by Keith Lowe

The Second World War was not just another crisis—it directly affected more people than any other conflict in history. Over 100 million men and women were mobilized, a figure that easily dwarfs the number who fought in any previous war, including the Great War of 1914–18. Hundreds of millions of civilians around the world were also dragged into the conflict—not only as refugees like Georgina Sand (a Jewish child survivor), but also as factory workers, as suppliers of food or fuel, as providers of comfort and entertainment, as prisoners, as slave labourers, and as targets. For the first time in modern history the number of civilians killed vastly outweighed the number of soldiers, not just by millions, but by tens of millions. Four times as many people were killed in the Second World War as in the First. For every one of those people there were dozens who were indirectly affected by the vast economic and psychological upheavals that accompanied the war.

As the world struggled to recover in 1945 entire societies were transformed. The landscapes that rose from the rubble of the battlefield looked nothing like the landscapes that had existed before. Cities changed their names, economies changed their currencies, people changed their nationalities. Communities that had been homogeneous for centuries were suddenly inundated with strangers of all nationalities, all races, and all colors—people like Georgina, who didn’t belong. Entire nations were set free, or newly enslaved. Empires fell and were replaced with new ones, equally glorious and equally cruel.

The universal desire to find an antidote to war spawned an unprecedented rush of new ideas and innovations. Scientists dreamed of using new technologies—many of them created during the war—to make the world a better, safer place. Architects dreamed of building new cities out of the rubble of the old, with better housing, brighter public spaces and more contented populations. Politicians, economists and philosophers fantasized about egalitarian societies, centrally planned and efficiently run for the happiness of all. New political parties, and new moral movements, sprang up everywhere. Some of these changes built on ideas that had come about as a result of earlier upheavals, such as the First World War or the Russian Revolution, and some of them were entirely new; but even the older ideas were adopted after 1945 with a speed and an urgency that would have been unthinkable at any other time. The overwhelming nature of the war, its uniquely horrific violence and its unparalleled geographical scope, had created a thirst for change that was more universal than at any other time in history.

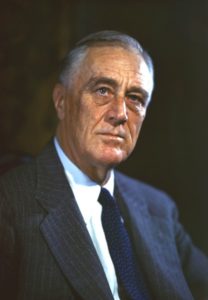

The word that came to everyone’s lips was ‘freedom’. America’s wartime leader, Franklin D. Roosevelt, had spoken of four freedoms – freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want and freedom from fear. The Atlantic Charter, drawn up in consultation with the British prime minister, Winston Churchill, had also spoken of the freedom of all peoples to choose their own form of government. Communists spoke of freedom from exploitation while economists spoke of free trade and free markets. And in the wake of the war, some of the world’s most influential philosophers and psychologists wrote of even deeper freedoms, fundamental to the human condition.

The call was taken up all over the world, even in those countries far removed from the fighting. As early as 1942 the future Nigerian statesman Kingsley Ozumba Mbadiwe was demanding that liberty and justice be extended to the colonial world once the war was won. ‘Africa,’ he wrote, ‘will accept no other prize than freedom.’ Some of the most enthusiastic founder members of the United Nations were the Central and South American countries, who envisaged an international system that would see ‘injustice and poverty banished from the world’, and a new era in which ‘all nations, large and small’, would ‘cooperate as equals’. The winds of change were blowing everywhere.

According to the American statesman Wendell Willkie, the atmosphere during the Second World War was far more revolutionary than it had been during the First. After touring the globe in 1942, he returned to Washington inspired by the way that men and women all over the world were struggling to throw off imperialism, reclaim their human and civil rights and build ‘a new society . . . invigorated by independence and freedom’. It was, he said, enormously exciting, because people everywhere seemed to have a new-found confidence ‘that with freedom they can achieve anything’. But he also confessed that he found this atmosphere more than a little frightening. No one seemed able to agree on a common goal. If they did not do so before the war was over, Willkie predicted a collapse of the spirit of cooperation that was holding the Allies together, and a return to the same discontents that had led to war in the first place.

According to the American statesman Wendell Willkie, the atmosphere during the Second World War was far more revolutionary than it had been during the First. After touring the globe in 1942, he returned to Washington inspired by the way that men and women all over the world were struggling to throw off imperialism, reclaim their human and civil rights and build ‘a new society . . . invigorated by independence and freedom’. It was, he said, enormously exciting, because people everywhere seemed to have a new-found confidence ‘that with freedom they can achieve anything’. But he also confessed that he found this atmosphere more than a little frightening. No one seemed able to agree on a common goal. If they did not do so before the war was over, Willkie predicted a collapse of the spirit of cooperation that was holding the Allies together, and a return to the same discontents that had led to war in the first place.

Thus the Second World War sowed the seeds not only of a new freedom, but also of a new fear. As soon as the war was over people began to eye their former allies with distrust once again. Tension returned between the European powers and their colonies, between right and left and, most importantly, between the USA and the Soviet Union. Having only recently witnessed an unprecedented global catastrophe, people everywhere began to worry that a new, even bigger war was coming. The ‘undercurrent of unease’ described by Georgina Sand was a universal phenomenon after 1945.

In this respect, Georgina’s story in the immediate aftermath of the war is perhaps also emblematic. After peace was declared she returned to Prague in the hope of finding the sense of belonging she had lost as a child; but when she did not find it, she hoped instead that she could create it anew. She met Walter again, whom she had known as a girl, and fell in love. She got married, made friends, prepared to settle down. With all the optimism of youth, she imagined that her future could only be bright, despite the obstinate shadow that the war was still casting over her life. Even after discovering the death of her mother she truly believed that she would be able to put the misery of the war years behind her, because she wanted to move on, to reinvent herself. She wanted to be free.

Unfortunately the Czech authorities had different ideas. In 1948, when the Communists seized control, she and Walter were instructed to pledge their unquestioning loyalty to the new regime, and by extension to the Soviet superpower. Since they were not prepared to do so, they were forced to flee the country once again. Their flight was symbolic of yet another consequence of the Second World War – the new Cold War, which saw the whole world polarized between West and East and between right and left. To use Churchill’s phrase, an iron curtain was drawn across the centre of Europe; revolutions, coups and civil wars broke out across the developing world. More refugees, more stories.

KEITH LOWE is the author of the critically-acclaimed Inferno: The Devastation of Hamburg 1943, and Savage Continent, an international bestseller and the winner of both the Hessell-Tiltman Prize for History (2013), and Italy’s prestigious Cherasco History Prize (2015). He lectures on both sides of the Atlantic, appears on TV and radio in Europe and the US, and writes for a variety of magazines and newspapers around the world. He lives in north London with his wife and children.