By Alex Von Tunzelmann

On 22 November 1963, CIA Special Affairs Section head Desmond FitzGerald was in Paris. The man he was to meet was Rolando Cubela. Cubela had been a member of the Cuban Revolutionary Directorate during the late 1950s, and fought alongside Che Guevara at the battle of Santa Clara. He seemed to be in and out of favor with the Cuban government, and had been trying to defect since the Bay of Pigs invasion. Two and a half months earlier, he had presented himself to the CIA in Brazil as a potential assassin. FitzGerald was meeting him to set up the murder of Fidel Castro.

Cubela had stated that he wanted to meet Bobby Kennedy personally, indicating that he knew enough about Operation Mongoose to know who was in charge. The request had been denied, but FitzGerald— a friend of both Kennedy brothers— told Cubela he spoke for Bobby.

FitzGerald gave Cubela a fountain pen fitted with a concealed needle, and filled not with ink but with Blackleaf 40. The toxin was designed to kill. Cubela was to return to Cuba, where the CIA had planned to deliver him a rifle as well. Before 22 November, though, counterintelligence agents within the CIA had doubts about Cubela. After his first contact two months earlier, a reporter for the Associated Press had spoken to Fidel Castro privately at a party in Havana. Fidel had told him he knew the American government was planning to kill him. “United States leaders should think that if they assist in terrorist plans to eliminate Cuban leaders, they themselves will not be safe,” he said.

Perhaps the timing of Fidel’s remark was a coincidence. Perhaps Cubela was a double agent, and had told Fidel what was afoot. There was enough circumstantial evidence for the counterintelligence agent on FitzGerald’s team to warn that Cubela was “insecure” before the meeting. FitzGerald went ahead with the rendezvous anyway, but, when he left Cubela, he was greeted with a piece of shocking news. His friend and president, John F. Kennedy, had just been shot.

***

It had been a beautiful Texas morning. A glamorous couple emerged from their plane at Love Field. They drove through Dallas surrounded by a motorcade, the chrome on their limousine gleaming in the midday sun. Two flags fluttered from the hood. The president and the first lady waved and smiled at the crowds as the limousine turned into Dealey Plaza and down Elm Street. Suddenly, the president seemed to grip his throat and lean forward. His wife turned to him. Then came the awful shot, that horrific, unforgettable moment. A flash of red. The president’s head recoiled. Blood splashed over Jackie Kennedy’s neat white gloves and pink wool suit.

Bobby Kennedy had just finished eating a tuna sandwich by the pool in the backyard of his home, Hickory Hill, in McLean, Virginia. His wife, Ethel, answered a call put through to the poolside telephone. It was J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI. Jack Kennedy had been shot, but no one knew how serious it was. Ethel took her husband in her arms, and the two headed for the house, where Bobby made plans to fly to Dallas. He wondered, vaguely, who might have done it. “There’s been so much hate,” he said. Then came the second call. Jack was dead.

At the moment the news broke, Fidel Castro was speaking to Jean Daniel of L’Express, who had conveyed to him Kennedy’s message of possible reconciliation. During the meeting, the telephone rang with news of the president’s shooting. “This is bad news,” Fidel said to Daniel. “This is bad news.”

By contrast, François Duvalier was not sorry at all. He claimed to be the murderer. According to some colorful sources, on the morning of 22 November Papa Doc had stabbed his John F. Kennedy “voodoo doll” 2,222 times. That is probably not true, for voodoo dolls are not generally associated with Haitian Vodou; but Duvalier had put a death curse on Kennedy in May 1963, and he did consider twenty-two to be his lucky number. When the curse seemed to have worked that day, he was not at all surprised. He called for champagne, and sent the Tontons Macoutes out to organize public celebrations. They skipped through the streets, shouting, “Papa Doc may govern in peace, for his biggest enemy is gone!” There was a spontaneous carnival. The octogenarian Haitian intellectual Dantès Bellegarde wrote a commemorative pamphlet mourning Kennedy, and earned himself a beating by the chief of the Tontons Macoutes.

