by Kevin R. C. Gutzman

The Jeffersonians chronicles the lives, policy initiatives, and critical decisions of three visionary Virginian presidents—Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe. In the following excerpt, author Kevin R. C. Gutzman discusses Thomas Jefferson’s views on slavery and the broader push for abolition in post-revolution America.

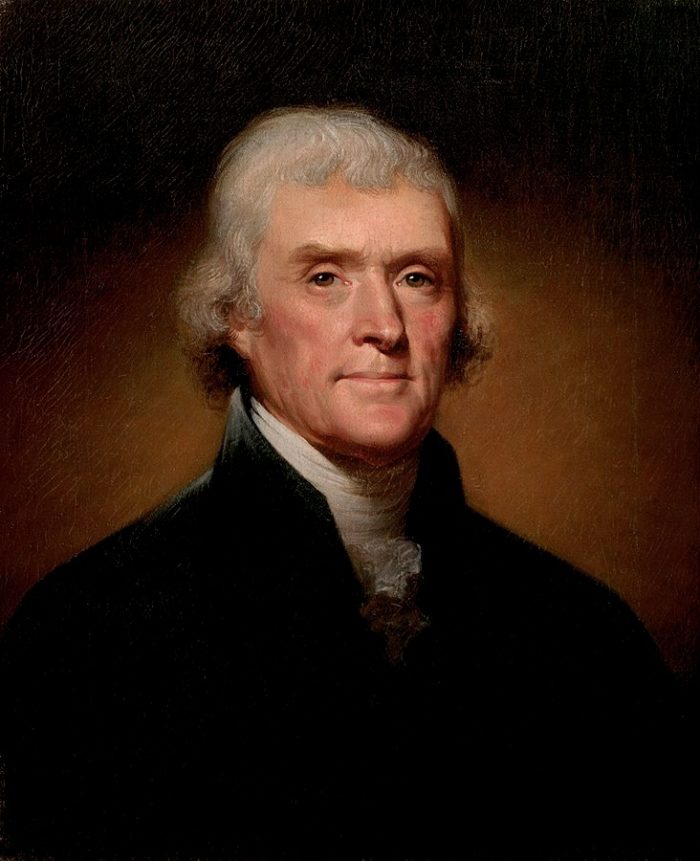

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

The federal Union over which Thomas Jefferson became president on March 4, 1801, was a land of hope and promise. Its southern boundary was at Spanish Florida, which in those days extended all the way to the Mississippi River. Though John Jay’s diplomatic triumph at Paris in 1783 had unexpectedly given Americans the Father of Rivers as their western border, the pivotal ocean outlet at New Orleans remained the property of the Spanish monarchy—a hesitant participant on the American side in the Revolution.

The Electoral College in which Jefferson had tied Burr and the House of Representatives that chose between them represented the original thirteen states, plus Tennessee, Kentucky, and Vermont. Communication between the coastal United States and the areas beyond the Appalachians was slow, because roads were virtually nonexistent. From Bacon’s Rebellion (1676) through the Carolina Regulation of the 1760s–1770s, Shays’s Rebellion (1786), and the ratification campaign (1787–88) to the Whiskey Rebellion (1794) and on, East-West relationships had always been fraught. Inlanders believed their coastal brethren disdained, ignored, or exploited them, depending on the circumstance.

Besides distinctions between the coastal regions and the trans-Appalachian area, different parts of America also differed in other ways. So, for example, the longest-settled American region, the Tidewater Chesapeake, had come, through a combination of factors, to be almost entirely rural. Its economy centered on production of tobacco for export using slave labor, and numerous Tidewater counties had substantial slave majorities—several of two-thirds or more.

Tobacco planters dominated Virginia politics and society. Some of the great families, the fabled “FFVs” (First Families of Virginia), had large networks of kin owning tens of thousands of acres in numerous counties in Tidewater, Southside Virginia (the region below the James River, which bisects the Tidewater from west to east), and the Piedmont. Jefferson and Madison, respectively of the Randolph and the Taylor clans, hailed from Piedmont, Virginia. “Keep your land and your land will keep you,” John Randolph of Roanoke, a cousin of Jefferson’s prominent in Virginia Dynasty politics, remembered having his mother counsel him. Randolph followed that advice to a T. His slaves took care of him too, and he requited them by freeing more than four hundred of them at his death. (Neither Jefferson nor Madison, far less careful with their money, did anything like that.)

A notably wealthy Virginian owned dozens of slaves. Madison owned more than a hundred. Jefferson owned more than two hundred at the height of his holdings. Both Madison and Jefferson expressed considerable uneasiness about this. Hard though it is for us to believe now, they were born into a world in which essentially no one had ever said slavery was wrong. Yet they grew to think it was as other citizens of the transatlantic “republic of letters” did. Besides Jefferson’s cousin Randolph, George Washington freed his many slaves in his will. Large planters such as they were few and far between. Jefferson wrote that slavery was an evil that had to be, would be, abolished. He took substantial steps against it, as we will see. Yet he died enmeshed in slaveholding, and nearly all of his slaves were auctioned to satisfy his creditors. Madison’s story was similar.

