WCAG Heading

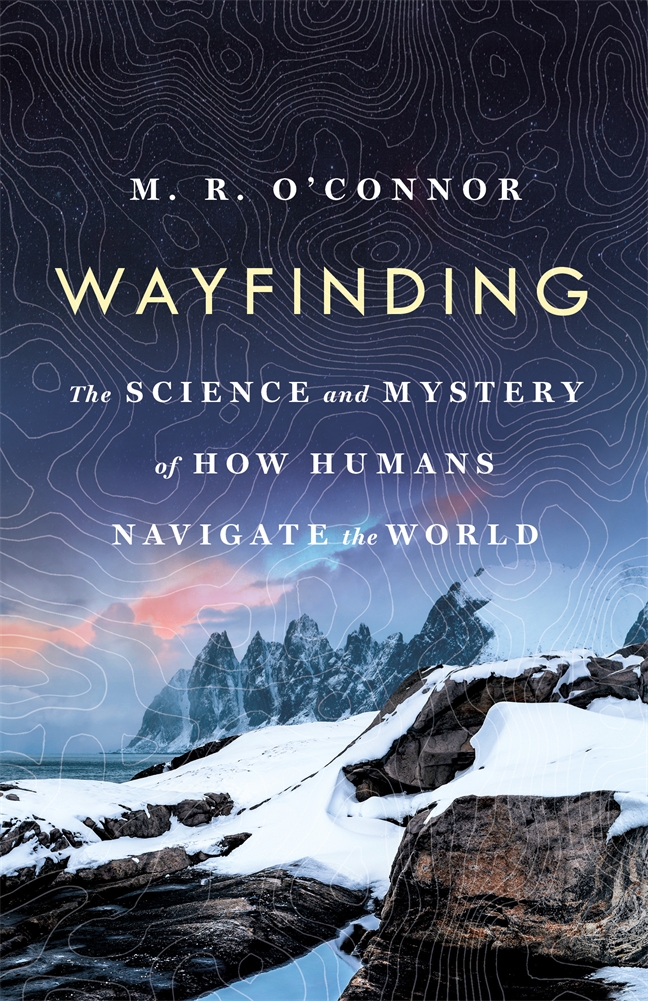

by M. R. O’Connor

Wayfinding is a fascinating look, both sweeping and intimate, at how finding our way makes us human. O’Connor takes readers all over the world, from the frigid Arctic to Australia, talking to master navigators, scientists, and scholars along the way. This captivating journey charts humanity’s profound capacity for wandering, memory, and storytelling, and it explores how exercising the brain through wayfinding can preserve the health of the hippocampus. Keep reading for an excerpt of Wayfinding.

I came to the Arctic because in many ways the landscape has hardly changed in the past four hundred years, or in the thousand years before that. It is one of the last roadless places on earth. Just a few hundred yards outside of town there are no houses, lights, cars, railroads, signage or cell towers, just ice, snow, rocks, and combinations of these elements in jutting and cascading variations. Most of the common navigation skills that will get you by anywhere else are nearly useless in this environment. GPS only lasts as long as a battery, and it can guilelessly lead you along treacherous routes, across faulty sea ice, or into bad weather. The magnetic field tries to pull compass needles downward into the Earth’s crust. Even natural cues are fickle. The stars disappear in summer. In winter, the sun rises in the south and sets in the north. Polaris is a trustless companion for a traveler the farther north you go; above the Arctic Circle, you are north. Landmarks change appearance from season to season as snow gathers or ice melts.

And yet, for thousands of years, the Inuit have thrived in the Arctic as intrepid travelers and hunters. “When adventure does not come to him, the Eskimo goes in search of it,” wrote the twentieth-century anthropologist and writer Jean Malaurie in his classic book The Last Kings of Thule. Malaurie described the first encounters between Europeans like Frobisher and the Inuit as meetings between a “so-called advanced civilization” and an “anarcho-communist society.” But it was also an encounter between two very different ways of experiencing space between those interested in claiming ownership over it for the state and those seeking to know it. The Inuit survived the extreme environment by becoming intimately familiar with its geography. They traveled on foot, dogsled and kayak, visiting hunting and camping places according to the season in the same fashion as their ancestors who migrated to the Arctic from the Bering Strait. Movement and the knowledge it created was necessary for survival, a dramatic endeavor in a place of complex, extreme and fluctuating conditions.

The Arctic archeologist Max Friesen has said that these early inhabitants of the Arctic, who likely arrived around 3200 BCE, probably had a life unlike any other ethnographic group till then with “extremely high mobility levels and active exploration of previously unknown areas.” By 2800 BCE they had reached the central Arctic, and within a few hundred more years, northern Greenland. They likely traveled by foot and kayak but covered vast areas to hunt sea mammals, musk ox and caribou with harpoons and bows and arrows. Around 1000 BCE, they were joined by the Neo-Eskimos, also known as the Thule, who searched for bowhead whales and metal, built large skin boats, and used teams of dogs to pull sleds. They not only shared the Paleoeskimos’ capacity for moving across huge distances, the superseded them: while the Paleoeskimos migrated across the Arctic over several centuries, Friesen believed that some Thule people, direct ancestors of the Inuit, may have crossed it in a single generation.

M.R. O’CONNOR’s reporting has appeared in Foreign Policy, Slate, The Atlantic, Nautilus and The New Yorker. Her work has received support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, The Nation Institute’s Investigative Fund, and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. In 2016 she was a Knight Science Journalism Fellow at MIT. She is the author of Resurrection Science. A graduate of Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism, she lives in Flatbush, Brooklyn.