by Michael Wolraich

Theodore Roosevelt and Terrorism

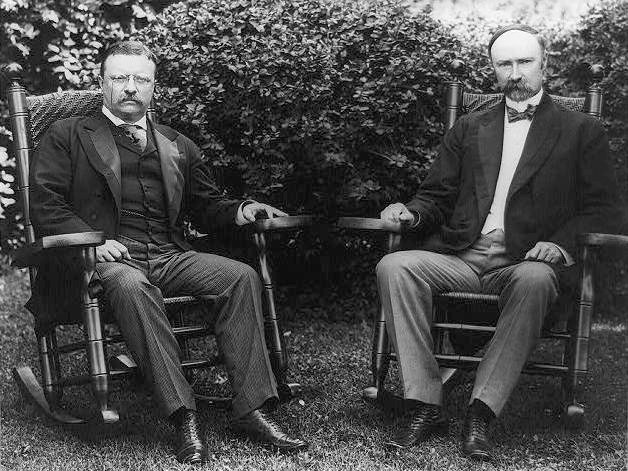

Some years ago, an unstable young man committed one of the most notorious terrorist acts in U.S. history. He was American-born, but his parents were immigrants, and his allegiance to a radical ideology with foreign origins terrified the public. “They and those like them should be kept out of this country,” railed Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States, “and if found here they should be promptly deported to the country whence they came.”

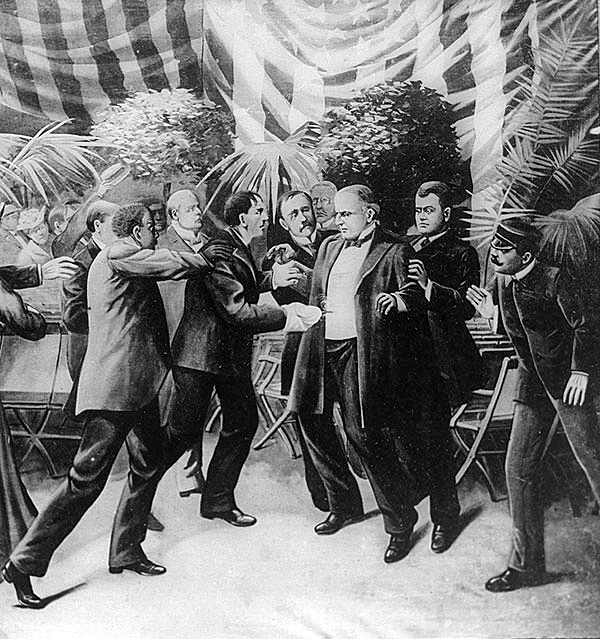

The young man was Leon Czolgosz, a Polish-American anarchist. On August 31, 1901, he fatally shot President William McKinley in the abdomen with .32 caliber revolver. The nation reacted with shock and outrage. McKinley’s successor, President Theodore Roosevelt, denounced anarchy as “a crime against the whole human race” and demanded legislation to restrict immigration and deport suspected anarchists. Congress answered the call with the Anarchist Exclusion Act, which barred anyone “who disbelieves in or who is opposed to all organized government” from becoming citizens.

Today, history is repeating itself. We have our own Leon Czolgosz—an unstable young man named Omar Mateen who pledged allegiance to ISIS as he murdered 49 innocent people. Like Czolgosz, Mateen is an American-born son of immigrants, and his crime has provoked calls to bar Muslim immigrants. Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump is naturally leading the charge. “If we don’t get tough, and we don’t get smart and fast, we’re not going to have our country anymore,” he warned. “There will be nothing, absolutely nothing left.”

But before we get too excited about passing a Muslim Exclusion Act, we would do well to take lessons from America’s original war on terror. In the early 1900s, many Americans saw anarchism as an existential threat, much the way Mr. Trump and others view radical Islam today. They feared that hordes of European anarchists were secretly plotting to destabilize the country and indoctrinate the youth with dangerous ideas. “We open our arms to the human sewage of Europe,” protested the Washington Post. “The nation which offered itself as an asylum for the oppressed has been turned into a lurking place for murderers,” warned the San Francisco Chronicle.

It was a farce, of course. Anarchist ideas influenced some labor activists and inspired a few terrorist attacks but never posed a serious threat to the country, and the movement petered out within a few decades. The only threat to our liberty was the public’s overwrought response to anarchism-inspired crimes. The Anarchist Exclusion Act was first in a series of repressive laws targeting immigrants and dissidents, including the the Espionage Act of 1917, the Sedition Act of 1918, the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, and the Immigration Acts of 1917, 1918, and 1924. The anarchist hysteria peaked with the notorious trial of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in 1921, during which two Italian immigrants with anarchist ties were sentenced to death with insufficient evidence.

Today, we look back at this era with shame. The alleged anarchist plots that seemed so frightening at the time faded into obscurity; only the country’s intolerance and narrow-mindedness stand out from the pages of history. Our current obsession with Islamic extremism will be much the same. A century from now, historians will dismiss the so-called war on terror as an overreaction inflamed by xenophobia and bigotry, and Donald Trump’s name will be lumped with other notorious demagogues from American history like Father Coughlin and Joseph McCarthy.

In the meantime, we can take some solace in the words of Theodore Roosevelt, who tempered his attitude toward immigration during his second term. “We must treat with justice and good will all immigrants who come here under the law,” he told Congress in 1906, “Whether they are Catholic or Protestant, Jew or Gentile; whether they come from England or Germany, Russia, Japan, or Italy, matters nothing…It is the sure mark of a low civilization, a low morality, to abuse or discriminate against or in any way humiliate such stranger who has come here lawfully and who is conducting himself properly. To remember this is incumbent on every American citizen, and it is of course peculiarly incumbent on every Government official, whether of the nation or of the several States.”

Michael Wolraich is the author of Unreasonable Men: Theodore Roosevelt and the Republican Rebels Who Created Progressive Politics (Washington Post “50 notable works of nonfiction”). He has also contributed to the Daily Beast, RollingStone, the Atlantic, New York Magazine, CNN.com, Talking Points Memo, and Reuters.