by Edmund Richardson

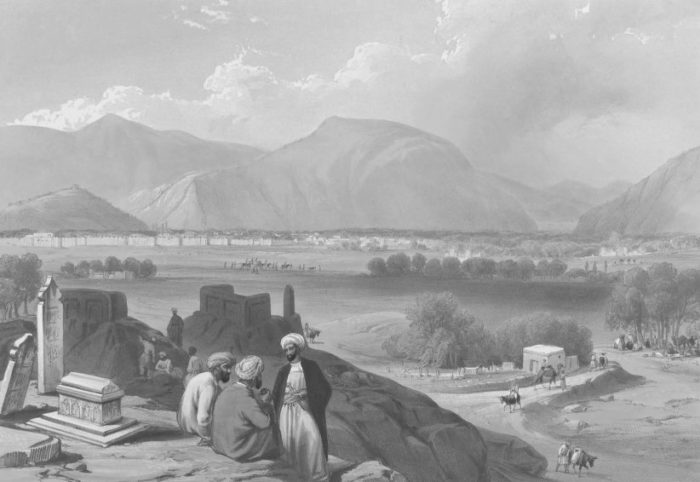

Beneath the plains of Afghanistan lie the remains of a fabulous city: Alexandria Beneath the Mountains, founded by Alexander the Great. For centuries, it was a meeting point of East and West. Then it vanished. In 1833, it was discovered in Afghanistan by the unlikeliest person imaginable: Charles Masson, deserter, doctor, archaeologist, spy, and the greatest of nineteenth-century travelers. The King’s Shadow follows Masson’s astounding journey through nineteenth-century India and Afghanistan, a world of espionage and dreamers, murder, betrayal, and boundless hope. Read an excerpt below.

In the winter months the people of Kabul retreated indoors and wrapped themselves in heavy sheepskins. Wine froze, and ‘copper vessels burst during the night.’ In spite of the bitter cold, Masson was happy. No one knew whether he was a traveler, a spy or a madman, and no one cared. ‘There are few places where a stranger so soon feels himself at home, and becomes familiar with all classes, as at Kabul. There can be none where all’, he wrote, ‘so much exert themselves to promote his satisfaction and amusement. He must not be unhappy. To avow himself so would be, he is told, a reproach upon the hospitality of his hosts and entertainers. I had not been a month in Kabul before I had become acquainted with I know not how many people; and become a visitor at their houses.’

Masson spent his days wandering Kabul. The city’s bazaar was one of the wonders of Asia. Mohan Lal, an Indian scholar who traveled with Alexander Burnes (and kept him from being killed more than a few times), was not easily impressed: he had grown up in Delhi. But Kabul’s bazaar left him awestruck. ‘The parts of the bazaar which are arched over exceed anything the imagination can picture. The shops rise over each other, in steps glittering in tinsel splendor, till, from the effect of elevation, the whole fades into a confused and twinkling mass, like stars shining through clouds.’ As Masson worked his way from one stall to another, examining the winter displays of ‘wild ducks and sparrows’, he had no idea that he was being watched.

The East India Company had a spy hard at work in Kabul, and he kept a very close eye on the comings and goings of strangers. Soon after Masson returned from Bamiyan, the spy reported that ‘whilst seated in a shop in the bazaar, a man passed by me, who had the appearance of a European, grey eyes, red beard, with the hair of his head close cut. He had no stockings nor shoes, a green cap was on his head, and a fakir or dervish drinking cup over his shoulder. He did not, however, resemble a dervish much, and appeared to be staring at everything with the curiosity of a stranger. I observed to the owner of the shop, who had been in Russia, that the man was a Russian; he replied, “Yes, and all who have seen him say so; but he is an Afghan.” The man was then lost in the crowd, but a few days later I saw him again, and accosted him, but got no answer, and he walked away very fast.’

The spy’s report was soon on its way over the mountains to India. He resolved not to let the red-haired stranger slip away so easily the next time they met.

Masson, meanwhile, spent his evenings reading and sketching out Alexander’s route. Deciding to find a lost city is easy but, Masson was realising, knowing where to begin was much harder.

In 1812, when he was looking for Petra, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt simply asked for directions.

Burckhardt wandered through the Middle East in disguise, calling himself Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn Abdallah, and asking everyone he met about Petra, the ancient trading city in the mountains of Jordan. Eventually, he was told about a path leading into a deep, hidden valley, near a tomb said to be that of the Prophet Aaron. Burckhardt followed the path. Sandstone cliffs rose higher and higher on either side. The dust clung to his clothes. Then, at last, Petra opened up before him:

It seems no work of Man’s creative hand,

by labour wrought as wavering fancy planned;

But from the rock as if by magic grown,

eternal, silent, beautiful, alone…

A rose-red city half as old as time.

