by Steven Saylor

Psssst! Have you heard about Elagabalus? They say he invented the world’s first whoopee cushion. No, really! I’m pretty sure I heard Mary Beard say that.

They also say he was as gay as America’s Next Drag Superstar, and as crazy as a loon. He was such a phallomaniac he combed the whole empire to locate the man with the largest you-know-what. But he married for love—another man, of course, a charioteer. But wait, they also say he married a Vestal virgin. How would that even work?

Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1888).This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

His reign was brief. The Romans had enough of him in short order, or at least the Praetorian Guards did, and Elagabalus came to a very nasty end, along with his charioteer husband and his power-mad mom.

You may wonder: how in Hades did a Roman emperor get a name like Elagabalus, anyway?

In fact, in his own lifetime, he was never called Elagabalus; that was the name of the sun god he imported to Rome from his native province of Syria. It was hostile Roman historians of a later generation who stuck him with that name, making him out to sound as foreign, outlandish, and downright strange as possible. Those same ancient historians, sucking up to his successors, went wild making up “facts” about the teen emperor, cranking out an orgy of salacious gossip, malicious slander, and fake news that no modern historian takes seriously.

But gossip has a way of sticking in people’s heads—the wilder the better. And so, all these centuries later, textbooks still call him “Elagabalus,” and reputable historians on TV, with a nod and a wink, repeat the same slanders and nonsense.

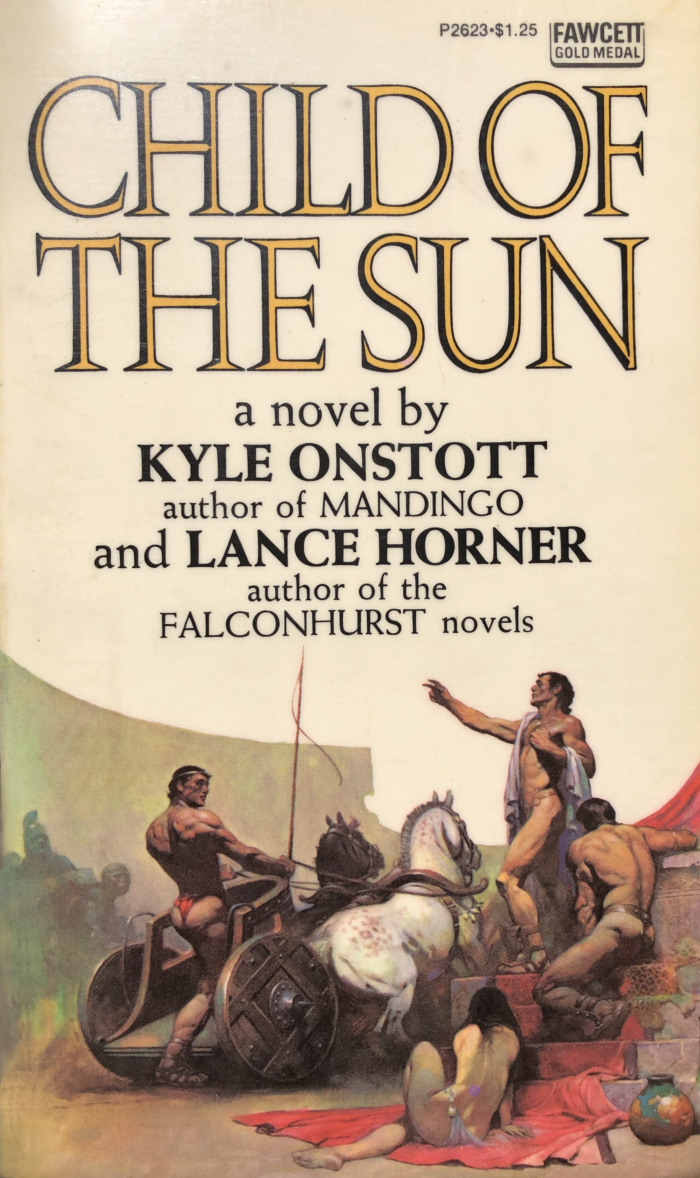

I first encountered Elagabalus when I was a teenager myself, growing up in a small town in Texas (think Last Picture Show). Somehow I got my sweaty hands on a paperback novel called Child of the Sun, a book so trashy it took two authors to write it (Kyle Onstott and Lance Horner). I could tell it must be a gay novel because of the Frank Frazetta artwork on the cover, in which three scantily-clad muscle men totally overshadow the gratuitous female. The authors skipped the weirder parts of the Elagabalus legend (like smothering a roomful of dinner guests with a deluge of rose petals, a scene immortalized in paint by Alma-Tadema). They concentrated on the sexy parts, in graphic detail, and played up the romance. The teen emperor finds true love with the hunky charioteer, but alas, they still meet a horrible fate.

