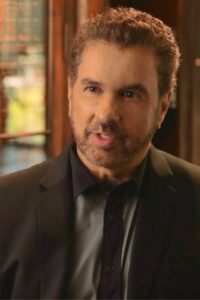

by J. Randy Taraborrelli

New York Times bestselling author J. Randy Taraborrelli shares with The History Reader how John F. Kennedy (JFK) became a stronger leader after publicly apologizing for the Bay of Pigs disaster, which caused the president global humiliation. Read on to discover the education of JFK.

When John F. Kennedy was elected president in 1960, he inherited more than a Cold War. He inherited a national security establishment that believed it knew better than any civilian, especially a 43-year-old with a Harvard accent and chronic back pain. The CIA, the Joint Chiefs, and the Pentagon had all operated with near-total autonomy under Eisenhower. They didn’t expect to be second-guessed by someone they saw as young, untested, and maybe a little too intellectual for his own good. From the moment JFK took office, he was caught in a tug-of-war between his own instincts and the forceful advice of these men around him. It nearly cost him everything.

The Bay of Pigs was the first wake-up call.

In April 1961, Jack Kennedy approved a CIA-led plan to invade Cuba and overthrow Fidel Castro. The operation had been developed under Eisenhower, refined by the CIA, and signed off by the military brass. Kennedy was uneasy about it from the beginning. He thought the plan was sloppy and overly optimistic, but the experts insisted it would be quick and clean. Therefore, he reluctantly gave it the green light.

It was a disaster. The Cuban exiles were slaughtered or captured, and Castro emerged even stronger. JFK ended up humiliated on the world stage.

Bobby urged Kennedy to take responsibility. “You have to own up to it,” he told him. “People forgive when you admit mistakes.”

Jackie, on the other hand, was suspicious. Her mother, Janet Auchincloss, wrote to a close friend:

Last night Jacqueline told [me] – “Not one goddamn thing should come out of the President’s mouth in terms of admitting anything in relation to it [Cuba].”

The patriarch, Joe Kennedy, agreed: “The president does not apologize,” he roared. “He’s the goddamn president!”

In the end, JFK sided with Bobby. “There’s an old saying,” he told reporters at a State Department press conference four days later, “that victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan. I am the responsible officer of this government.” He fell on his sword and did so humbly. He didn’t blame the previous Eisenhower administration or lament what he had inherited from it. What happened under his watch was his fault, he said, and that was the end of it.

While writing JFK: Public Private Secret, I spent a lot of time studying how that single failure shaped pretty much everything that came next. What I discovered was that the Bay of Pigs broke Kennedy’s trust, but it also built his backbone.

Within months, JFK fired CIA Director Allen Dulles and reshuffled the intelligence leadership. He stopped deferring to titles and medals. He started asking better questions. Most importantly, he stopped being impressed by resumes and started being guided by conscience.

So when the next crisis hit, he was ready.

In October 1962, American spy planes discovered Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba, just ninety miles from Florida. The Joint Chiefs and many in the CIA immediately pushed for airstrikes, followed by an invasion. It was Bay of Pigs 2.0, and this time with nuclear consequences.

But Kennedy had changed. He slowed things down. He insisted on hearing every side. He formed a smaller advisory group called ExComm and demanded honest debate, not groupthink. The loudest voices in the room called for action. But JFK knew what would happen if a single shot were fired: Khrushchev would have to respond, and the world would descend into nuclear war.

“There was no waking or sleeping,” I quote Jackie as having recalled. “No day or night.”

Instead of striking, JFK ordered a naval blockade. It was firm but not aggressive. Importantly, it bought time.

Behind the scenes, JFK opened backchannels to Moscow. He figured Khrushchev wasn’t just an enemy–he was also a man who wanted to avoid annihilation.

It worked. The Soviets agreed to withdraw their missiles. The U.S. quietly agreed not to invade Cuba and also to remove American missiles from Turkey.

Crisis averted. But more importantly, precedent shattered.

In JFK: Public Private Secret, readers will see how close Kennedy came to ignoring his instincts. Again. Most of the men in the room wanted escalation. But this time, JFK stood his ground. “The military are mad,” he confided. “They think in terms of military victory, not human survival.”

It wasn’t just JFK’s brilliance that saved the world. It was the humility of a man who knew what it felt like to get it wrong and not want to make that same mistake again.

As I researched this part of my book, I couldn’t help but wonder: if Kennedy had lived, how far would he have pulled away from Cold War thinking? Would he have drawn down in Vietnam? (In fact, as I wrote, he did have a plan to de-escalate things there.) Could he have reshaped American foreign policy? We’ll never know.

But what we do know is that by the time he and Jackie left for Dallas in November 1963, JFK was no longer the man who nodded politely in briefings and deferred to the so-called experts. He had been burned, and unlike so many others in power, he actually learned from it.

That’s not always part of the Camelot myth. But it should be.

J. RANDY TARABORRELLI is the acclaimed author of numerous New York Times bestsellers about the Kennedys, including Jackie, Ethel, Joan: Women of Camelot, adapted as a miniseries by NBC, and The Kennedys – After Camelot, adapted for television by Reelz. His other bestselling works include The Kennedy Heirs and Jackie, Janet & Lee. His most recent book, Jackie: Public, Private, Secret, debuted at No. 3 on the New York Times bestseller list. Taraborrelli is currently adapting both Jackie: Public, Private, Secret and JFK: Public, Private, Secret for television.