by Frank McDonough

In the following excerpt from The Hitler Years: Triumph, 1933-1939, Frank McDonough discusses the political environment in Germany in 1933 as Adolf Hitler sets his plans in motion to become Germany’s next Chancellor.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Germany license.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H1216-0500-002 / CC-BY-SA

It was icy cold in Munich on New Year’s Day. Adolf Hitler was drinking coffee over breakfast at his luxurious apartment at 16 Prinzregentenplatz. The morning papers made gloomy reading about his political prospects in the coming year. A critical article in the social democratic newspaper Vorwärts headlined ‘Hitler’s Rise and Fall’ suggested the Nazi Party’s electoral popularity had peaked in the July 1932 federal election. The Berliner Tageblatt mockingly observed: ‘Everywhere in the world people were talking about – what was his name: Adalbert Hitler. Later? He’s vanished!’ The official Nazi Party newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter, printed Hitler’s ‘Battle Message for 1933’ in which he refused to compromise his principles for ‘a couple of ministerial posts’, and promised to continue his ‘all or nothing strategy’ of remaining in opposition until he was offered the post of Chancellor.

During the evening of 1 January Hitler attended a performance of Richard Wagner’s comedic opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Master-Singers of Nuremberg) at Munich’s Court Theatre. Accompanying him were his deferential personal assistant Rudolf Hess, his photographer Heinrich Hoffmann, and Eva Braun. Hoffmann had ‘a weakness for drinking parties and hearty jokes’. Braun, tall, blond and strikingly attractive, was an assistant in Hoffmann’s photography studio. This is where she first met Hitler when she was just seventeen. She had slowly emerged as Hitler’s primary female companion after the tragic and somewhat suspicious death of his half-niece Geli Raubal, whose corpse had been found in Hitler’s apartment on 18 September 1931. The inquest concluded that she had shot herself through the heart, using Hitler’s own pistol. Braun’s employment by Hoffmann meant that she could accompany Hitler socially without arousing public suspicion of any romantic involvement between them.

After the performance, they all went to a party at the opulent Munich residence of Hitler’s witty and wealthy friend Ernst ‘Putzi’ Hanfstaengl, a Harvard graduate who joined the Party in the early 1920s. Hitler was in a very optimistic mood that night, Putzi later recalled. After criticizing the talented young conductor Hans Knappertsbusch’s handling of Wagner’s opera, Hitler turned to Putzi and said: ‘This year belongs to us. I will guarantee that to you in writing.’

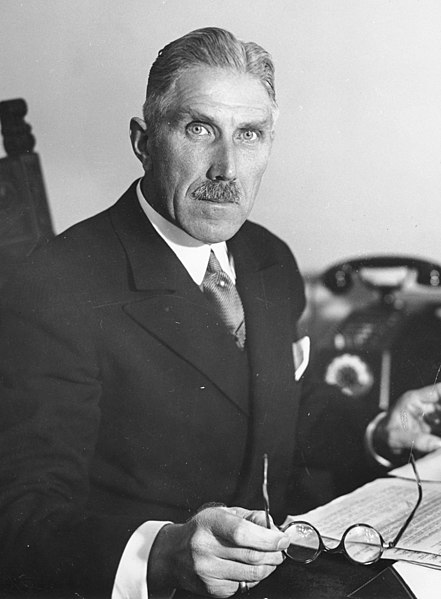

At the start of 1933 democratic government in Germany had virtually collapsed. The previous year had seen three different German chancellors: Heinrich Brüning, Franz von Papen and General Kurt von Schleicher, and two inconclusive national elections in July and November. Each Chancellor failed to establish a government that could command a majority in the German parliament, known as the Reichstag. Papen’s government fell after a vote of no confidence, losing by 512 votes to 42. He was replaced by Schleicher, who took office on 3 December 1932. Schleicher was appointed by Germany’s 85-year-old President Paul von Hindenburg using the arbitrary power granted to him under Article 48 of the flawed Weimar constitution. This allowed him to appoint not merely the German Chancellor, but also the other members of the cabinet. As a result, the democratically elected members of the Reichstag were sidelined in the decision-making process. Hindenburg wanted to establish a stable and popular right-wing authoritarian government, excluding all left-wing parties, but since 1930 he had failed to make this a reality.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Germany license.

Attribution: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1988-0113-500 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Schleicher had only a few weeks to put together a coalition government that could survive a potential vote of no confidence in the Reichstag. He envisaged an authoritarian regime which would appeal to the working classes, but this was completely out of step with what Hindenburg wanted. Schleicher spent most of December 1932 trying to persuade Gregor Strasser – a high-profile figure on the socialist left of the Nazi Party – to join his cabinet, with the aim of splitting the Nazi Party. On 3 December he offered Strasser the posts of Vice Chancellor and Minister-President of Prussia, but Strasser refused both offers. Strasser resigned from the Nazi Party on 8 December, claiming that he could no longer accept Hitler’s uncompromising refusal to become the Chancellor of a coalition government. In his diary Joseph Goebbels, the leading Nazi propagandist, summed up Gregor Strasser’s predicament in two words: ‘Dead man!’

Franz von Papen, who had not forgiven Schleicher for helping to bring down his own government, wanted to return to power, but he realized that in order to create a viable coalition he needed the cooperation of Adolf Hitler. As the leader of the most electorally popular political party Hitler’s claim to be Germany’s Chancellor was very strong, but he still needed help to get into power.

Copyright © 2021 by Frank McDonough

Professor Frank McDonough is an internationally renowned expert on the Third Reich and has written many critically acclaimed books on the topic. He studied history at Balliol College, Oxford, and gained a Ph.D. from Lancaster University. He has appeared on TV and radio numerous times and was featured in a six-part series, Nazi Secrets, for National Geographic in 2012 and a ten-part series, The Rise of the Nazi Party, for the Discovery Channel in 2014. The History Network placed McDonough’s Twitter account, @FXMC1957, in the Top 30 Most Popular Historical Twitter Accounts in the World.