by Jefferson Morley

I started out as a newspaper reporter, which led to investigative reporting, which led me to writing history. I think of my genre as investigative history, which seeks to combine the punch of a news story with the wisdom of the long view. The trick—or should I say art—is finding genuinely new material, a matter of serendipity, persistence, and enterprise. All three came together in the writing of Scorpions’ Dance.

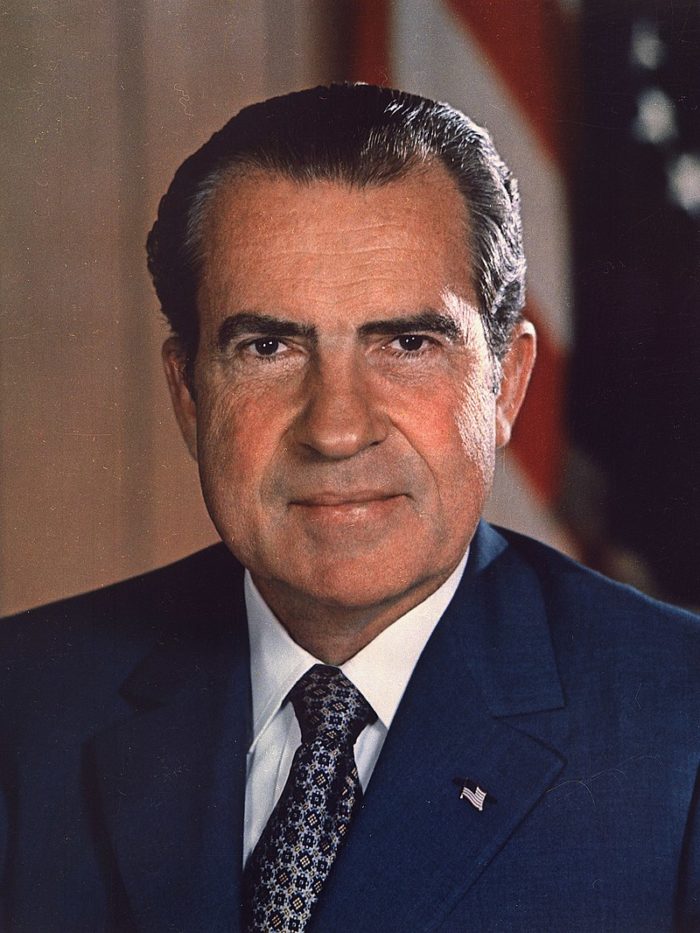

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

It all started in 2009 when I came across nixontapes.org, a site created by Professor Luke Nichter of Texas A&M University. A historian, Nichter had collected all of the White House tapes generated by President Richard Nixon, converted them to audio files, annotated them with Nixon’s daily calendar, and organized them by primary participants. It was a marvelous historical resource, so when I saw the name “Richard M. Helms,” I clicked.

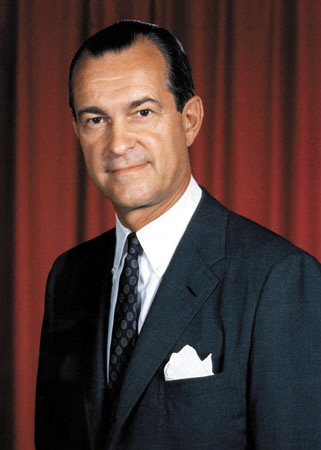

Helms, who served as CIA director from 1966 to 1973, was a longtime friend of Winston Scott, the agency’s top man in Mexico in the 1960s, and the subject of my first book Our Man in Mexico.

Nichter’s introduction tingled my reporting antennae: “The collection below marks the first time that recordings of private meetings between a director of the CIA and any president have ever been made public,” he wrote. “There’s a story here,” I thought, and, thirteen years later, that story turned out to be Scorpions’ Dance.

As I listened to the conversations between Nixon and Helms, I heard a paranoid president and a supple spymaster: voices of power, intimations of intrigue, reverberations of history. Here was a character and plot come alive.

