WCAG Heading

by David Dyer

WCAG Heading

Excerpt taken from The Midnight Watch: A Novel of the Titanic and the SS Californian

Stone walked back to the SS Californian’s rail and looked again towards the south. The three icebergs had drifted astern but he could still see them, stately and tall and brilliantly lit. But he knew not all icebergs were like this. Some were low and grey, and tonight there would be no moon. He wondered how, during the dark hours of the midnight watch, he would able to see them.

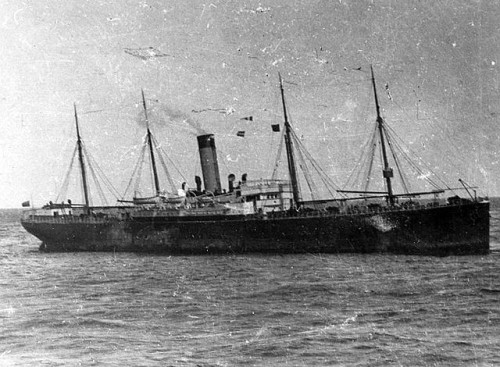

The SS Californian was an ordinary ship, but that’s what Herbert Stone liked most about her. The glamorous new liners of White Star or Cunard were not for him; this modest vessel was good enough. She was middle-aged, middle-sized, and carried commonplace cargoes. Sometimes she also carried passengers – in nineteen old-style, oak-paneled state-rooms – but there had been no bookings for this trip. Instead she had loaded in London textiles, chemicals, machine parts, clothing and general goods, and waiting for her in Boston were a hundred thousand bushels of wheat and corn, a thousand bales of cotton, fifteen hundred tons of Santo Domingo sugar, and other assorted cargoes.

Stone had learned during his training that ships could be spiteful, dangerous things. They could part a mooring rope so that its broken end whoop-whooped through the air like a giant scythe, or take a man’s arm off by dragging him into a winch drum, or break his back by sending him sprawling down a cargo hold. But the SS Californian had done none of these. She was gentle and benign. She had four strong steel masts, and a single slender funnel that glowed salmon-pink and glossy black when the sun shone on it. She rode easy in the Atlantic swells, found her way through the thickest fogs, and her derricks never dropped their cargo. She was a vessel at ease with herself – unpretentious, steady and solid.

Stone was proud to be her second officer and each day he tried to serve his ship as best he could. He was responsible for the navigation charts, making sure they were correct and up to date, and had charge of the twelve-till-four watch. From midday until four o’clock in the afternoon, and from midnight until four o’clock in the morning, he stood watch on the bridge and had command of the ship. The twelve-till-four shift at night was properly called the middle watch, but most sailors knew it as the midnight watch and Stone liked the name: it gave a touch of magic to those four dark hours when the captain and crew slept below and he alone kept them safe.

The midnight watch required vigilance, so he tried always to get some good sleep beforehand. While other officers might visit the saloon after dinner to play cards with the off-duty engineers, or even have a shot of whisky, Stone would retire to his cabin. By eight o’clock he’d be in bed reading, and by nine he would be asleep. That gave him almost three hours’ sleep before his watch began.

But on this cold Sunday night, halfway between London and Boston, he found himself still awake at nine-thirty. He was thinking about the icebergs he’d seen. The lively bounce and throb of his bunk told him that the SS Californian was still steaming at full speed. He thought the captain might have slowed down as darkness fell, given there was ice about, and he was worried they might keep up full speed for the whole night. Stone pictured the men crowded into cramped living quarters low in the ship’s bow – the bosun, the carpenter, the able-bodied seamen, the greasers, trimmers, firemen and donkeymen – lying in their bunks with less than half an inch of steel between their sleeping heads and the black Atlantic hissing past outside.

He flicked on his reading light and took up his book again – Moby-Dick, a gift from his mother. The novel soothed him. He thought no more about icebergs but instead imagined Starbuck aloft, scanning the horizon, handsome in his excellent-fitting skin, radiant with courage and much loved by a noble captain.

David Dyer is the author of The Midnight Watch: A Novel of the Titanic and the Californian and was born and raised in Shellharbour, a small coastal town in New South Wales, Australia. He has served as an officer in the Australian merchant navy and worked as a litigation lawyer at the firm that represented the owners of the Titanic in the aftermath of the disaster. His access to countless documents and artifacts has informed and inspired his work in The Midnight Watch. He lives in central Sydney and Katoomba, a small mountain town in New South Wales.