by Clayborne Carson

I saw Martin Luther King Jr. proclaim his Dream at the 1963 March on Washington. King captured the nation’s attention, and his legacy ultimately became the focus of my career. In the days before the march, however, my understanding of his significance changed when I met Stokely Carmichael, a young black activist affiliated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Stokely made me aware that King was only one aspect of a sustained Southern freedom struggle to overcome the Jim Crow system of racial segregation and discrimination. Although I continued to admire King, I learned that the brash protesters and “field secretaries” of SNCC were key components of a community of dedicated activists I would come to know as the Movement. They exemplified the rebelliousness and impatience I felt as a teenager.

I had grown up as one of a handful of African American residents in Los Alamos, a small New Mexico town far from the frontlines of the Southern protest movement. Nonetheless, I paid close attention to news about civil rights activities—especially when black students near my own age were involved. When I was in eighth grade, the Little Rock Nine students were braving white mobs to desegregate Central High School. While I was in high school, I read about the student-led lunch-counter sit-ins and the freedom rides. During the months before the 1963 march, President John F. Kennedy stirred me with his televised speech urging Americans to see civil rights as a “moral issue,” although I wondered why it took him so long to recognize this. While courageous young black activists were battling entrenched racial oppression and capturing the nation’s attention, I resigned myself to return to Albuquerque for my second year at the University of New Mexico (UNM).

Several days before the March on Washington, I traveled to Bloomington, Indiana, as part of UNM’s delegation to the National Student Association’s (NSA) annual convention. Stokely, a Howard University senior, was representing SNCC. I was vaguely aware of SNCC’s involvement in the sit-ins, freedom rides, and Deep South voting rights campaigns, but Stokely seemed to be a knowledgeable Movement veteran. His lanky build, intense demeanor, and copious confidence made him a magnet of attention at convention sessions and impressed me to the point of envy.

As the only black student on the UNM delegation to the NSA conference, I felt a special responsibility to inform myself about the convention’s most contentious issue: whether the organization should support the upcoming March on Washington. I listened as Stokely insisted that the NSA not only back the march but also give financial support to SNCC.

His arguments were peppered with sardonic criticisms of cautious liberalism. Some delegates warned that passing the resolution favoring the march would prompt the withdrawal of Southern white colleges from the NSA, perhaps fatally damaging the organization.

When I took part in an informal caucus of delegates supporting Stokely’s position, I observed him up close as he guided the discussions. At first, his unfamiliar accent made me wonder whether he was a foreign student. I learned that his parents were immigrants from Trinidad but that he had spent his teenage years in New York. I wasn’t surprised when he mentioned that he was a philosophy major. As he described SNCC’s projects, I found it remarkable that a small group of young people had taken on the ambitious mission of overcoming Southern racism. I also realized how much I was missing while attending a predominantly white university so distant from the Southern, student-led protests of the early 1960s.

During the meetings I didn’t feel confident enough to contribute to the discussions and hoped that my presence was enough to indicate support. When I had my only chance to speak privately with Stokely, I confided that I hoped to attend the March on Washington, perhaps thinking this would assure him that I was not a complete bystander in the Southern struggle. “Who cares about that middle-class picnic?” he retorted. “If you really want to help the movement, get involved in one of SNCC’s projects and get a taste of the real movement.” I said I would think about it but knew that I would almost certainly return to school in pursuit of becoming the first college graduate in my family. Although I had no quick answer to his challenge, his words stuck in my mind.

My understanding of SNCC was also affected by a long conversation at the conference with Lucy Komisar, the young white woman who edited the Mississippi Free Press. Lucy patiently explained the crucial, yet largely ignored, battles over black voting rights taking place in Mississippi. She told me about Bob Moses, a former high school math teacher from New York who had initiated SNCC’s voter registration efforts in the state, and about the 1961 killing of civil rights advocate Herbert Lee by a white Mississippi legislator who was quickly exonerated by an all-white coroner’s jury. Lucy even took the time to teach me some freedom songs.

