by Judith Flanders

Log Cabin History

In 1857, the 250th anniversary celebrations of the founding of Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in the Americas, were announced to have been held exactly on the spot where ‘the first log-cabin was built’. In reality, Jamestown’s earliest permanent houses were made of ‘strong boards’ – that is, sawn timber, and the first use of the term log-cabin can be traced back only to 1750. Log cabin history isn’t always as it seems.

For the log cabin was first brought to the new world by settlers from Sweden, where it was a traditional housing style. Many settled on the Delaware and around Maryland’s tidewater region, and it is here that the first contemporary references to houses built of logs appear: a court record in 1662 mentions a ‘loged hows’, while in 1679, a Dutchman recorded a house in what is now New Jersey, built ‘according to the Swedish mode… being nothing else than entire trees, split through the middle… and placed in the form of a square, upon each other.’

By the time William Penn arrived in Pennsylvania, in 1682, there were already numerous log-cabins in the region. Penn’s English followers copied them, believing them to be the indigenous style, as did Scottish and Irish immigrants in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries who saw them on their way south and west. Pennsylvania also drew immigrants from the German-speaking lands where log housing was familiar, before, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, a new group of German immigrants settled in the Hudson and Mohawk valleys. This second wave of immigration grafted German elements on to the earlier Swedish ones, and a third wave of log-house-building immigrants, the Norwegians, who settled in the Midwest, reinforced the basic formula.

As with much new world housing, log-cabins were regarded at the time as temporary and makeshift. They were built by pioneers with little or no cash, out of materials readily to hand. The expectation was that, as soon as the crops from a first harvest on newly cleared land were sold, the cabins would be demolished and replaced with timber-board houses.

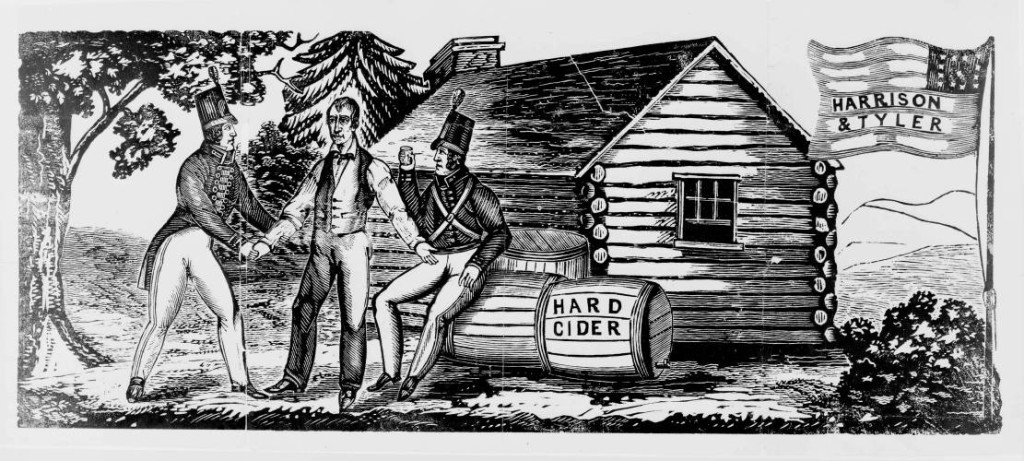

It was only in the 1840s that the log-cabin myth took definitive form. When William Henry Harrison ran for president in 1840, his opponents mocked his supposedly humble background by sneering that he lived in a log-cabin. The canny Harrison embraced the caricature, and his supporters marched with banners and floats depicting log-cabins. Daniel Webster, a long-time politician, couched his endorsement of Harrison in the same terms: ‘I was not myself born in [a log-cabin], but my elder brothers and sisters were – in the cabin… which at the close of the Revolutionary War… my father erected…this humble cabin amid the snow-drifts of New England, [and] strove, by honest labor, to acquire the means for giving to his children a better education, and elevating them to a higher condition than his own’. It’s all there: the frontier, self-sufficiency, the War of Independence, social mobility and of course the log-cabin. Within a year, the symbol had already made an appearance in literature: Natty Bumppo, the hero of James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, although raised by Delaware Indians, lives in ‘a rough cabin of logs’. With this, the log-cabin was well on its way to becoming a symbol of the American spirit itself.