Never have so many conspiracy theories sprung up around the death of one man than sprang up around the death of John F. Kennedy. There was no shortage of suspects. It was the communists. It was the Cuban exiles. It was the Secret Service. It was the FBI. It was the CIA. It was a rogue CIA conspiracy, led by David Atlee Phillips, Bill Harvey, and the JM/WAVE station in Miami. It was the CIA’s counterintelligence chief, James Jesus Angleton. It was the bankers. It was the Israelis. It was the military-industrial complex. It was three suspiciously well-groomed tramps loitering by the grassy knoll. It was Kennedy’s own bodyguard, firing at the assassin and hitting the president by mistake. It was Nikita Khrushchev. It was Sam Giancana. It was Jimmy Hoffa. It was Meyer Lansky. It was Santo Trafficante. It was the New Orleans mafioso Carlos Marcello. It was the right-wing oil magnate H. L. Hunt. It was François Duvalier and his sorcerers. Lee Harvey Oswald was a Soviet agent. He was a Cuban agent. He was an impostor. He was a communist stooge. He was a Mafia stooge. Jack Ruby was also a Mafia stooge. A KGB agent in New York said it was the KGB. The KGB said it was E. Howard Hunt. E. Howard Hunt said it was Lyndon Johnson. Lyndon Johnson said it was Fidel Castro. According to Bobby Kennedy, who had heard it from Pierre Salinger, Johnson really thought it was God: “He said that when he was brought up, he knew a young boy who wasn’t very good, and the young boy ran into a tree on a bike, or something, and became crosseyed. And he thought that that was God’s way of showing him and others that you shouldn’t be bad, and this was retribution for being bad,” Bobby remembered. “And then he said, in that context, that he thought because of President Kennedy’s involvement in the assassination of Trujillo and [South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh] Diem, that this was retribution— that his assassination in Dallas was retribution for that.”

On 29 November, Johnson told a group of his political friends that the assassination “has some foreign complications, CIA and other things. . . . We can’t just [have] House and Senate and FBI people going around testifying [that] Khrushchev killed Kennedy or Castro killed him— we’ve got to have the facts.” That same day, he telephoned the likes of Allen Dulles and the chief justice, Earl Warren, asking them to serve on an investigative commission. One of those he asked was Richard Russell, a Democratic senator from Georgia and an old friend of Dulles.

Russell said that he did not believe the Russians were involved, but “wouldn’t be surprised if Castro—”

Johnson interrupted: “Okay, okay, that’s what we want to know.”

That commission, which became known as the Warren Commission, would famously create more of a mystery than it solved. Concerned, still, with plausible deniability, and with the CIA’s reputation, Allen Dulles made sure that the commission operated without any knowledge about the intricacy and extent of the Kennedy brothers’ ties to the Mafia or the Cubans training in Miami, and without any knowledge of the secret war the Kennedys had been waging against Fidel Castro. The Warren Commission concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald was a lone gunman, acting alone.

Since then, every detail of Jack Kennedy’s death and the circumstances around it has been questioned, and every frame of film scrutinized. The attention of countless experts, professional and amateur, has been focused obsessively upon the logistics, forensics, and physics of those few seconds in Dealey Plaza, and the knots and hoops of the massive web of connections surrounding it. Instead of a consensus, this investigation has delivered endless branching complexities. But the fact that there was, undoubtedly, a very large number of people and interests with a reason to seek Kennedy’s death— and the fact that some of them may have seriously considered having him killed— does not prove that they were involved in the act itself. The fact that some of those people and interests arguably benefited from Kennedy’s death does not prove that they were involved, either. The existence of irregularities in the initial investigation or Warren Commission report does not prove that everything in it is wrong—not even, necessarily, its conclusions. Human error and the inevitable confusion in people’s perceptions and memories of traumatic events often give rise to inconsistencies. And the fact that many people and bodies, including the House Special Committee on Assassinations, which reviewed and critiqued the Warren Commission, believe there to have been a conspiracy does not prove that there was a conspiracy. The plural of opinion—even of educated and informed opinion—is not evidence.

