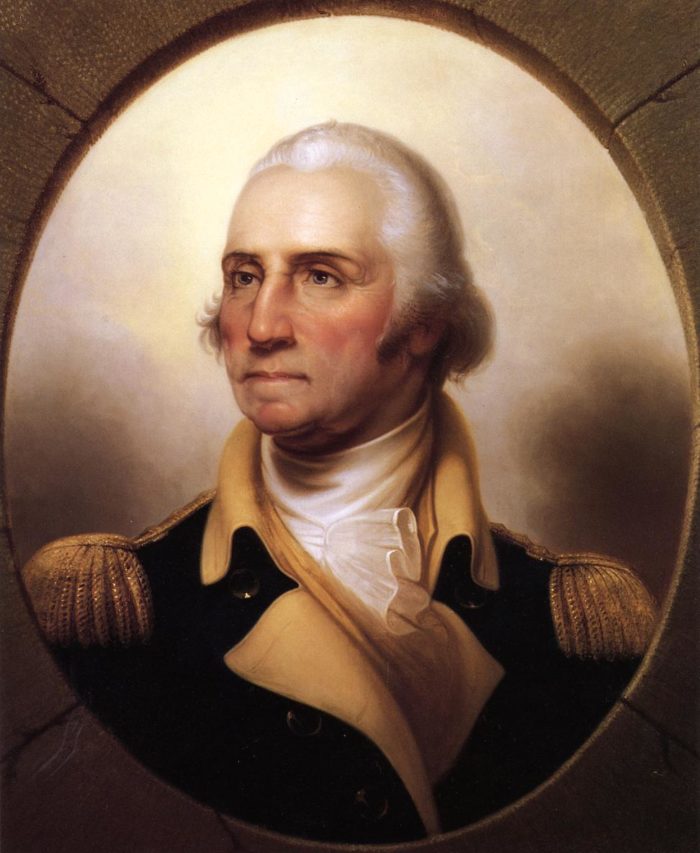

by John Berlau

John Berlau’s biography presents a fresh take on George Washington’s pursuits as a private citizen after his life as America’s most renowned general, covering his many innovations across several industries. The following excerpt discusses Washington’s initial interest in developing a greenhouse at his Mount Vernon residence.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

It was August of 1784, and George Washington had many things on his mind.

He was once again a private citizen, having retired from his position as general six months earlier, after eight years of holding together the ragtag Continental Army and leading it to victory in the Revolutionary War. But he was troubled by the emerging problems of monetary instability in the new nation and its lack of an adequate defense from foreign aggressors. These issues and others would lead him to accept—reluctantly—the nomination to be the first president of the United States some five years later.

But a prime focus of his mind this month had been a more appetizing thought—a plan to grow the then-exotic fruits of oranges, lemons, limes, and others of the citrus variety. Washington had possessed a love of citrus fruits ever since he traveled to Barbados—in what would be his only trip out of the North American continent—at the age of 19 in 1751.

Traveling with his older brother in the hopes that the warm tropical weather would improve Lawrence’s ailing health, the young Washington wrote in his diary of the “many delicious fruits” he had tasted. These included pears, oranges, and pineapples, the latter of which became Washington’s favorite island fruit. “None pleases my taste as do’s [sic] the pine,” Washington wrote. Washington’s business records show that decades later he would frequently order citrus fruits and “a few pine apples” (in his words) from shippers who carried goods to and from the Caribbean.

