland and a Visiting Scholar at AEI. She was a member of the President’s Council on Bioethics from 2004-2009. A recipient of the Richard M. Weaver Prize for Scholarly Letters, she is the author of Erotic Liberalism, contributing editor of The New Atlantis, and part of the National Affairs publication committee. She has written for The Claremont Review of Books, City Journal, The New Criterion, and Commentary, among others.