by Tom Clavin

Tensions were high in 1890 between white people and the indigenous people in the United States. Tom Clavin shares with The History Reader what sparked the Wounded Knee massacre that resulted in the death of most of the Lakota warriors, women, and children at the Pine Ridge Reservation.

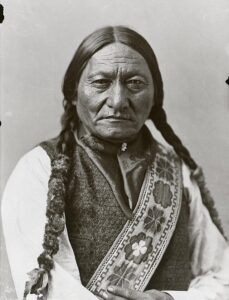

As the 7th Cavalry had done in November 1868 in the Washita River Valley and in June 1876 in the Bighorn River Valley, the troopers stealthily approached the Indian encampment on the Pine Ridge Reservation. This time, though, in December 1890, two weeks after the death of Sitting Bull, at Wounded Knee there would be a battle that would punctuate the end the Great Sioux War and with it the last resistance of indigenous people in the United States.

And finally, 14 years later, there would be vengeance for the bloody Little Bighorn defeat.

The ongoing promotion of the Ghost Dance coupled with the murder of Sitting Bull had raised tensions between the wasichus–white people–and the remaining Lakota and Cheyenne people. Even a small spark could touch off a fire.

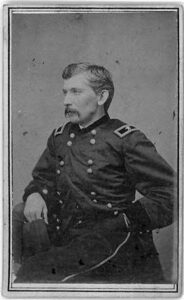

It began on December 28. Spotted Elk and 350 of his hungry and freezing followers were making the slow trip to the Pine Ridge Reservation. Southwest of Porcupine Butte, they were met by a 7th Cavalry detachment under Major Samuel Whitside. John Shangreau, a scout and interpreter who was half Lakota, advised Whitside not to disarm the Lakota immediately, as it would lead to violence. The commanding officer concurred and his troopers escorted the Lakota column about five miles westward to Wounded Knee Creek where they told them to make camp.

Later that evening, Colonel James W. Forsyth and the remainder of the 7th Calvary arrived, bringing the number of troopers at Wounded Knee to 500. The 350 followers of Spotted Elk consisted of 120 men and 230 women and children. Even though they showed no sign of agitation on that very cold night, troopers surrounded the encampment and set up four rapid-fire mountain guns.

At daybreak, Colonel Forsyth ordered the surrender of weapons and the immediate removal of the Lakota from the “zone of military operations” to awaiting trains. A search of the camp confiscated 38 rifles, and more rifles were taken as the soldiers searched the Lakota. None of the old men were found to be armed. A medicine man named Yellow Bird allegedly harangued the young men who were becoming irritated by the search, and the tension spread to the soldiers.

Specific details of what triggered the massacre are still being debated. According to some accounts, Yellow Bird began to perform the Ghost Dance, reminding the Lakota that their “ghost shirts” were bulletproof. As tensions mounted, Black Coyote refused to give up his rifle. He was not being obstinate–in addition to not speaking English, he was deaf and thus he was unable to hear or understand the order.

A fellow Miniconjou interceded, informing a soldier that Black Coyote was deaf. The Bluecoat persisted in trying to take the rifle, and he was soon assisted by two soldiers who seized Black Coyote from behind. During the ensuing struggle, his rifle discharged. That was all it took: Five young Lakota men with concealed weapons threw aside their blankets and fired their rifles at Troop K of the regiment, who began to return fire. Within seconds, the firing became indiscriminate.

At first, all firing was at close range. Reportedly, half the Lakota men were killed or wounded before they had a chance to get off any shots. But some of the Lakota grabbed rifles from the piles of confiscated weapons and opened fire on the soldiers. With no cover, and with many of the Lakota unarmed, this lasted a few minutes at most.

While the Lakota warriors and soldiers were shooting at close range, other soldiers used the mountain guns against the rest of the camp full of women and children. It is believed that many of the soldiers were victims of friendly fire from these guns. The terrified Lakota women and children who were not wounded fled the camp, seeking shelter in a nearby ravine. At that point, Forsyth and his senior officers lost all control of their men.

Some of the soldiers fanned out and finished off the wounded. Others leaped onto their horses and pursued the Sioux and Miniconjou women, children, and older men for a mile or more across the frozen prairie, which offered no natural shelters. In less than an hour, at least 150 Indians had been killed and 50 wounded. Other estimates indicate nearly 300 of the original 350 having been killed or wounded.

A blizzard blew in, preventing an immediate search following the massacre. Reports indicate that the soldiers loaded 51 survivors–four men and 47 women and children–onto wagons and took them to the Pine Ridge Reservation. Army casualties were reported to be 25 dead. Among the Miniconjou dead was Black Coyote.

Three days later, when the blizzard finally subsided, the military hired civilians to bury the dead Indians. The burial party found all the deceased to be frozen solid. They were gathered up–sometimes, limbs had to be broken–and placed in a mass grave on a hill overlooking the encampment. It was reported that four infants were found alive, wrapped in their deceased mothers’ shawls.

General Nelson Miles denounced Forsyth and relieved him of command. An exhaustive Army Court of Inquiry convened by Miles criticized Forsyth for his tactics but otherwise exonerated him of responsibility. The Secretary of War, Redfield Procter, reinstated Forsyth to command of the 7th Cavalry. He resumed a long career in the U.S. Army, retiring as a major general.

Incredibly, and no doubt to put a shiny gloss on a cold-blooded massacre, 19 troopers were awarded Medals of Honor for their actions at Wounded Knee. Some of the citations on the medals bestowed state that the troopers went in pursuit of Indians who were trying to escape or hide. Another citation was for “conspicuous bravery in rounding up and bringing to the skirmish line a stampeded pack mule.” Another medal was given in part for extending an enlistment.

Several efforts over the years–the most recent being the Remove the Stain Act introduced in Congress in May 2025 –have failed to have any of the Medals of Honor rescinded.

Originally posted on Tom Clavin’s The Overlook.

TOM CLAVIN is a #1 New York Times bestselling author and has worked as a newspaper editor, magazine writer, TV and radio commentator, and a reporter for The New York Times. He has received awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, and National Newspaper Association. His books include the bestselling Frontier Lawmen trilogy—Wild Bill, Dodge City, and Tombstone—and Blood and Treasure, The Last Hill, and Throne of Grace with Bob Drury. He lives in Sag Harbor, NY.