Twenty years later its resonance only increased with the election of Abraham Lincoln, a real log-cabin dweller, to the presidency. With his murder in 1865, the log-cabin came to represent the lost Eden that was pre-Civil War America. Lincoln’s log-cabin birthplace is on show in the Memorial Building at the Lincoln Birthplace Historic Site in Kentucky. Except that it isn’t. The cabin, like most buildings of the type, had been demolished long before Lincoln became famous. Some of the logs may have been reused in a neighboring house. That house, too, was demolished, and another house built, which in turn may or may not have used some of the original logs. It was this third building that in the 1890s toured fairs and exhibitions as Lincoln’s birthplace (and at this point some of the logs from that already-compromised building also vanished), before being installed at the Birthplace site. From such fairs and exhibitions, the log-cabin symbol seeped into the everyday life of twentieth-century suburban domesticity: 1916 saw the production of Lincoln Logs, children’s building blocks in the shape of logs (designed by the son of modernist architect Frank Lloyd Wright); and tins of Log-cabin maple syrup, named in the 1880s for Lincoln’s birthplace, bore a picture of a log-cabin at least until the 1960s.

Other symbols of Americana – the spinning-wheel and the patchwork quilt – are similarly mythological. In 1858, Longfellow’s The Courtship of Miles Standish presents the prototypical Puritan maiden, Priscilla Mullins, sitting ‘beside her wheel’, but in reality, in the early days of the colony, only about one family in six owned a spinning-wheel. Even fewer wove. Most cloth, from the earliest days, was purchased. Spinning was simply not time-efficient: one wheel could produce only enough yarn to knit an average family’s stockings. It was the Revolution first, then the War of 1812, with their boycotts of British goods, that turned spinning and weaving into activities with patriotic resonance. Thereafter homespun fabrics came to signify the self-sufficiency of the new nation. By the 1820s, northern citizens were once more relying on industrially manufactured textiles, but homespun survived in the south, as slave labor made its production more viable, and in the west, where a low- to no-cash economy made it essential.

The substantial proportion of the population which relied on homespun therefore suggests that the supposedly common homemade patchwork quilt must in reality have been a rare object before the nineteenth century. Patchwork is a product of surplus, of textiles that are abundant enough that large remnants are routinely available – large enough and routinely enough that they can be used to make another item entirely. If the output of a single spinning-wheel only kept a family in stockings, how much more work was needed to produce a family’s clothes, and have more left over for scrap? In Britain quilts began to be seen in quantity once cheaper textiles from India became available in the eighteenth century. But in the USA, throughout the nineteenth century, clothing for everyone except the minority of cash-paid workers continued to be square-cut, to utilize every scrap of valuable material. Patchwork was not a product of pioneer life, but of the industrial world.

Communal quilting-bees, too, if not entirely a myth, are nevertheless an elaboration of reality. The bulk of the work for any quilt – the cutting of the squares, their stitching, lining, preparing the batting – was done at home alone, or by several family members working independently on different elements. Only the quilting, the final stage, was a joint effort. A quilting frame took most of of a room: it was generally stored in an outbuilding, or shared among several families or a community. The purpose of the bee was to get the job done as quickly as possible so that the frame could be returned to its storage place and daily life resumed in the main room. Although there was certainly a party element to the event – food was provided, and for those who lived in sparsely populated districts, any sort of companionship was festive – sociability was not the motivating factor.

JUDITH FLANDERS is an international bestselling author and one of the foremost social historians of the Victorian era. Her book most recent book THE MAKING OF HOME The 500-Year Story of How Our Houses Became Our Homes published this week, September 9th and INSIDE THE VISTORIAN HOME was shortlisted for the British Book Awards History Book of the Year. Judith is a frequent contributor to the Daily Telegraph, Guardian, Spectator, and the Times Literary Supplement. She lives in London.