Stokely and Lucy, in their very different ways, made me aware that people close to my age were moving beyond just voicing their support for civil rights by dedicating their lives to the struggle. They convinced me that SNCC was at the forefront of a nonviolent crusade against white supremacy in its Deep South strongholds. Although I was not ready to drop out of college to fight on the Movement’s frontlines in the Mississippi Delta, Selma, Albany, Danville, Cambridge, and other places, my impetuous curiosity had a new focus. By the time NSA delegates voted lamely to back the goals of the March on Washington but not the march itself, my perspective had shifted toward SNCC’s. I began to realize that King, the nation’s best-known civil rights leader, was part of a freedom struggle seeking far-reaching changes and led by grassroots activists whose names were rarely in the newspapers. It would be three years before I saw Stokely again, but that first encounter strengthened my determination to find some way to connect with the Movement.

When I confirmed that a ride to the march was available on a bus chartered by an Indianapolis National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) group, I eagerly agreed to go and told my UNM colleagues that I would not be returning to New Mexico with them. I didn’t bother to tell my parents about my plans. Dad might not have objected, but Mom almost certainly would have insisted that I not participate in any demonstration, and she was the dominant, sometimes domineering parent.

I left my suitcase in a locker at the Indianapolis bus station and boarded a bus full of strangers that left early on the evening of August 27. I had less than fifty dollars in my wallet and a return bus ticket from Indianapolis to Albuquerque. It was my first trip to Washington, my first venture so far from home, and my first demonstration of any kind, but I don’t remember feeling anxious or uncertain. I was confident that my impromptu adventure would turn out well.

The bus arrived in Washington the next morning, and I was exhausted by my choice to give up hours of sleep to talk to Sylvia, a winsome Jewish teenager. We promised to stay in touch but didn’t. As I got off the bus, an elderly black man, who must have quietly observed me during the ride, pushed a twenty-dollar bill into my hand, guessing correctly that I was worried about having enough money to return home.

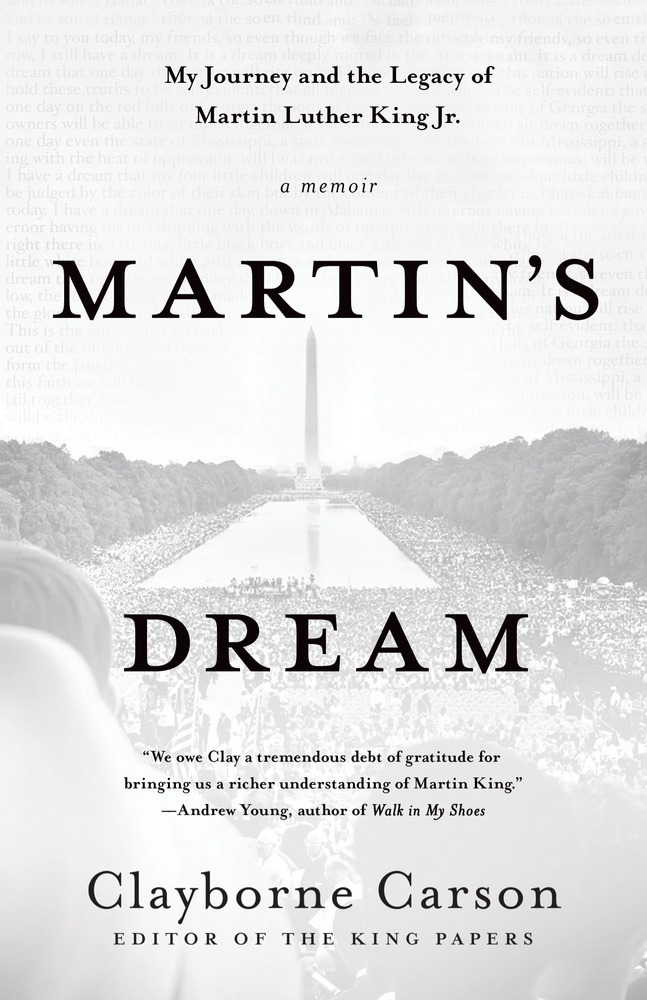

My memories of the remainder of that day are a mixture of vague and vivid impressions. I was amazed by the multitude of marchers—many more black people than I’d ever seen growing up in New Mexico. Accustomed to dry mountain crispness, I found it hard to adjust to the hot, humid air. I was impressed that most of the adults were well dressed in the sweltering heat, but the sweat on my white cotton shirt compelled me to take off my sport coat.