“I’ll tell you something that will rock you,” Lyndon Johnson confided to the journalist Howard K. Smith in 1966. “Kennedy tried to get Castro—but Castro got Kennedy first.” If the Kennedy assassination were an event in a novel, it would be an irresistible twist: the Kennedy brothers spend tens of millions of dollars on dozens of schemes to kill Castro, but then, with one perfectly aimed, knockout blow, David slays Goliath. But there is no direct evidence that Fidel Castro, or any part of the Cuban government or secret ser vices, was involved in Kennedy’s assassination. There is an enormous patchwork of hints and possible coincidences, but they lend justas much, if not more, credibility to the theory that anti- Castro Cuban exiles, possibly in league with the Mafia, did it, as to the theory that pro-Castro Cubans did it.

Many years later, Raymond Garthoff , a special assistant in the State Department for Soviet bloc affairs, discussed with Fidel Castro the apparent inconsistency of Jean Daniel arriving with Kennedy’s positive message to Fidel at the same time a poison pen was being given to Rolando Cubela. “There were contradictory strands in U.S. policy toward Cuba in 1963,” Garthoff admitted, “but also, perhaps, it was one of those cases where the right hand did not know what the far-right hand was doing.” Fidel was sanguine about it: “Someone was giving someone a pen with a poison dart to kill me, exactly on the same day and at the same time that Jean Daniel was talking to me about this message, this communication from President Kennedy,” he mused. “So you see how many strange things— paradoxes—have taken place on this Earth.”

The fact that Dulles and the CIA concealed from the Warren Commission the CIA’s activities against Fidel Castro was a grave omission. “Because we did not have those links,” explained the Warren Commission attorney Burt Griffin, “there was nothing to tie the underworld in with Cuba and thus nothing to tie them in with Oswald, nothing to tie them in with the assassination of the President.” It is the cover-up itself that has fueled the conspiracy theories. But the fact that the CIA covered up its own plots against Castro does not prove, or even substantiate, the theory that the CIA killed Kennedy, that Castro killed Kennedy, that the anti-Castro Cubans killed Kennedy, or that the Mafia killed Kennedy. All it proves is that the CIA was a shady organization determined to evade public accountability, and that is no surprise to anyone.

The CIA’s files on Kennedy’s assassination are due for declassification in 2029. Even after they are opened, the case may never be closed. The mystery has endured for so long, and has become so elaborate, that whatever emerges is unlikely to be believed by large numbers of people. The supporters of the Castro theory will not believe it was the Mafia; the supporters of the Mafia theory will not believe it was Castro; the supporters of the CIA theory will forever believe it was the CIA, because any evidence that emerges for any other theory might just be further evidence planted by the CIA to cover its own role; and none will believe that Lee Harvey Oswald was a lone gunman, acting alone.

In the early evening of 22 November, Air Force One landed in Washington. It was carrying Jack Kennedy’s body, the distraught Jackie, still in her bloodstained pink suit, and the new president of the United States of America, Lyndon B. Johnson, who had taken the oath of office on board with Kennedy’s shell-shocked widow at his side.

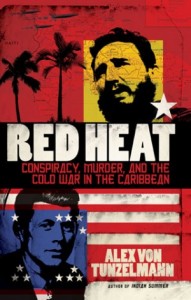

Excerpted from Red Heat: Conspiracy, Murder, and the Cold War in the Caribbeanby Alex von Tunzelmann.

Copyright © 2011 by Alex von Tunzelmann.

Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the publisher.

ALEX VON TUNZELMANN is the author of Red Heat: Conspiracy, Murder, and the Cold War in the Caribbean and Indian Summer: The Secret History of the End of an Empire.