Child of the Sun made a huge impression on me, in the way novels do when the reader is an impressionable and highly imaginative teenager. I suspected even then that someday I might write my own fictional version of Elagabalus.

In college, I studied Roman history, and paid especially close attention to what modern historians had to say about Elagabalus. Clearly, the ancient sources were not to be trusted. Nonetheless, in the 1700s, Edward Gibbon in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire had a jolly time denouncing the disgusting immorality and decadence of the teen emperor. Elagabalophiles of the twentieth century took the opposite tack, casting him as a queer martyr, embracing his reputed homosexuality—or perhaps transgender identity, since one source claims the teen emperor desired or even attempted an ancient-world gender-reassignment procedure.

Despite the scanty facts about him and the briefness of his reign (June A.D. 218 to March A.D. 222, less than four years), Elagabalus has accumulated a considerable Nachleben. That’s a German word historians use to describe the cultural afterlife of a historical person and the transmutation of factuality into myth via poetry, opera, theater, painting, novels, etc. Much of this is detailed in a fine book by Martijn Icks, published in England as Images of Elagabalus but in the U.S. pruriently entitled The Crimes of Elagabalus: The Life and Legacy of Rome’s Decadent Boy Emperor.

In fact, what can actually, verifiably be known about Elagabalus? A few years ago, a Cambridge-education Spaniard named Leonardo de Arrizabalaga y Prado (another mouthful!) published a truly remarkable book titled The Emperor Elagabalus: Fact or Fiction?, in which he devised a system for evaluating the credibility of every morsel of information about the teen emperor. Under de Arrizabalaga y Prado’s keen and ruthless gaze, the story of Elagabalus is exposed as nothing more than smoke and mirrors.

The Emperor Elagabalus: Fact or Fiction? was not well received by the Classical establishment. The reaction pretty much boiled down to: “If you’re going to be that nit-picking, then we’ll have to admit that just about all of what we call ‘history’ is really fiction to start with, and where will that leave us?” Out of a job, presumably.

But humanity cannot live on epistemology alone; we need stories. Even Arrizabalaga y Prado is said to be working on a novel about Elagabalus, though I can’t imagine what scraps of material are left on his workshop floor that could be stitched into anything as capacious as a novel.

As I said earlier, from the moment I finished my (first) reading of Child of the Sun all those many years ago, I’ve had an itch to write my own version of Elagabalus. The opportunity at last arrived with Dominus, my latest novel. Dominus completes the trilogy begun by Roma and Empire, a family saga that spans the history of Rome from prehistoric trading post to the reign of Constantine the Great. Constantine was the Roman emperor who rejected the old religion and embraced Christianity. He also spurned the city of Rome and moved the real seat of power to a new capital named after himself, Constantinople.

Like Constantine, Elagabalus was a religious revolutionary. He tried to totally reorganize the state religion, elevating his Syrian sun god to the top spot, even above Jupiter. Perhaps he was ahead of his time. Unlike Constantine, he failed, spectacularly and in short order. His religious radicalism, more than anything to do with his personal life, may have been the true “crime” that led to his gruesome end.

Nonetheless, when the father and son of my fictional dynasty in Dominus are summoned to the imperial palace and meet Elagabalus in the flesh, they get the shock of their lives. Writing that scene was a guilty pleasure for the author, because when they step into the room, and approach the teen emperor…

But I will say no more, because perhaps you’d like to lay hands on Dominus and read that scene yourself.

Oh, and his real name, by the way, was Varius Avitus Bassianus. That’s another mouthful.

Steven Saylor is the author of the long running Roma Sub Rosa series featuring Gordianus the Finder, as well as the New York Times bestselling novel, Roma and its follow-up, Empire. He has appeared as an on-air expert on Roman history and life on The History Channel. Saylor was born in Texas and graduated with high honors from The University of Texas at Austin, where he studied history and classics. He divides his time between Berkeley, California, and Austin, Texas.