by Chris DeRose

In the Battle of Athens, Tennessee, returning veterans of WWII took up arms one last time against a corrupt political machine. To understand why they would risk their liberty and their livesagainst a superior force with all the odds against themwe need to see what they survived and what they came home to.

FRIDAY, AUGUST 7, 1942

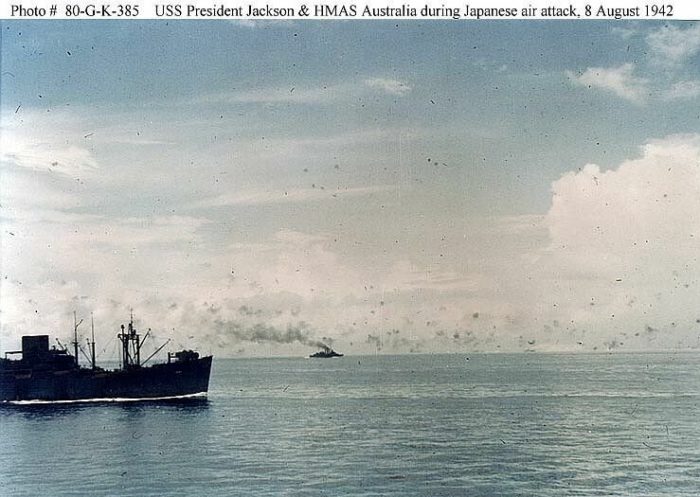

3:00 a.m.USS Jackson, Solomon Islands

Bill White and the marines of Company B scrambled down nets toward the Higgins boats that would take them to Florida Island. They ran through the foam, onto the beaches, the first Americans of the war to land in hostile territory.

Their eyes darted across the jungle. The breeze blew the tall trees and grass. But there were no signs of the enemy. They passed through small villages. Abandoned. They charged the bluffs and found nothing at the top.

“We’ve been duped,” someone said. Tricked, they were sure, by other marines who wanted all the fighting for themselves.

“What the hell is this, another training exercise?” yelled one marine.

News crackled over the radio as marines cursed the empty island. The marines who had landed on Gavutu were being slaughtered. They ran back to the boats as fast as they could.

Bill had been told that the Japanese weren’t very good fighters. It didn’t look that way on Gavutu. Nearly all the paratroopers were dead. Some shot between the eyes.

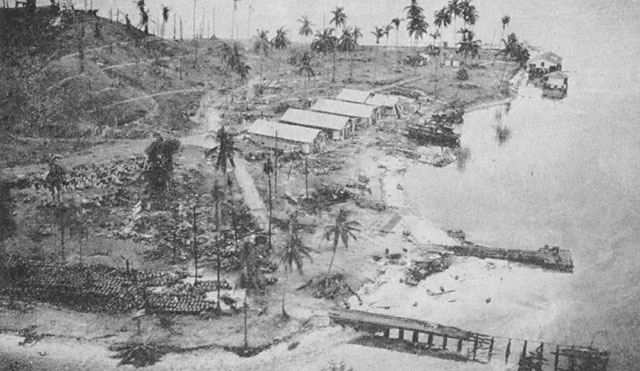

The added firepower brought by Bill and Company B nearly cleared Gavutu of the Japanese. But snipers kept taking shots at them from the nearby island of Tanambogo. The commanders assumed there were around fifteen, who could be dealt with relatively easily. It was decided that Bill’s company would make an amphibious landing on Tanambogo, eliminate the snipers, and reinforce the final push on Gavutu.

At 6:00 p.m., navy shells fired over the Higgins boats onto Tanambogo. One fell short, wounding an American coxswain and sending his boat in the wrong direction. Other ships unwittingly followed.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

The three boats that made it to Tanambogo encountered a wall of flames stretching fifty feet out to sea. The Japanese had doused the beach and water with gasoline. Some of the boats caught on fire. The Japanese opened up with machine guns. Bill returned fire using the motor of his Higgins boat as cover. The machine gunner at the front of Bill’s boat was shot and “bounced back dead.” Another marine took his place and was killed within seconds. The front of Bill’s boat burst into flames. Bill jumped out into the water and tried to get to the beach.

