by Susan Eisenhower

Few people have made decisions as momentous as Eisenhower, nor has one person had to make such a varied range of them. From D-Day to the Red Scare to the Missile Gap controversies, Ike was able to give our country eight years of peace and prosperity by relying on a core set of principles. Susan Eisenhower’s How Ike Led shows us not just what a great American did, but why—and what we can learn from him today. Read on for an excerpt.

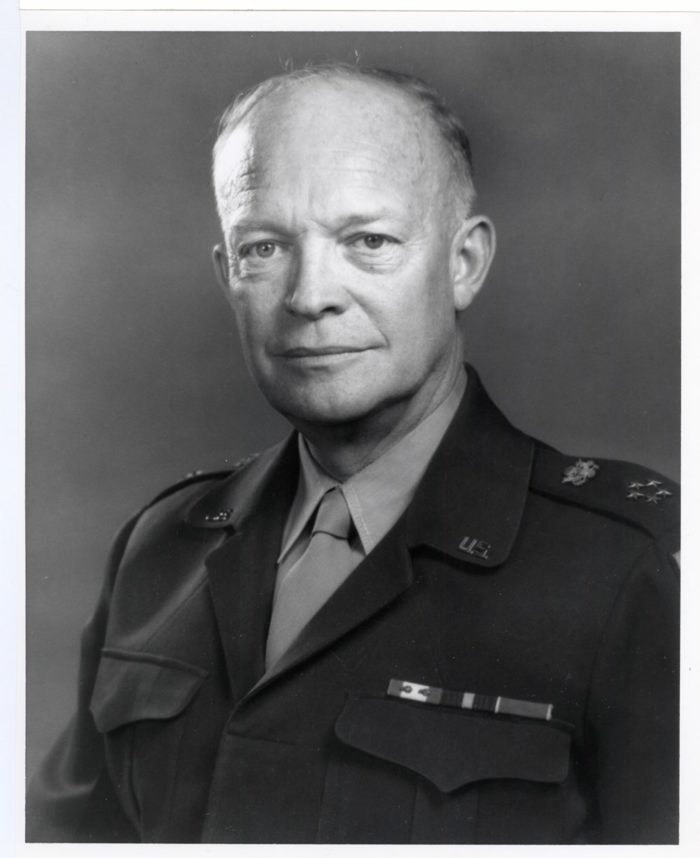

June 5, 1944. (U.S. Army)

On July 11, 1944, Dwight Eisenhower’s naval aide, Capt. Harry Butcher, asked his boss, supreme commander of Allied Forces Europe, if he could keep the note that Ike had carried in his wallet on D-day. Operation Overlord was the mightiest amphibious military operation in history, and a turning point of World War II. Eisenhower was uncomfortable about relinquishing the short statement, and he did not understand why Butcher wanted it. Ike had written such a note, he told the captain, for every major military operation for which he had responsibility.

It read:

Our landings in Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.

July 5.

Ike thought so little of the historical significance of his simple “in case of failure” communiqué that when Butcher asked him to date it, he wrote “July 5,” thinking only of the current month—rather than June 5 when Allied forces were poised to storm the Normandy coast.

This unused communiqué is often thought of today as a symbol of Ike’s leadership—the willingness to take full and complete responsibility for his decisions—even though one of the most important variables, in this case the weather, was out of his control. It is correct that Eisenhower would have released the statement had the invasion forces been thrown back into the sea; but they weren’t and Ike wanted to keep the note private. As he had told Butcher in 1942, when his naval aide began his duties as the headquarters diarist, there should be no effort to apply PR spin to things. “We are not operating or writing for the record,” Ike had told him. “[We are here] to win the war.”

Eisenhower wrote such “communiqués” as much for himself as for any kind of public release, should the worst happen. He was not trying to burnish his reputation in writing it, he was reminding himself, and if necessary others, that he alone was responsible for the outcome of the mission. It was a personal and public form of accountability.

Much has been written about D-day and the vast undertaking aimed at the heart of Nazi German power. It is worth remembering that the Germans saw this endeavor as the existential moment of the war. The German High Command knew full well that the outcome of the war rested on making sure the Allies failed in any amphibious assault—for behind any successful beachhead lay the nearly unlimited military and industrial resources of the United States.

Before the fateful assault known as Operation Overlord, or D-day as we call it, General Eisenhower was called upon to make an array of difficult decisions. Many of them would be life-or-death calls; all would have lasting impact on the continent of Europe and across the United States.

In addition to the frightening uncertainties of the Normandy weather in launching any attack, General Eisenhower had to make a number of consequential calls, from the role of tactical and strategic bombing and their likely targets, to the resolution of various issues related to Allied squabbling and doubts about the mission.

Ike later wrote in his diary that on June 6:

There was no universal confidence in a completely successful outcome. Indeed, most people thought that even should we, in some two or three years eventually win, we would pay a ghastly price in battling our way toward Germany…Some newspapers went so far as to predict 90 percent losses on the beaches themselves. Even Winston Churchill, normally a fairly optimistic individual, never hesitated to voice his forebodings about the venture.

The assault on Normandy from across the English Channel, and the subsequent battles for France and Western Europe, were complex operations in which military strategy fused with geopolitical considerations. Since 1942, the Americans, most notably Gen. George C. Marshall—chief of staff of the army—argued for this direct approach. Eisenhower, too, favored it. The British, however, with the Dunkirk evacuation and the failed Dieppe raid still fresh in their minds, were skeptical, if not downright hostile to the idea.

There were a number of strategic considerations on both sides. But perhaps one of the most compelling arguments for mounting a direct assault, sooner rather than later, had rested on our eastern ally, the Soviet Union, and its attitude to the opening of a second front. The upper echelons of decision-makers in the American war effort argued that there was a danger that the Soviet Union might make a separate peace with Hitler, not unlike World War I when the Russians withdrew from their alliance with Britain and the United States, to significant effect. No doubt this was a key factor when President Franklin Roosevelt promised Soviet leader Joseph Stalin that the Allies would open a second front that would include the Normandy landings and Operation Anvil, an invasion of southern France that would augment D-day and post-D-day forces. In return Stalin agreed to open an offensive on the eastern front, in support of our assault, to assure that the Germans could not relocate their forces to the West.

© Copyright Susan Eisenhower 2020

Susan Eisenhower, one of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s four grandchildren, is a consultant, author, and a Washington, DC-based policy strategist with many decades of work on national security issues. She lectures widely on such topics, including strategic leadership.