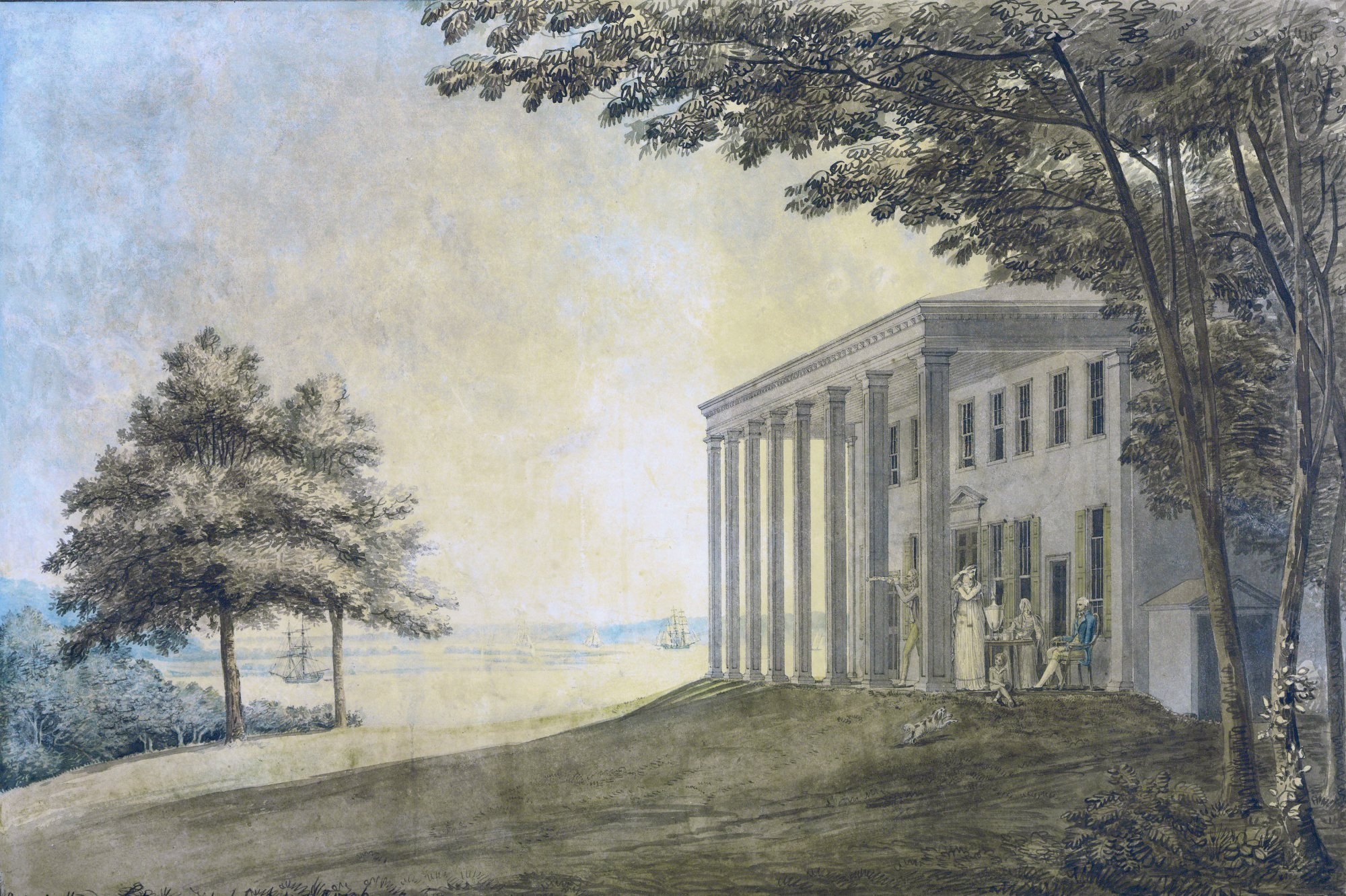

Washington had long wanted to grow these fruits at Mount Vernon, the Northern Virginia farm and estate on which he had lived—off and on—ever since he was a teenager. He knew these crops would not survive the Northern Virginia winters. Over the last few years, however, Washington had read and heard about an agricultural innovation called a “greenhouse” in which these tropical fruits could be grown in environmentally controlled conditions.

The idea of manipulating temperature to grow non-native crops was not new. In ancient Rome, plants were moved in and out of the sunlight to grow certain fruits and vegetables for the emperor Tiberius. In the sixteenth century, separate buildings to house plants and insulate them from rough weather began to be erected by royalty and aristocracy in England and the Netherlands. By the mid-eighteenth century, as technology had made better quality glass more widely available for construction, the royal families and landed gentry erected greenhouses on the grounds of many of Europe’s palaces and estates. Possession of a greenhouse, according to gardening historian Mac Griswold, implied that a landowner had “scaled the heights of power and fashion.”

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

But in the new American republic, in contrast to the nations of old Europe, greenhouses were still few and far between. A handful of greenhouses had been built, including the one constructed in Boston around the 1730s by the Faneuils, a wealthy family of merchants who would later donate to Boston the still-standing Faneuil Hall market and meeting place. However, no greenhouses had been constructed in Northern Virginia, and none of Washington’s friends and neighbors knew how to build one.

Whenever Washington found local knowledge limited he would reach beyond his immediate circle. In this case, he did not have to travel far—only to the neighboring state of Maryland—where there existed a famous greenhouse at Mount Clare, a grand estate in Baltimore that belonged to members of the prominent Carroll family.

Though geographically close, the Carrolls of Maryland were culturally quite a distance away from the Virginia families with whom George and Martha Washington typically rubbed elbows. Irish-Catholics like the Carrolls had fled to America to escape persecution in Great Britain but faced similar prejudice from colonists of English ancestry. In most of the colonies, Catholics couldn’t hold public office, and in Virginia they couldn’t even pray publicly.

But neither Catholics nor other religious minorities faced any prejudice from George Washington. Washington had learned on the battlefield to work with people from all walks of life. Several of Washington’s officers were Irish, including Colonel John Fitzgerald, who served as one of his top aides. Fitzgerald would be a co-founder after the war of Virginia’s first Catholic parish, the St. Mary’s congregation in Alexandria, which continues to this day and was granted “basilica” status by the Vatican in 2018 due to its historic roots.

Copyright © 2020 by John Berlau

JOHN BERLAU is an award-winning journalist, recipient of the National Press Club’s Sandy Hume Memorial Award for Excellence in Political Journalism, and Senior Fellow for Finance and Access to Capital at the Competitive Enterprise Institute. He is a columnist for Forbes and Newsmax, and has contributed to Financial Times, Washington Post, Politico, Wall Street Journal,and Washington Times. He is a frequent guest on CNBC, CNN, Fox News, and Fox Business. He lives near Mount Vernon in Alexandria, VA.