Marines who had jumped or fallen from the burning boats and made it to shore were stabbed with Japanese sabers and thrown alive into the beach bonfire. The air was filled with the sounds of gunfire and screaming marines.

The marines retreated to the boats, to Gavutu, where they would pass an uneasy night under the threat of death from Japanese soldiers and the unbowed snipers of Tanambogo.

It was their first day of war.

Bill White had enlisted days after Pearl Harbor and returned home for the first time in three years to bury his grandfather. Four sheriff’s deputies wearing gold badges and guns were there to meet his bus. They arrested a group of Bill’s fellow passengers, still wearing their uniforms, for public drunkenness. They’d had a few beers to celebrate being alive, but far from enough to intoxicate a navy sailor.

“What’s going on?” Bill asked a bystander.

“Those deputies meet every bus and every train, and if you’re drinking a beer or anything they’re arresting you and making you pay a fine.”

Bill couldn’t believe it. These boys had risked their lives. And now they were headed to jail and about to lose their mustering out pay to a bunch of thugs. “Hellfire,” Bill said.

At night in his boyhood room he could hear the screams of the marines on Tanambogo beach. Bill had longed for his bed, but after so many nights on the ground he couldn’t get comfortable. He slept on the floor.

Edd, his father, asked Bill to head to the rationing board to get gasoline stamps for the drive to the funeral. Bill walked to the Fisher Building, where Robert Fisher, president of the local rationing board and owner of a hosiery mill, sat behind the desk that had been his duty station during the war.

Bill asked for five gallons of gas.

No, said Fisher. “Don’t you know there’s a war going on?” Bill considered a number of responses, none of which would get him closer to his grandpa’s funeral. He gave Fisher a look: “Well, I just want five gallons.”

“You can’t have it.”

“Alright,” Bill said. “That’s alright.”

Leaving the Fisher Building he saw a friend on the street. He told him that he needed gas, but “ration boy wouldn’t let me have it.”

“Well that’s easy, Bill,” said his friend. “There stands the chief of police,” he said, pointing. “Give him five dollars and he’ll give it to you.”

Bill ordered ten gallons, twice as much as he needed, rather than risk this humiliation a second time. He watched as the police chief calmly counted out his stamps and put Bill’s money directly in his pocket.

Bill told his father the story when he came home. His father, it turned out, had a story for him, one that had happened while Bill was away.

Edd White was proud and quiet, a cavalryman of the First World War. He walked five miles a day to work at the power station on Railroad Avenue. He carried his lunch in a brown paper bag and a pint of milk from Mayfield’s Dairy. While walking past the jail on his way home he saw four deputies stare at him, get in a car, and start the engine. As he walked past the courthouse, the car was in the middle of the street, following him. He lowered his head and kept walking. He walked past the bus station and they were right alongside him. Edd picked up the pace. They accelerated. He didn’t know what they wanted with him or why. But he knew it wasn’t good. He panicked and started running to his house. The car pulled in front of him and slammed on its brakes. Four deputies jumped out with clubs in their hands. He was arrested and taken to jail. Now it was time to figure out a reason. The deputies took his milk bottle out of the bag and passed it around, taking a sniff. “Smells funny,” they agreed. The deputies who protected the roadhouses and honkytonks and lined their pockets with kickbacks from bootleggers and pimps decided the remnant of Edd White’s milk was alcohol. He was fined $16.05, several days’ pay.

The situation back home had been “a big surprise” to Bill. “I had plenty of worries over there,” Bill said. Now he was home, and “everything, everything, everything you’ve been told you’re supposed to be fighting for wasn’t there.”

Something was going to have to give. The veterans began secretly planning to challenge the machine at the next election. When the machine refused to give them a fair election, the stage was set for one last battle, and the only successful rebellion on US soil since the Revolution.

Chris DeRose is the New York Times Bestselling Author of Founding Rivals: Madison vs. Monroe, the Bill of Rights, and the Election that Saved a Nation, and The Presidents’ War: Six American Presidents and the Civil War That Divided Them. He was formerly Senior Litigation Counsel to the Arizona Attorney General, a Professor of Constitutional and International Law, and Clerk of the Superior Court, where he led a team of 700 in serving America’s fourth largest county.