I decided against carrying one of the official printed placards offered to me so that I could dart around the slowly moving marchers. Self-consciously aware that I don’t sing well, I only intermittently joined in the endless choruses of “We Shall Overcome.” I noticed a black contingent from Mississippi who energized the crowd by snaking through the marchers shouting some of the spirited freedom songs that Lucy had taught me. Although I imagined that most black Mississippians lived in conditions only slightly removed from slavery, these demonstrators exhibited a sense of freedom that I found enticing. My shyness inhibited me from talking to other young marchers, who seemed to be with families or groups.

Approaching the Lincoln Memorial, I edged through the crowd toward the speakers’ platform to get a closer view of the famous people who were being introduced. I recognized some of the scheduled singers from appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show, which my family regularly watched on Sunday nights. I never imagined seeing Marion Anderson, Mahalia Jackson, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, and Bob Dylan in person. Actor and playwright Ossie Davis announced that W. E. B. Du Bois, the NAACP founder and famous author of Souls of Black Folk, had just died in Ghana, having exiled himself there after becoming a victim of anticommunist hysteria. In the early afternoon, after the Tribute to Women Freedom Fighters (including student activist Diane Nash Bevel and the recently widowed “Mrs. Medgar Evers”), the sticky heat led me to join the people who removed their shoes to cool their feet in the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool.

Because of my new awareness of SNCC’s significance, I felt a special sense of anticipation when march director A. Philip Randolph introduced John Lewis, SNCC’s newly elected chairman and, at twenty-three years old, the youngest speaker on the program. I knew by then that he had been a Nashville sit-in leader and one of the freedom riders who were imprisoned in Mississippi during the spring of 1961.

His rural Southern cadence contrasted sharply with Stokely’s urbanity, but Lewis also exemplified SNCC’s militancy and took the risk of alienating some of his listeners. Rather than merely calling for passage of the Kennedy administration’s civil rights proposal, he drew attention to its lack of provisions to protect peaceful protests from police brutality or to enable black residents of the Deep South to register to vote. “One man, one vote is the African cry,” he announced. “It is ours, too.” Departing from the bland tone of preceding speakers, he insisted, “The revolution is at hand, and we must free ourselves of the chains of political and economic slavery.”

Lewis expressed a sense of urgency that I would soon share: “We want our freedom, and we want it now.” Rather than depending on the two major political parties (“both the Democrats and the Republicans have betrayed the basic principles of the Declaration of Independence”), he placed his faith in grassroots militancy. “We all recognize the fact that if any radical social, political and economic changes are to take place in our society, the people, the masses, must bring them about,” he explained. I was pleased that Lewis’s call for a nonviolent revolution elicited a few bursts of enthusiastic applause.

By the late afternoon hour when King was introduced to speak, I was preoccupied with thoughts of finding the bus that had brought me, but I didn’t want to miss his remarks. I edged my way toward the rear of the crowd, so that I could quickly depart when he finished speaking. His initial words confirmed that my decision to attend the march was wise.

“I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation,” he began. I had no basis for determining the march’s historical significance, but I wanted to believe King. Many of the previous speakers had lauded Kennedy’s proposed civil rights legislation, but King’s address instead suggested a broader transformation of the nation’s race relations. At the time, I didn’t fully understand his challenge to “the architects of our republic” or his cascade of biblical and historical references, but his metaphorical, tradition-laden diction strengthened my sense of the march’s importance. John Lewis’s call for radical change had disrupted my complacency, but King transformed “Freedom Now!” into passionate poetry:

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood.