When he returned to Europe, Burckhardt’s discovery of Petra made him a household name. In Jordan, it was met with bemusement: Burckhardt’s ‘discovery’ had been common knowledge for centuries. Sultan Baibars of Egypt had visited Petra in the thirteenth century, over 500 years earlier.

Masson knew that finding one of Alexander’s lost cities would not be so straightforward. Most of the Alexandrias are truly lost: even today, our best guesses for their locations are little more than pins stuck in a map. ‘In most cases the vital factors which would enable us to identify this or that ancient site with a modern locality simply do not exist, and to debate the preference,’ Peter Fraser recently wrote, ‘is fruitless. In almost every case any attempt to be more precise than the ancient source leads to a dead end.’ But, sitting by the fire in Kabul, wrapped up in a sheepskin, Masson soon knew which Alexandria he was looking for.

In 329 BC, Alexander stood at the foot of the Hindu Kush mountains, looking east into an unknown world. He and his army had traveled further than any Greeks before them. They had won greater victories than the heroes of old. The ends of the earth were close at hand. ‘Alexander led his army towards Mount Caucasus,’ wrote Arrian, ‘and there, he founded a city, and named it Alexandria. Then, after offering sacrifices to all of the gods he was accustomed to sacrifice to, he led his army across Mount Caucasus.’ Three thousand of his men settled there: soldiers too old or too sick to carry on. Like Masson, they found a new home in a strange land.

After Alexander’s death, Alexandria beneath the Mountains, as the city came to be known, thrived for centuries. At the edge of Alexander’s empire, it was left to govern itself. A thousand years after Alexander’s death, a Chinese traveler wrote fondly of it. Nestled beneath the Hindu Kush, rich in fruit trees, it still inspired awe. Then, it slowly faded from memory.

Masson knew that Alexandria beneath the Mountains might have been a city of wonder. Alexandria in Egypt, the most famous of Alexander’s cities, was one of the glories of the ancient world: a cultural and intellectual crossroads like no other, where scholars, traders, artists and writers developed new ways of understanding the world. In Afghanistan, might there be ancient theatres lying hidden? Temples to strange gods? Palaces of unknown kings? Anything was possible. Not all lost cities are real (no one is about to find Atlantis), but this one was. Somewhere in Afghanistan, hidden by time, by dust and snow, lay the remains of a fabulous city.

For over 1,000 years, Afghanistan had been a blank space in western knowledge. In 1833, scholars thought Alexandria beneath the Mountains was underneath modern-day Kandahar, around 300 miles from Kabul. Masson knew they were wrong: that relied on Alexander’s army crossing Afghanistan from north to south, on foot, in only ten days. Every blister on his feet told him this was impossible. The city had to be much closer to Kabul. But where?

The ancient historians of Alexander were no help: a more untrustworthy crew has rarely been assembled. The most reliable of them, Arrian, never set foot in Afghanistan. His narrative is full of weird portents and dubious anecdotes (if his battles seem less than exciting, perhaps he might offer an interlude with Alexander and the Amazons?). He devotes only a few lines to the foundation of Alexandria beneath the Mountains. He spends much longer on the story of an Afghan city which it would be brave to seek: Nysa.

When Alexander’s army appeared before the walls of Nysa, Arrian says, the people sent a delegation out to meet him, dressed in their finest clothes. ‘When they entered Alexander’s tent, they found him sitting there, covered in dust and weary from travel. He was still in his armor: a helmet was on his head, and a spear was in his hand. For a moment, no one spoke, then the people of Nysa fell on their faces before him.’ They told Alexander their story. Their city had been built by none other than Dionysus, the Greek god of wine and misrule himself. ‘On his way home from India, he founded this city as a memorial of his long journey, and his many victories. The men he settled here were those of his companions, and his priests, who could go no further. He and you are alike: for, after all, you have founded Alexandria beneath the Mountains and Alexandria in Egypt, and many other cities too. And you will go on to found still more. Soon, indeed, you will have accomplished more than Dionysus himself.’

This was the only evidence Masson had to work with. It was not enough.

Copyright © 2022 by Edmund Richardson.

Edmund Richardson is Professor of Classics at Durham University, UK. He has published Classical Victorians: Scholars, Scoundrels and Generals in Pursuit of Antiquity (2013), and was named one of the BBC/AHRC New Generation Thinkers in 2016.