by Kostya Kennedy

True: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson by Kostya Kennedy is a probing, richly-detailed, unique biography of Jackie Robinson, one of baseball’s—and America’s—most significant figures. Read an excerpt below.

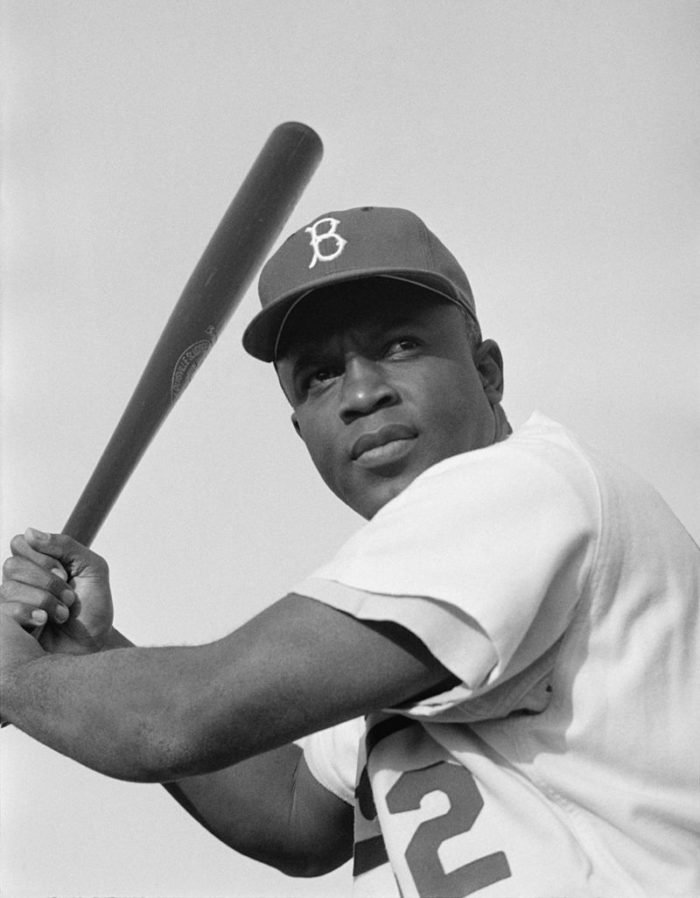

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People began awarding the Spingarn Medal in 1915, six years into the organization’s existence. Per instruction of J. E. Spingarn, the award’s creator and then chairman of the NAACP’s board, the medal was to honor “the highest or noblest achievement by a living American Negro during the preceding year or years.” (Today the language reads: “for the highest achievement of an American of African descent.”) The medal, made of solid gold, is awarded annually, with the recipient determined by committee. The first Spingarn Medal went to Ernest Everett Just, a cellular biologist and a professor at Howard University. W. E. B. Du Bois received the award in 1920, George Washington Carver in ’23. Mary Bethune Cookman in ’35, Thurgood Marshall in ’46. Over its first four decades, the Spingarn Medal went to educators, writers, civil rights advocates, scientists, musicians, political leaders, lawyers, historians, actors, activists, and businesspeople, among others. Never did it go to an athlete: not Jesse Owens or Joe Louis or Sugar Ray Robinson—or others who had broken boundaries or achieved the pinnacle of their sport.

When, in the late spring of 1956, the NAACP committee prepared to select that year’s Spingarn Medal recipient, powerful candidates emerged. Conspicuously, there was Autherine Lucy, a twenty-six-year-old English teacher who, after a three-year court battle, had won the right to attend the University of Alabama as the school’s first Black student. Her presence, in February, led to campus rioting—a car she rode in was pelted with rocks, her classroom came under siege by a mob—and soon thereafter, the university expelled her, defying a court order. “They stoned me, they cursed me, they burnt me in effigy, but they did not discourage me,” Lucy wrote describing the riots. In articles and in public speeches, Lucy vowed to press on until she “and others of [her] race” had their rightful access to education.

“For the life of me, I can’t understand how the NAACP could pass over a great and courageous person like Autherine Lucy in making the Spingarn Award,” wrote Ralph Ewing, a reader from Detroit, to Baltimore’s Afro-American after the medal winner was announced.

Another candidate for the Spingarn Medal that year was Martin Luther King Jr. Since December of 1955, he had been at the forefront of what was developing into a watershed of the civil rights movement, the Montgomery bus boycott. Already, the boycott’s implications beyond the bounds of the city, and the state of Alabama, were becoming apparent. “We are in the midst of a great struggle, the consequences of which will be world-shaking,” Dr. King said from his pulpit at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery. He and other leaders of the boycott had been arrested, threatened, and buffeted by violence—someone had exploded a bomb on the porch of the Kings’ home—and had not bent. When Dr. King came to Brooklyn in March, to speak at the Concord Baptist Church, ten thousand people turned out and gave him a reception, as one newspaper described it, “usually reserved for its favorite heroes, the Dodgers.” By late April, more than a dozen bus companies in the South had abandoned their policies of segregation.