How could I have known then that I was listening to a great speech rather than simply the last in a long program on a sweltering day? I cannot remember exactly when I learned that King’s address even had a name, but I later discovered that the “I Have a Dream” refrain was extemporaneous—a last-minute extension of his prepared remarks. I couldn’t imagine having the confidence to speak to so large an audience on such an important occasion and then make up a new ending on the spot.

King’s rousing conclusion would soon become embedded in my memory, but discovering its deeper meanings would take many decades. It is likely that my immaturity, my lack of historical and religious knowledge, and the distraction of finding a ride prevented me from fully appreciating King’s “dream deeply rooted in the American dream.”

Failing to find my original bus, I impulsively accepted an invitation to ride with a group from Brooklyn. Still half asleep when I arrived at Penn Station, I took the subway to Harlem, guessing that I could find an inexpensive place to stay for the night. After asking for directions to a cheap hotel, I instead paid a few dollars to sleep on a stranger’s couch. I spent the next morning gawking at the skyscraper canyons of central Manhattan before exchanging my bus ticket from Indianapolis to Albuquerque for a ticket from New York to Indianapolis.

Only then did I call Mom collect to explain, as imprecisely as possible, my sudden detour. I told her about finding a ride to the march and then meeting a group from New York, but said little about how I planned to return home. I didn’t really have a plan—only that I would figure things out after getting some much-needed rest on the bus. The tone of her voice told me that she was not pleased, but fortunately she didn’t want to run up a large phone bill talking to me.

I would never tell my parents that I hitchhiked the remaining 1,300 miles from Indianapolis to Albuquerque. A succession of short rides brought me to Illinois, where a black couple offered a ride to St. Louis. When they awakened me well after midnight, I was too groggy to understand where I was and had to walk for several hours to find the interstate highway.

The next night, I survived a harrowing experience in Oklahoma when a middle-aged white man stopped for me and then immediately warned, “I’ll shove you out of this car, if you cause any trouble.” I wondered why he gave me a ride, but surmised that he wanted to talk to someone. His slurred voice and erratic, high-speed driving betrayed that he was drunk. “Don’t worry,” he assured me. “I helped design this highway. I know it like the back of my hand.” Predictably, he hit a median curb, and the car careened across the roadway before he regained control. Even though it was past midnight, I insisted that I would rather walk. I found a place to rest until the next morning.

After a few more rides, I reached the Albuquerque bus station. When my parents met me there, I had already claimed my luggage and changed into fresh clothes. I did my best to disguise the fact that I was dead tired after more than two days on the road.

The march became the link between my childhood and all the remarkable and unexpected things that later happened to me as an adult. Yet, after spending decades trying to make sense of my experiences there, I still had some unanswered questions. If I had been unable to find a ride to the march, would my life have been very different? Why was I so unconcerned about how to return home? Why did I accept a ride from the march to New York, even though I had little money, and my bus ticket was from Indianapolis back to New Mexico? Why didn’t I call my parents to ask them for bus fare to get home? And why was I so attracted to SNCC’s worldview, so ready to change the course of my life?

My march memories began to make more sense as I came to see them through a historical lens. At the march, I didn’t yet have a historian’s habits—I didn’t think to keep mementos or even take snapshots to preserve the details of the experience. My fleeting memories are frail pillars to carry the weight I have since placed on them. Most of what I now know about the march comes from research, not memory, but I’ve learned that history and autobiographies are edited versions of the past that always leave unanswered questions. When people ask me how it felt to be at the march, I find it hard to give an answer. It would be years before I grasped the full significance of that special day.

Clayborne Carson is professor of History at Stanford University and director of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute, and also helped to design the King National Memorial. Selected in 1985 by the late Mrs. Coretta Scott King to edit and publish Dr. King’s papers, Carson has devoted most of his professional life to the study of MLK. He has spoken about Dr. King and his legacy throughout the world, and has appeared on many national radio and television shows, including Good Morning America, NBC Nightly News, CBS Evening News, The NewsHour, Fresh Air, Morning Edition, Tavis Smiley, Charlie Rose, Democracy Now, and Marketplace. Carson has also served as a historical advisory for numerous documentaries, including “Freedom on My Mind,” which was nominated for an Oscar in 1995.