by Catharine Arnold

Revisiting the American soldiers aboard the USS Leviathan, Catharine Arnold discusses the dark, cramped, and overall ‘hellish’ conditions as the Spanish flu wreaked havoc on the ship.

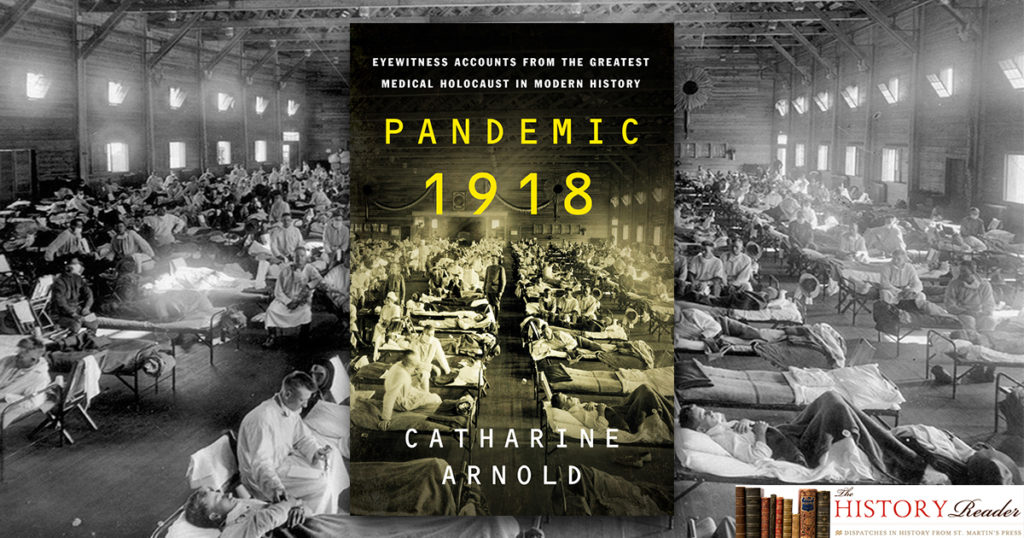

This photograph is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Although the United States was in the grip of the Spanish flu epidemic, the army still insisted that there was no reason for alarm. On 4 October, while the Leviathan was at sea, Brigadier General Francis A. Winter of the American Expeditionary Force told the press that everything was under control and there was no reason to fear an epidemic. ‘About 50 deaths only have occurred at sea since we first began to transport troops,’ he claimed, eager to maintain morale by assuaging fears.

The Leviathan was overcrowded, although not as overcrowded as on previous voyages, when she had carried 11,000 soldiers. The ship originally had a capacity of 6,800 passengers, but this capacity had been increased by over half. The US government referred to this process as ‘intensive loading’ rather than the 50 percent overload it really was. Conditions were cramped, with the men confined to quarters, huge steel rooms each holding 400 bunks. There was nothing for them to do apart from lie on their bunks or play cards, and the portholes, painted deep black, were clamped tight shut at night to avoid the enemy submarines spotting light shining from them.

Rules and prohibitions were precise and strictly enforced. A lighted cigarette upon a dark deck high in the air might be seen a half a mile at sea, enabling an enemy submarine to radio a lookout warning to another ‘sub’ lying in wait ahead. Those pests of the deep generally worked in pairs. To show how strict the blackout regulations were, one man was court-martialled and sent to prison, an officer was court-martialled and reduced, and an army chaplain, who was assisting the chaplain of the ship in administering to the dying, was threatened with court-martial because he had opened a port slightly in response to a dying soldier’s request for air. As a consequence of the blackout regulations, life on the Leviathan was spent, for the most part, in conditions of near darkness.

As if to add further degrees of hellishness, the ineffectual ventilation system made little impact on the reek of sweat, and the noise levels in the all-steel structure approached pandemonium, with thousands of footsteps and shouts and cries echoing back and forth throughout the steel walls, stairs and passageways.

And then the nightmare was unleashed. Despite the fact that 120 sick men had been removed from the Leviathan before sailing, Spanish flu symptoms manifested themselves within less than twenty-four hours of leaving New York harbour. To deter the spread of the disease, the troops were quarantined, sent to mess in separate groups at mealtimes to avoid the risk of infection, and confined to quarters. At first, they meekly accepted this ruling in the belief that the quarantine was keeping them safe.

Soon every bunk in the sickbay was occupied and other men were lying sick in regular quarters. They were all marked with the deadly symptoms of the Spanish Lady, a euphemism for the killer flu: coughing, shivering, delirium and haemorrhaging. The nurses began to fall sick too. Colonel Gibson, commander of the 57th Pioneer Infantry Regiment, recalled that:

The ship was packed. Conditions were such that the influenza could breed and multiply with extraordinary swiftness. The number of sick increased rapidly. Washington was apprised of the situation, but the call for men for the Allied armies was so great that we must go on at any cost. Doctors and nurses were stricken. Every available doctor and nurse was utilized to the limit of endurance.

By the end of the first day, 700 troops were sick and the Leviathan was undergoing a full-blown epidemic. The horrific truth became apparent: the Spanish Lady had boarded the vessel with the doughboys and nurses bound for France. There was an urgent need to separate the sick men from the healthy to stop the disease spreading. Arrangements were made to put the overflow patients from the sickbay into 200 bunks in F Room, Section 3, port side. Within minutes, F Room was filled with sick men from the decks. Next, the healthy men of E Room, Section 2, starboard side, surrendered their bunks to the sick and were sent down to H-8. This room had been previously condemned as unfit for human habitation as it was poorly ventilated. By 3 October, the port side of E Room, Section 2, which held 463 bunks, had been commandeered for the sick and the occupants were sent off to find space in the ship wherever they could. In a grim game of musical chairs, three sick soldiers evicted four healthy men. The top bunk of the four-bunk stack could not be used by the sick, as the nurses were unable to climb up and the sick could not climb down. During this horrific voyage the army nurses were described by the ship’s historian as ‘ministering angels during that dreadful scourge. They were brave American girls who had left home and comfort in order to undergo peril and sacrifice abroad.’

The number of sick increased, with a high proportion of patients developing pneumonia. There was no room on the Leviathan for 2,000 sick and recovering men, and no way to care for such a high number of patients. Those doctors and nurses who had not succumbed themselves devised a system of separating the sick from the very sick. All patients were discharged from the sick bays and sent back to their units the minute their temperatures dropped to 99°.

It was impossible to determine just how many men were sick. Many remained in their bunks, unable to move and seek help. Rough seas made seasickness an additional complication. Young men who had never experienced seasickness before presented themselves to the sickbay and were admitted by inexperienced medics. Meanwhile, a stream of men with genuine flu symptoms were turned away for lack of space, and, so delirious that they were unable to find their way back to their own quarters, they simply laid themselves down on the deck. Others walked into the sickbay unchallenged and occupied any empty bunks they could find.

© Copyright Catharine Arnold 2020

Catharine Arnold read English at Girton College, Cambridge and holds a further degree in psychology. A journalist, academic, and popular historian, her previous books include The Sexual History of London, Necropolis, and Bedlam.