Nixon, the anxious intelligent West Coast striver, parried with Helms, the gentlemanly spy from Philadelphia’s Main Line. The first conversation was a spat—a shouting match, really—in which Nixon attacked the CIA. The second was chummy, in which the spymaster flattered his boss. A third conversation captured the menacing president pressing his obdurate intelligence chief for some of his agency’s darkest secrets. Another disclosed a friendly chat between Nixon and Helms just hours before the arrest of five burglars, at the Watergate complex—the event that toppled both men from positions of supreme power into notoriety and disgrace.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

But the tapes themselves, I discovered, were not enough for a book. To make sense of Nixon and Helms’ complex but opaque dealings, the reader would need the context of their relationship going back to the day they first met. And telling that story, in a compelling way, required more such genuinely new material. It was only a decade later, when I got a contract to write a book about Watergate, that I began to build out the 11 conversations between Nixon as the spine for the story of the rise and fall of these two Machiavellian masters.

I already had another batch of original archival material—mostly as a matter of sheer luck. A Miami man named Randy Flick had contacted me years before to tell me that he had inherited a box of papers from his father-in-law, a former CIA agent named Tony Sforza. In January 2019, I met with Flick and we agreed that I would write an article about the papers as a way of calling attention to the book he wanted to write. Two months later, Flick’s wife called me to say Randy had died of a heart attack. Because her husband had trusted me, she said she would be glad to show me his material.

I went back to Miami and found myself looking at an extraordinary collection of correspondence, photographs, and memoranda compiled by a CIA hit man who worked for Helms. This was the rarest of finds: authentic evidence of CIA covert operations, not concealed or obfuscated by the laws of official secrecy. The Tony Sforza papers added new deadly detail to the story of how Nixon ordered Helms to carry out an assassination in Chile in the 1970s.

Here was a medal that Helms gave to Sforza in 1962. Here was the picture of the body of an Argentine revolutionary killed on a lethal mission in 1964. Here were the fake identification papers that Sforza used while running the CIA’s manhunt for revolutionary Che Guevara in Bolivia in 1966. Here was a letter he wrote to his wife while pursuing Chilean general Rene Schneider who died in a hail of gunfire in 1970. This material, like the White House tapes, embodied the reality of how Nixon and Helms wielded power.

I found another rich vein of material in the footnotes of Dirty Tricks, documentarian Shane O’Sullivan’s 2019 book about the Watergate affair. In passing, O’Sullivan mentioned that Earl Silbert, the first Justice Department prosecutor assigned to the Watergate case, had recently donated his diary from that time to the National Archives. No one else had ever written about it. I found a PDF copy on the Archives website and was again plunged into the immediacy of Nixon and Helms’ world.

Silbert was a lawyer, not a writer. In the diary, mostly dictated late at night on weekends, the prosecutor sought to make sense of the crime that baffled and intrigued all of Washington. He was probing the crimes of Nixon and his men while conferring with Helms, who had to explain the CIA background of five of the seven burglars. The artlessness—and cluelessness—of Silbert’s narrative actually made it more credible to me. His damning summary of his dealings with Helms, passed on to Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox, was the ultimate insider’s view of how the CIA director deflected the Watergate investigators away from the agency’s hidden hand.

There were other finds in my research. Thanks to Christopher Buckley, I got access to the correspondence of his father, columnist William F. Buckley, with Howard Hunt, the burglar in chief who was pals with Helms. In declassified records related to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, I found the story of how Helms had previously duped investigators interested in his agency’s shadowy role.

In every case, it was the human detail of such original material that enriched and propelled the narrative. The conversational voice, the unguarded observation, the confidential letter, the declassified secret—these are the fuel of investigative history.

Jefferson Morley is a journalist and editor who has worked in Washington journalism for over thirty years, fifteen of which were spent as an editor and reporter at The Washington Post. The author of Our Man in Mexico, a biography of the CIA’s Mexico City station chief Winston Scott, Morley has written about intelligence, military, and political subjects for Salon, The Atlantic, and The Intercept, among others. He is the editor of JFK Facts, a blog. He lives in Washington, DC.