dd

by Chris Wimmer

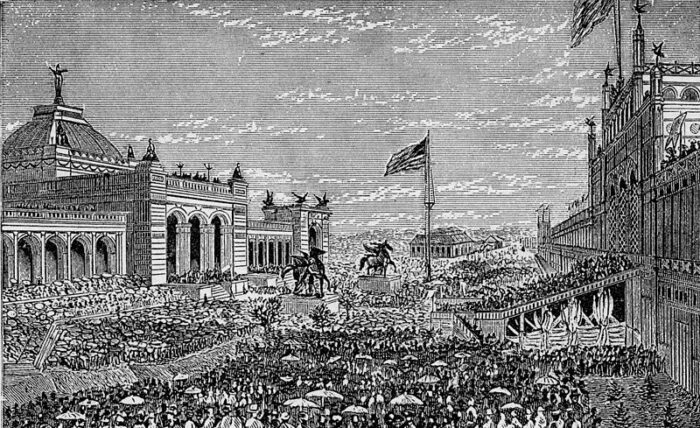

The first World’s Fair on American soil ran from May 10 to November 10, 1876. Millions of visitors flocked to Philadelphia to see the show. But two months before it ended, it nearly went up in smoke.

In early October of 1871, a small fire started in or near a barn that belonged to the O’Leary family on the southwest side of Chicago. Thanks to the hot, dry, windy conditions, the blaze built into a roaring inferno. Over the course of three days, the fire destroyed three square miles of the city. It killed 300 people, burned 17,000 structures, and left 100,000 people homeless. It became known as the Great Chicago Fire for good reason. One year later, a similar fire ravaged Boston. It started downtown near the corner of Summer Street and Kingston Street on a Saturday evening. It tore through sixty-five acres of the city and destroyed nearly eight hundred buildings.

After two devastating events in two major cities, the organizers of the Centennial International Exposition in Philadelphia—the first World’s Fair on American soil—knew their greatest fear was fire. The city of Philadelphia outlawed the construction of wooden structures leading up to the Centennial celebrations, but it didn’t have the resources to fully enforce the edict. Nearly every street and alley was packed with theatres, saloons, brothels, beer gardens, hotels, restaurants, and shops of every description. Everyone knew that millions of tourists would visit the World’s Fair in the spring, summer, and fall of 1876. There was a fortune to be made, and Elm Avenue was ground zero.

Elm Avenue was near the main entrance to the exposition and it showcased the grandeur and the fears of the organizers of the World’s Fair. Visitors could gaze at the magnificent spectacle of the acres of buildings that housed the exhibits, and they could also step into one of the dozens of shoddily constructed businesses that sprang up to capitalize on the expo. Some called Elm Avenue, “Centennial City.” Others called it, “Shantytown.”

On September 9, 1876, Shantytown started to burn.

A few minutes after 4 p.m., a cook in the Broadway Oyster House poured gasoline into a tank that was connected to a stove. He lit a match to prep the stove for use. Instead of igniting the gas to begin heating the stove, the match sparked a flame that raced up the pipe that connected the gas tank to the stove. Three employees—John Pardee, Aaron Cade, and John Piersoll—testified later that the cook yelled, “Fire!,” and all four men tried to douse the flames with water and wet oyster bags. But within seconds, the heat was so intense that they fled the building.

Visitors at the Centennial Exhibition saw smoke rising from the park’s entrance. Hundreds rushed toward the gates and saw flames leaping from the buildings on Elm Avenue just across the street. The first fire alarm went out from the Globe Hotel at 4:20 p.m. Philadelphia fire crews had dazzled spectators with their speed of deployment just one day earlier, but now it took twenty minutes for the first team to arrive at the blaze. It took another twenty minutes for the first stream of water to hit the fire, and that effort came from a group of policemen who attached a hose to a fireplug on a neighboring street.

The firemen quickly discovered that their fireplugs had fallen into disrepair. The plugs were clogged with sand and debris, and the firemen spent considerable time tearing them apart and cleaning them out. Meanwhile, a second alarm sounded from the United States Hotel down the block. Legions of people crowded Elm Avenue to gawk at the blaze and they made the situation worse for firefighters. Police arrived to control the crowds as the flames grew hot enough to scorch the fences around the Exhibition grounds. Behind the fences, the Main Building and Machinery Hall loomed above the flames. Two fire engines stationed themselves along the perimeter of the fairgrounds to battle the fire if it encroached on the exposition.

Nearly every structure on Tischner’s Avenue, a temporary street that connected two of the main arteries into the fairgrounds, was burned to the ground. The inferno ravaged buildings on Elm Avenue and did extensive damage to structures on nearby Columbia Avenue before firefighters finally gained the upper hand. Ultimately, the exposition remained unharmed, but organizers received the scare of a lifetime when they were in sight of the finish line.

Chris Wimmer is the creator, host, and lead writer of “Legends of the Old West,” a long-form, narrative podcast that tells true stories of the American West. He has a master’s degree in journalism from the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism at Arizona State University and has won numerous local, state, and national awards for his writing. The Summer of 1876 is his first book.