by Michael Cannell

Seymour Berkson may have been the only New Yorker to recoil at the sight of the psychiatric profile published on the front page of The New York Times on Christmas Day, 1956.

Any New Yorker who read newspapers knew that the police were scouring the city for a serial bomber who identified himself only as “F.P.” He had planted thirty-two homemade explosives in the city’s most crowded public spaces, injuring fifteen. F.P. had yet to kill, but it was only a matter of time. He was doling out more powerful bombs and shrewdly depositing them where dense crowds congregated—theaters, terminals, subway stations—a strategy that present grave dangers during the holiday season ahead. “Seldom in the history of New York,” wrote the Associated Press, “has a case proved such a torment to police.”

For more than a century the vaunted NYPD had relied muscle and shoe leather. But the reliable strong-arm methods proved useless in the face of a schizophrenic serial bomber. With the manhunt reaching critical urgency, the police took the unprecedented step of asking a psychiatrist, Dr. James Brussel, what the forensic evidence revealed about the bomber’s troubled inner life. What strange sort of person was he, and what wounding life experience led to his murderous avocation? In other words, they asked the psychiatrist to invent a new criminal science by peering into the mind of the bomber. The term profiling would not be coined for another two decades.

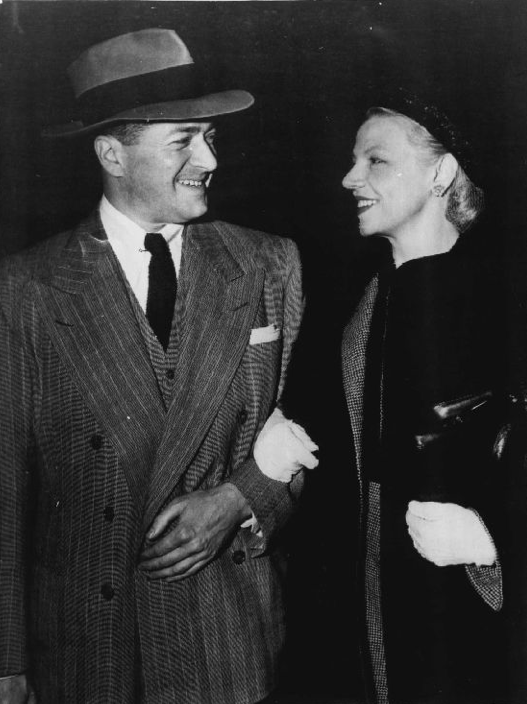

The New York Times broke the news of Dr. Brussel’s character analysis on Christmas morning. The psychiatrist had predicted that F.P. was Slavic, middle-aged and of medium build. He most likely resided with an older female relative in Connecticut, and he had a history of workplace disputes. The Times lay across the kitchen table of Seymour Berkson’s Fifth Avenue apartment like an unwanted holiday gift.

A publisher fighting for his newsroom’s survival could ask for no greater gift than a serial bomber such as F .P. The coverage sold newspapers, and it kept going and going. The Journal-American had followed the bomber story with glee and gusto. But now the Journal-American was in danger of falling behind. The bomber had twice written letters to the Herald Tribune. Now, on Christmas morning, Seymour Berkson woke to find The New York Times story about the psychiatrist, Dr. Brussel, and the portrait of the bomber’s inner life that he had drafted for the police. The Journal-American had catching up to do.

.P. The coverage sold newspapers, and it kept going and going. The Journal-American had followed the bomber story with glee and gusto. But now the Journal-American was in danger of falling behind. The bomber had twice written letters to the Herald Tribune. Now, on Christmas morning, Seymour Berkson woke to find The New York Times story about the psychiatrist, Dr. Brussel, and the portrait of the bomber’s inner life that he had drafted for the police. The Journal-American had catching up to do.

In newsroom parlance, the bomber story had legs. Gazing out over the winter-dead branches of Central Park, an idea came to Seymour Berkson: maybe the Journal-American could contact F.P. by publishing an open letter, possibly cajole him into revealing the exact nature of his grievance. Better yet, maybe the paper could play the role of negotiator, luring the bomber out of the shadows with the promise of legal and medical help.

Seymour Berkson was warned that that his plan could backfire. If F.P. interpreted the open letter as a trap, he might ratchet up his campaign, in which case the police—or worse, the readers—would blame the Journal-American. Still, the potential upside outweighed the risks. A letter to the mystery bomber, with the electrifying possibility of a correspondence, would set the Journal-American apart, but they faced a tricky piece of writing. The letter had to sound a sympathetic note, but not so consoling as to arouse F.P.’s suspicion. The letter, accompanied by an account of the “All-Out Search for Mad Bomber,” ran big and bold across all eight front-page columns:

AN OPEN LETTER

TO THE MAD BOMBER

(Prepared in Co-operation with the Police Dept.)

Give yourself up.

For your own welfare and for that of the community, the time has come for you to reveal your identity.

The N.Y. Journal-American guarantees that you will be protected from any illegal action and that you will get a fair trial.

This newspaper is also willing to help you in two other ways.

It will publish all the essential parts of your story as you may choose to make it public.

It will give you the full chance to air whatever grievances you may have as the motive of your acts.

We urge you to accept this offer now not only for your own sake but for the sake of the community.

Time is running out on your prospects of remaining unapprehended.

On the wall of Seymour Berkson’s newsroom office hung a taxidermic sailfish caught on an Acapulco vacation. “Keep your eyes open and your mouth shut,” he liked to tell reporters. “That sailfish did neither.” Seymour Berkson regarded the open letter to F.P. as another kind of fishing expedition: it was a lure cast into the deep, mysterious waters of New York. Over the following days the newsroom waited for the bomber to take the bait. Clerks checked every envelope and package for F.P.’s blocky handwriting. Every jangling phone brought a clutch of anticipation.

MICHAEL CANNELL is the author of The Limit: Life and Death on the 1961 Grand Prix Circuit and I.M. Pei: Mandarin of Modernism. He was editor of the New York Times House & Home section for seven years and has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, Sports Illustrated, and many other publications. He lives in New York City.