At twenty-seven, Dr. King was determining the tone of the larger movement and defining the principles that would sustain his leadership in the decade to come. “If we are arrested every day, if we are exploited every day, if we are trampled over every day, let nobody pull you so low as to hate them,” he preached to a massive crowd in Montgomery. “We must use the weapon of love. We must have compassion and understanding for those who hate us. So many people have been taught to hate us, taught from the cradle.”

In the words that he preached and in the words that he told himself during that time, King echoed the spirit that had guided Robinson through his groundbreaking years in baseball, the same bottom line: “You must be willing to suffer the anger of the opponent and yet not return anger,” King said in self-admonishment after succumbing to rage and indignance during the bus boycott. “You must not become bitter. No matter how emotional your opponents are, you must be calm.” He had completed a doctorate in systematic theology, and had found along the way a lodestar in Gandhi, who, as King described it, had “lifted the love ethic of Jesus above mere interactions between individuals to a powerful and effective social force.”

Dr. King also did not receive the Spingarn Medal in 1956 (he received it the following year), although both he and Autherine Lucy attended, and addressed, the NAACP’s annual convention, where the medal was traditionally presented. In San Francisco, over several days of speeches and events in late June (Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP’s lead lawyer, delivered the keynote; Marshall and King debated policies around school segregation), the Spingarn Medal, while cited, was not, in fact bestowed. Its recipient hadn’t made it to the convention, on account of his having work obligations in Brooklyn.

“It is beyond question the thrill of my lifetime,” Robinson said when told he had been named the Spingarn winner. He’d taken the phone call at his home in Stamford. Plaques commemorating his many years of athletic achievement hung densely on a paneled wall, and the garden outside the windows was entering its summer bloom. “You can’t emphasize too much how very pleased I am.”

According to the NAACP’s executive secretary, Roy Wilkins, Robinson was chosen for “his superb sportsmanship, his pioneer role in breaking the color bar in organized baseball and his civic consciousness.” News of Robinson’s honor received considerable attention, within and without the Black press. A baseball player! There had come to be a greater understanding of how far outside the boundaries of sports Robinson resounded. “His entrance into organized baseball has done as much as anything else to bring about understanding in this country,” suggested Muriel Richardson of Charlottesville, to the Afro-American. A columnist for the Alabama Tribune in Montgomery wrote, “Those who have known second-class citizenship, the humiliating scars of denial, segregation, discrimination and those fringe monsters of Jim Crow will understand the torment that Jackie suffered in breaking the colorline. Few Americans have been more deserving of the Spingarn than Jackie.”

That December, at a Saturday luncheon in the Palm Room at the Hotel Roosevelt on Madison Avenue in the center of Manhattan, Robinson accepted the medal. The newspaper columnist and television host Ed Sullivan presented, and when he did, and Robinson went to the lectern, the room stood in prolonged ovation. “To be honored in this way means more than anything that has happened to me before,” Robinson said. “The NAACP represents everything that a man should stand for—for human dignity, for brotherhood, for fair play.”

Thurgood Marshall and W. E. B. Du Bois and Floyd Patterson sat among the audience, and all the tables were full, and Robinson’s speech kept getting interrupted by applause. “And now, with your indulgence, I would like to ask my wife to come and share this honor with me,” said Robinson, and as Rachel rose from her seat on the dais, so, too, did the guests rise from their seats at the tables, and the room rocked again with fervent clapping and the chandeliers shook as Rachel came forward and stood at Jackie’s left side. “It is hers fully as much as it is mine,” he said of the Spingarn honor. “My career and whatever success I have attained were made possible by my beloved wife.… She is the principal reason I am standing here today.” Jackie Jr., ten years old, sat on the dais alongside members of the NAACP board of directors.

On that afternoon—buoyed by the weight and the implication of the Spingarn Medal—Robinson was in part looking toward his time after baseball, for ways he might extend and enhance the mission of his life. He knew that his public strength would always emanate from his immutable accomplishment as a ballplayer. “He was a freedom rider before freedom rides,” Martin Luther King Jr. would later say. For all Robinson’s activism and stoicism in the years to come, for all the stands he would take and the language he would use, Robinson’s most searing eloquence would remain rooted in the way he shook the foundation as a young man. From the first moment he stepped onto a baseball field as a Montreal Royal to the last time he left the diamond with the Dodgers logo stitched across his breast, Robinson gave to the world a profound and enduring expression, articulated in the way that he played the game.

Copyright © 2022 by Kostya Kennedy. All rights reserved.

Kostya Kennedy is an editorial director at Dotdash Meredith and a former senior writer at Sports Illustrated. He is the New York Times bestselling author of 56: Joe DiMaggio and the Last Magic Number in Sports (runner-up for the 2012 PEN/ESPN Award for Literary Sports Writing) and Pete Rose: An American Dilemma. Both won the CASEY Award for Best Baseball Book of the Year. He has taught at Columbia and NYU, and lives with his wife and daughters in Westchester County, New York.