by Professor John Coleman Darnell and Dr. Colleen Darnell

Egyptologists and authors of Egypt’s Golden Couple, Professor John Coleman Darnell (Yale University) and Dr. Colleen Darnell reveal some of the findings they have made pertaining to King Tut to celebrate the 100-year anniversary of the discovery of his tomb on November 4th.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

A century ago, the work of Egyptian excavators, decades of fieldwork by archaeologist Howard Carter, and the patronage of the Fifth Earl of Carnarvon, led to the discovery of the nearly intact tomb of Tutankhamun. Untouched for over three thousand years—since necropolis guards and ancient administrators resealed the tomb after thieves rifled through the outer chamber—Carter described his first glimpse of the tomb as “gold—everywhere the glint of gold.”[1]

Yet for all of the tomb’s remarkable artifacts, including an otherwise unattested religious composition written in cryptographic hieroglyphs, Tutankhamun’s tomb reveals little about the history of his reign or that of his predecessors, Akhenaton and Nefertiti, the subject of our book, Egypt’s Golden Couple. Much more information about the world of Tutankhamun comes not from glittering gold objects, but in the form of hieroglyphic texts carved onto stone stelae, and from cursive inscriptions and rock art scratched into the very sides of desert cliffs. Tutankhamun has become known as the “boy king,” but the nine years of his reign witnessed more than merely the brief rule of a young pharaoh. As Egyptologists and archaeologists, we have been fortunate both to discover and to translate texts that have changed our understanding of the reign of the king who now enjoys more fame than any other ruler of ancient Egypt.

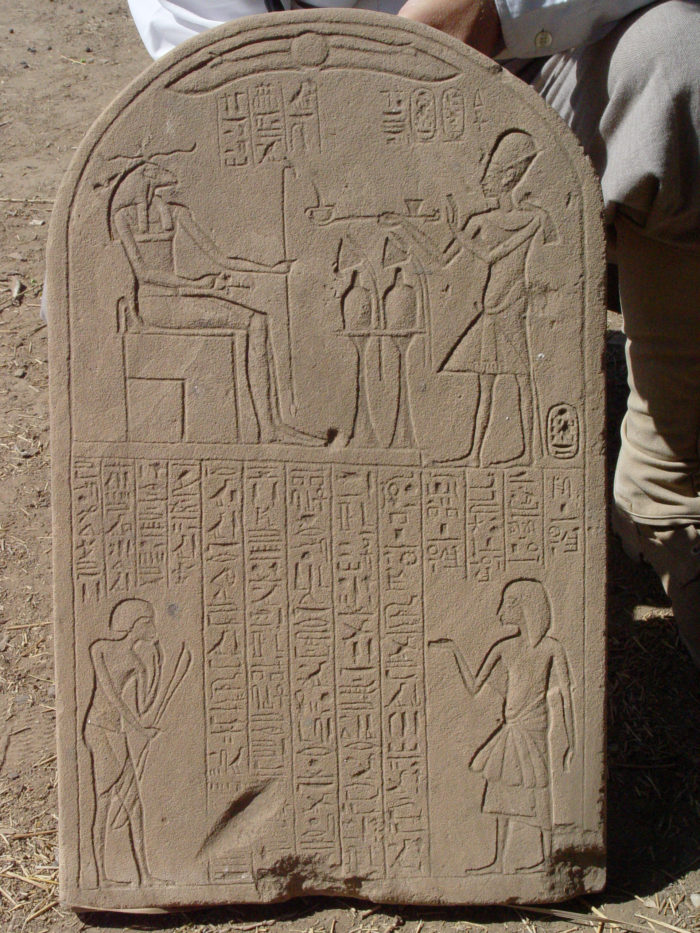

As director of the Yale Toshka Desert Survey Project, John mapped ancient routes through the desert southwest of Aswan in southern Egypt. In antiquity, these tracks were used both for trade and for police patrols to monitor the area and guarantee the safety of travelers. In 1997, Egyptian soldiers stationed in the same area discovered a stela from the reign of Tutankhamun, and John soon thereafter prepared a translation of the hieroglyphic text.

Image credit: Yale University Toshka Desert Survey Project.