When Jefferson became president, tobacco remained a lucrative crop. Some great planters such as George Washington had begun the process of giving up growing John Rolfe’s weed and transitioning to wheat. Virginia became a slave exporter, peopling Deep South states with bondsmen for money. John Randolph, for one, decried this practice. Being sold away from everything and everyone they knew was a terrible fate for slaves. Yet the practice continued. Though the most populous British colony in North America, Virginia by 1776 had no significant town. At the time of Jefferson’s inauguration a quarter century later, it still had none.

From 1619 Virginia representatives met in its General Assembly, and they became a separate House of Burgesses in 1642. It was the first representative assembly in the Western Hemisphere. Planters—owners of significant numbers of slaves—dominated it from the first. In 1619 large landowners in Virginia employed mostly indentured servants, the overwhelming majority of whom were white. That changed in the 1680s, when improvements in the English economy and the Royal Navy’s success in the Atlantic made white labor less readily available and slaves cheaper than before. The property qualification for voting seems to have been low enough that about half of white men qualified—which meant Virginia had a more democratic system than virtually any other place in the world, the New England colonies and a couple of Swiss cantons excepted.

New England, the second part of English North America settled, never had significant slave-based agriculture. Puritans and Separatists had no particular moral qualms about slavery, but the environment of Massachusetts was not conducive to it. With its scant arable land, harsh weather, and lengthy shorelines, and because New England’s first settlers arrived as family units, New England early on came to be a land of small farms, sailing ships, and towns. Neither a very rich class nor a subordinated laboring class was much in evidence. The social elite ran town meetings, in which all male members of the local congregation were eligible to participate. Anyone who ran athwart the religious authorities would be shown the road to Rhode Island, the Isle of Errors. Quakers who returned after being expelled from Massachusetts Bay Colony suffered the draconian punishment of hanging, which prompted King Charles II to merge Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay into one colony, New Haven and Connecticut into another, and to ban such behavior. He also took control of selecting Massachusetts’s governor and required the New England colonies to allow construction of Anglican churches.

Between New England and Maryland lay the Middle Colonies, three of which had been founded by Quakers (and thus never had a religious establishment) and the other of which, New York, was peculiar from the beginning. A Dutch colony, New Amsterdam proved too attractive a property not to draw England’s attention. When the English conquered it, naming it for James, Duke of York (later James II/VII), English settlement meant it never had any significant religious majority. Nominally Anglican in the area around the city, its heterogeneous population meant New York never really required church participation. All four of the Middle Colonies’ cultures centered on trade, particularly through the great ports of New York and Philadelphia. One significant distinction between the Quaker colonies and New York lay in the affectation of simplicity among the well-to-do Quakers. New York’s rich always gloried in their riches. By the time the Revolution came, the Hudson River Valley and counties on Long Island featured significant slaveholdings, but after the war, the slave owners’ political power did not match their economic majesty.

At the Revolution’s start colonists began to take up in earnest the question of slavery’s future. Essentially unchallenged, if not unremarked, through world history, slavery came to seem a moral error among a few Anglophones late in the seventeenth century. Pennsylvania colonists organized the first abolition organization, the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, in Philadelphia in 1775. They elected sometime governor Benjamin Franklin its president in 1785, then asked him to present its cause to the Philadelphia Convention that wrote the Constitution. Though a member, Franklin seemingly did not present the abolitionist cause. He did, however, join in petitioning the First Federal Congress for abolition in 1790. By that time numerous states had acted against slavery—Vermont and Massachusetts by banning it, and several others by adopting “gradual emancipation acts,” laws whose effect would be to eliminate the institution from particular states gradually. (The classic gradual emancipation act, signed into law by New York governor John Jay in 1799, freed New York slaves born after July 4, 1799, when they reached age twenty-eight for males and age twenty-five for females.)

Virginia was not among them. Although Jefferson had cosponsored a gradual emancipation bill in the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1769, its overwhelming rejection by that body led him to put the cause on the back burner. However, he underscored his support for such a law in Notes on the State of Virginia (1781), saying that Virginia slaves eventually would be free, but he claimed to his death in 1826 that public opinion in the Old Dominion had not yet ripened to acceptance of such a reform.

Copyright © 2022 by Kevin R. C. Gutzman

Kevin R. C. Gutzman is a Professor of History at Western Connecticut State University and a faculty member at LibertyClassroom.com. He has his law degree from the University of Texas Law School and his Ph.D. in American history from the University of Virginia. His books include Thomas Jefferson – Revolutionary; James Madison and the Making of America; Virginia’s American Revolution; and, with Thomas Woods, Who Killed the Constitution?