by Bradley W. Hart

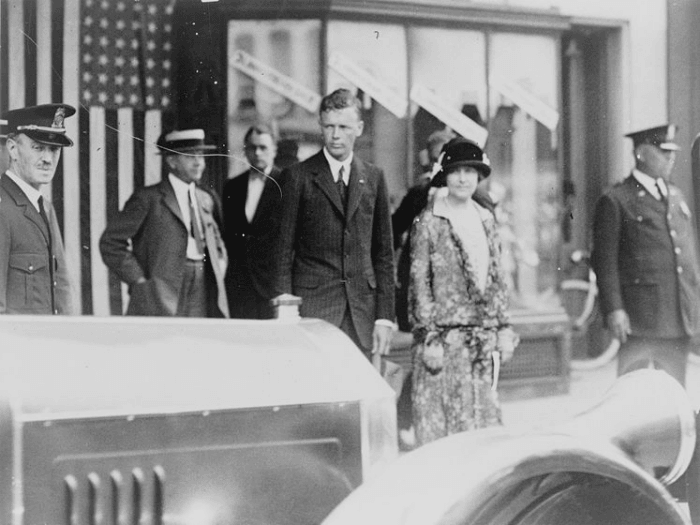

On September 11, 1941, one of America’s most famous celebrities took to a stage before a raucous crowd in Des Moines, Iowa.

This was famed aviator Charles Lindbergh—nicknamed Lucky Lindy—addressing a crowd of America First supporters three months before Pearl Harbor. For months, Lindbergh had been traveling the country giving similar speeches opposing U.S. entry into the war in Europe. Tonight’s speech was different, though. There were, he told the crowd that evening, three groups that had conspired to draw the country into the conflict: “the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt Administration.” Together, he continued, these groups had executed a plan to draw the country into war gradually by building up its military and then manufacturing a series of “incidents” to “force us into the actual conflict.”

Lindbergh poured particular ire on the Jews. “Jewish groups in this country,” he told the crowd, should realize that in the event of war “they will be among the first to feel its consequences.” Individual Jews, he concluded, presented a unique danger to the United States because of their “large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our Government.” Despite the alleged machinations of these groups, Lindberg reserved hope that they might cease their efforts to push the U.S. toward war. If that could be managed, he said, “I believe there will be little danger of our involvement.”

Lindbergh’s address that night created a huge national controversy. It was covered on Page 2 of the New York Times and in most of the country’s major papers. Letters poured into newsrooms and America First headquarters both supporting and denouncing Lucky Lindy. Even Franklin Roosevelt’s press secretary weighed in and compared the remarks to recent statements coming from Berlin. In just a few minutes on stage, Lindbergh damaged his reputation to a degree from which it would never recover.

But what had taken a once-beloved American hero to these depths? Why did one of the country’s most popular celebrities endorse anti-Semitism and become one of Hitler’s key American friends? To understand Lindbergh’s remarks on that Iowa night, we have to look at who he truly was, and the company he kept in the critical years before 1941. The answers to those questions, as we will see, are troubling.

Lindbergh leapt into the public consciousness in 1927, when he became the first man to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. This was not only a major feat in aviation history, but also captured the public’s imagination in a period when technology was rapidly changing the world. Lindbergh returned home from Europe as one of the most famous people in the world. In 1932, the disappearance of Lindbergh’s son from his home in New Jersey—and the subsequent discovery of the child’s body—became the crime story of the century and led to a huge outpouring of grief. After the resulting trial ended, Lindbergh and his wife Anne left the United States for Europe to escape the media attention that followed them everywhere. Their time in Europe, however, would prove to be an important turning point.

In June 1936, Lindbergh was living in Britain and received a letter from Major Truman Smith, the American Military Attaché in Berlin. Smith wanted to know whether the aviator would be willing to visit the country and produce a report for the U.S. government about recent developments in German aviation. Smith’s proposal for the visit was approved in advance by Luftwaffe head Hermann Göring, who was no doubt eager to reap the publicity benefits of a visit by the world’s most famous aviator. The visit took place in July 1936 and included trips to airfields, aircraft factories, and research facilities. There were social functions as well, including a luncheon packed with government officials in which Lindbergh delivered a lengthy speech on the destructive potential of aerial bombardment. Lindbergh and his wife later paid a social call to Göring, who introduced them to his pet lion Augie. Lindbergh’s final major stop was a visit to the opening ceremonies of the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, where he and Anne sat near Adolf Hitler but evidently did not speak to him.

Continue reading Hitler’s American Friends: Charles Lindbergh and ‘America First’ on the Unknown History channel at Quick and Dirty Tips. Or listen to the full episode below.