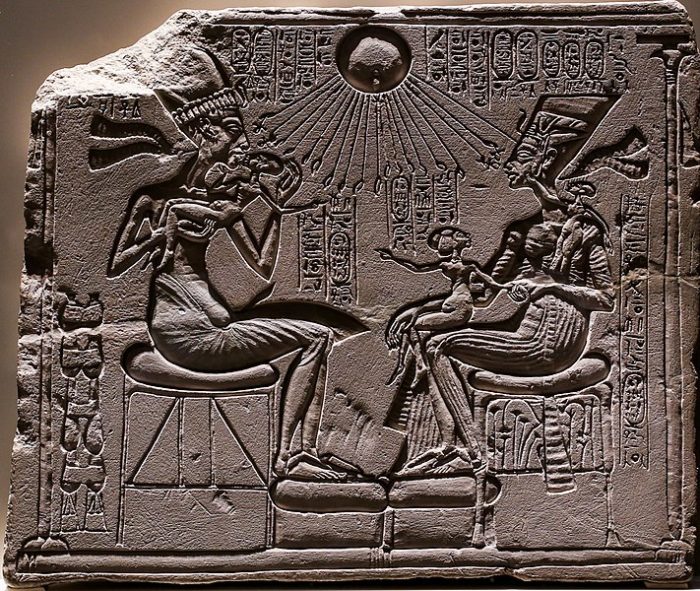

John was surprised to discover that the monument preserved not a royal decree or a list of prayers to local deities, but rather a dialogue between a Nubian patrolman and an Egyptian administrator who oversaw part of Egypt’s province in Nubia. Apparently, the Nubian patrolman was late to pick up a seal, probably a key element in border surveillance. While the Egyptian administrator chides the patrolman for being late, and the patrolman in turn defends himself with a description of his long and grueling daily journey, the entire stela serves as a snapshot of Egypt’s southern domains. The top of the stela shows the king offering to Khnum, the ram-headed god responsible for the Nile floods—as pharaoh, Tutankhamun is tasked with maintaining cosmic balance, which the ancient Egyptians termed maat.

The two men conversing below are but a small portion of that grand plan as it applied to Nubia. Even a low-ranking patrolman had a right to explain his delay, and even a high-ranking Egyptian administrator showed himself an effective and compassionate manager. This conversation from 3300 years ago occurred while Tutankhamun was king—not a golden treasure, but a historical gem nonetheless.

In our work together in the Eastern Desert of Egypt, we have uncovered new information about the source of Tutankhamun’s riches, the metal that would become his solid gold coffin and iconic funerary mask. A wadi (dry desert canyon) on the east bank of the Nile across from the city of Edfu, famous for its well-preserved Ptolemaic temple, provided access to the northernmost roads to the rich gold mines of southern Egypt and northern Nubia. For over a century, ancient rock inscriptions had been known in that wadi, and yet careful survey in conjunction with our colleagues at the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities has led to the discovery of dozens more, carved between 4000 BCE and the late Roman era.

In the 1840s, a Prussian expedition discovered a block in this same wadi that bore the cartouches of Tutankhamun. The sandstone block, likely once part of a shrine constructed in the name of the young pharaoh, was reused in a Roman fortress, but the stone’s location was lost by the early 1900s. Not far from that Roman fort and the well it guarded, in 2017 we discovered another block from Tutankhamun’s lost temple. The fragmentary inscription mentions Nekhbet, the vulture goddess of Upper Egypt, who protected travelers along this road. Nearby, we also found a remarkable hieroglyphic inscription carved by a man named Hori, who lived about seventy years before Tutankhamun. Hori prays to Horus (chief god of Edfu) and Nekhbet so that the gods might grant him “water in the well and gold in the mountain.”

When we stand in awe before the gold mask of Tutankhamun, we should also marvel at the bureaucratic and logistical accomplishments of the ancient Egyptians. Tutankhamun himself may have further developed access to crucial water resources along the routes to the gold mines as well as enhancing border patrols to the west. Infrastructure may well have been the true treasure of ancient Egypt.

John and Colleen Darnell are a husband-and-wife Egyptologist team. They have presented on the Discovery Channel, History Channel, National Geographic, the Science Channel, and Smithsonian, as well as appeared in National Geographic’s “Lost Treasures of Egypt.”

John is Professor of Egyptology in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at Yale University. His archaeological expeditions in Egypt have been covered by the New York Times. In 2017, his Eastern Desert expedition discovered the earliest monumental hieroglyphic inscription and was named one of the top ten discoveries of the year by Archaeology.

Colleen teaches art history at the University of Hartford and Naugatuck Valley Community College; she has curated a major museum exhibit on Egyptian revival art and design at the Yale Peabody Museum.

[1] Howard Carter and A. C. Mace, The Tomb of Tut-ankh-amen (New York: Cooper Square Publishers, 1963), p. 96.