by Erin Lindsey

“I do not believe there ever was any life more attractive to a vigorous young fellow than life on a cattle ranch in those days.”

–Theodore Roosevelt

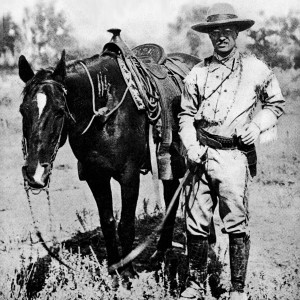

The 26th President of the United States appears in our history books in a great many guises. Trust-buster and reformer. Naturalist and historian. Hunter and conservationist. Rough Rider and unapologetic imperialist. But perhaps no aspect of Theodore Roosevelt’s larger-than-life legacy captures the imagination quite like his time as a cowboy on the American frontier. To this day, when many of us picture Theodore Roosevelt, we think of him sitting astride a horse, rifle in hand. This image of the rugged outdoorsman has become so etched in our collective consciousness that it’s hard to imagine just how incongruous it would have appeared at the time, especially to TR’s peers among the New York elite. The Roosevelts were, after all, a Knickerbocker dynasty, a symbol of Old New York at a time when even the Vanderbilts were considered nouveaux-riches. So how did a New York aristocrat come to be so intimately associated with the rough-and-tumble men of the frontier?

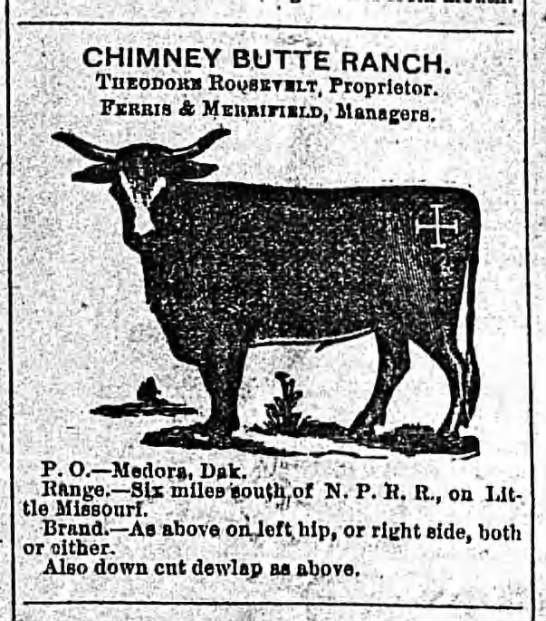

Roosevelt’s love affair with the west began in 1883, when he headed out to the Dakota Territory on a buffalo hunt. Bison were few and far between by that time; in their place, longhorn cattle were being driven up from Texas to gorge themselves on the plentiful grasses. Ranching was a booming business, and many a deep-pocketed easterner was keen to invest. For Roosevelt, who had long romanticized “manly” pursuits in the great outdoors, the prospect of ranching held great appeal. He managed to convince local cowhands Sylvaine Ferris and Bill Merrifield to go into business with him, and before his hunting trip was over, he’d signed a check for $14,000 (more than his annual salary as an assemblyman) and instructed his new managers to build him a cabin to act as home base for his fledgling cattle concern. The Maltese Cross cabin was duly erected eight miles south of Medora, in present-day North Dakota.

A few months later, on February 14, 1884, tragedy struck: Roosevelt’s mother passed away, followed only hours later by his wife, Alice, who had given birth to their first child days before. Roosevelt was devastated, and when the legislative session ended in June, he promptly headed out west to forget his grief and lose himself in the vast wilderness of the Dakota Territory. “Black care,” he wrote, “rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough.”

Shortly after arriving, he found a new place to hang his hat: a stretch of bottomland along the Little Missouri River north of Medora, which he claimed for his second ranch.

“I built on the Elkhorn Ranch a long, low ranch house of hewn logs, with a veranda, and with, in addition to the other rooms, a bedroom for myself, and a sitting-room with a big fireplace. I got out a rocking-chair—I am very fond of rocking-chairs—and enough books to fill two or three shelves, and a rubber bathtub so that I could get a bath. And then I do not see how any one could have lived more comfortably.”

Roosevelt threw himself into the ranching life with typical TR zeal. Unlike most of his fellow eastern capitalists, who were content to leave the rough business of driving, roping, and branding to their ranch hands, Roosevelt insisted on being in the thick of it, breaking his own ponies and joining in the spring roundup. What he lacked in skill he made up for in bullish determination, and those who initially dismissed him as just another eastern dude quickly learned that he had “sand in his craw aplenty”.

At the height of his badlands adventures, Roosevelt had about 3,200 cattle, plus another thousand calves. But his investment – and those of many of his fellow ranchers – would ultimately prove disastrous. An incredibly harsh winter in 1886-1887 wiped out tens of thousands of cattle in the badlands. Roosevelt lost up to 65% of his “backwoods babies”, a crippling financial loss. This devastating turn of events serves as the backdrop for The Silver Shooter, a Wild West mystery featuring Theodore Roosevelt as a character. It marked the beginning of the end of Roosevelt’s stint in the badlands, and it’s tempting to speculate how history might have unfolded differently were it not for that terrible winter.

Brief though it may have been, TR’s time as a cowboy had a lasting impact. His love of the wild open country he’d once ridden over fueled his conservationist spirit, a legacy that endures to this day. During his presidency, Roosevelt protected 230 million acres of public land and unveiled five new national parks. Especially in these times of restricted movement, it’s a blessing to have our national parks to enjoy, and for that, we can thank the Cowboy President.

Erin Lindsey has lived and worked in dozens of countries around the world, but has only ever called two places home: her native city of Calgary and her adopted hometown of New York. In addition to the Rose Gallagher mysteries, she is the author of the Bloodbound series of fantasy novels from Ace. She divides her time between Calgary and Brooklyn with her husband and a pair of half-domesticated cats. Visit her online on her website, twitter and facebook.