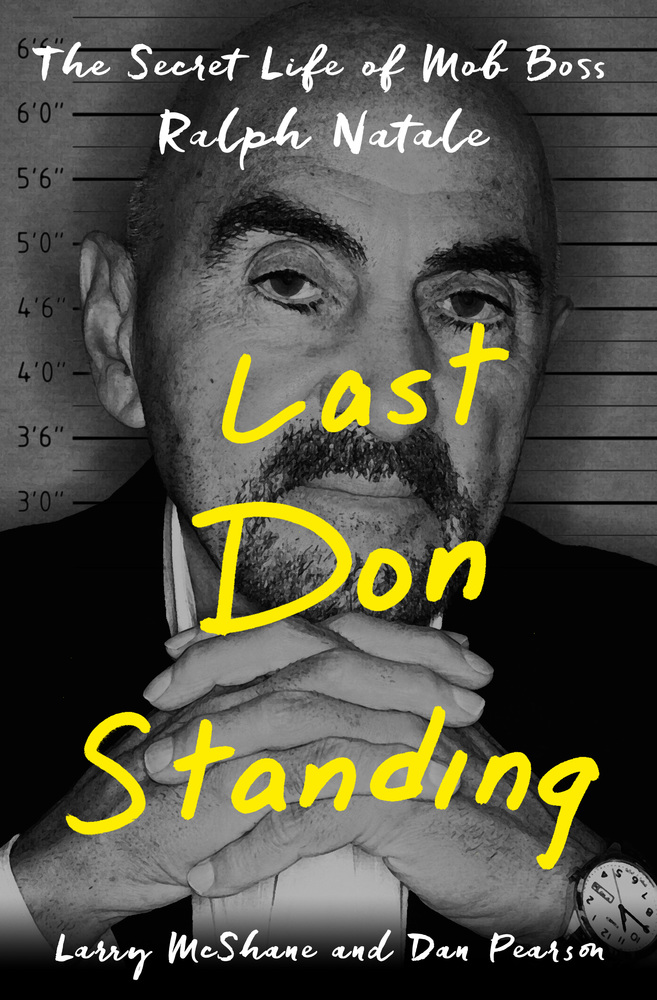

by Dan Pearson and Larry McShane

When the call came, Ralph Natale reflected on exactly how long it had been since he’d laid eyes on Jimmy Hoffa. Their final meeting was tinged with melancholy rather than the bravura of their initial get-together—a sad coda to a close friendship. Hoffa was reaching out after a run of hard luck and hard times.

For more than four years, Jimmy Hoffa ran the powerful International Brotherhood of Teamsters from behind bars in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, with his handpicked general vice president, Frank Fitzsimmons, representing the boss on the outside. Hoffa, after a brutal and bruising legal war with the government, went to jail in 1967 after convictions for conspiracy and misusing the union’s pension funds.

Jimmy Hoffa cut a 1971 deal for his freedom, but it came with a price: the veteran labor organizer agreed to resign his post atop the Teamsters and never again serve as a union official. Hoffa was promised, before heading to prison, that his successor Fitzsimmons could resign and surrender the union once Hoffa was back on the streets.

But things had changed in his absence, and Fitzsimmons— with the backing of some prominent mob leaders—wasn’t going anywhere. Hoffa was undeterred and began angling to regain control of his union and its top spot.

“Fitzsimmons went to see (Genovese family boss) Fat Tony Salerno, who told him, ‘Don’t worry about him. Jimmy Hoffa will be talked to, and this will be straightened out,’ ” said Natale. “Of course, nobody kept their word.”

The possibility of Jimmy Hoffa’s running for the union’s top spot in 1976 soon emerged as his likeliest road to Teamsters redemption. Hoffa, behind the scenes, contacted some of his old friends to see if such a move was plausible—a clandestine tour to see who was willing to back his play.

Natale was hardly surprised by this bold move: “They couldn’t change Jimmy. They could tell him what to do, but they couldn’t change his manhood. He was a great union leader. And he had some balls. I heard he was gonna do this or that.”

The final meeting of Natale and Hoffa took place in the Rickshaw Inn, a restaurant with a gold-flecked roof and a huge half-a-horseshoe-shaped bar opposite the Cherry Hill racetrack. A few days earlier, Natale was at the offices of Local 170 when the phone rang. It was John Greeley, head of the South Jersey Local 676 and one of area’s most influential labor leaders.

“Calls me out of the clear blue sky,” said Natale. “John says, ‘That guy’s in town. He wants to see you.’ I knew what he means. And I said, ‘Oh, yeah? Okay.’ ”

Natale, unsure what to expect, arrived for the 1:00 p.m. get-together with two killers from his crew, Turchi and Marrone—the latter a truly terrifying figure who once attended a wedding reception with a hatchet tucked in the small of his back. “Just in case,” he explained.

Natale, unsure what to expect, arrived for the 1:00 p.m. get-together with two killers from his crew, Turchi and Marrone—the latter a truly terrifying figure who once attended a wedding reception with a hatchet tucked in the small of his back. “Just in case,” he explained.

Natale figured he was better safe than eternally sorry. “I never knew when people called me what’s gonna happen,” he said. “ ’Cause in those days, everything was comme ci, comme ça—I might have some crazy people wanna take a shot at me. I’m gonna go down blazing. I ain’t gonna walk into something.

“In our life, you’re only killed by your friends—or people pretending to be your friends. That’s our life.”

His fears were unfounded. And unlike their previous meeting in Detroit, when the union world belonged to an all-powerful Jimmy Hoffa and the future appeared limitless, a feeling of impending doom lingered this time.

“Anyway, I went and it was just terrible,” Natale recounted. “It’s about one in the afternoon, it’s dark in the lounge. At the far end of the horseshoe, there’s Jimmy and John Greeley. Jimmy comes up and shakes my hand. We hugged like men.”

The old friends exchanged pleasantries, and before long Greeley excused himself, leaving Hoffa and Natale to discuss the business at hand: the reincarnation of James Riddle Hoffa.

Hoffa spoke first: “I heard you’ve been busy.” Natale smiled, and then Hoffa got down to business: “I guess you know why I’m here.” “I said, ‘I hear a lot of things through the grapevine.’ I’d heard different people telling me about it, people that meant something. “He said, ‘Ralph, I’m gonna need some help in Jersey. John Greeley already said he was with me, if I run.’ And John would. He was that kind of man. Jimmy said, ‘The next convention, I’m gonna take the thing back by acclaim and I need your help. Would you help me like you always helped me?’”

Natale looked directly at the powerful union leader, a look that expressed both his admiration and the dilemma he was now facing. Finally he spoke: “Jimmy, you know who was I with since I was a boy—before I was a boy. When I was in my mother’s womb, my father was with them, and I’m with them. So let me tell you one thing first: ‘A man cannot serve two kings.’ ”

Hoffa offered a wry grin before responding, “Ralphy, I knew you were going to say that.” Unmentioned was the name of Angelo Bruno, who would make the ultimate decision on Philly’s support of Hoffa.

Natale then offered a biblical reference to his boss: “Listen, if he—like Pontius Pilate—washes his hands of it, says he’s not involved in all this stuff against you, I’m gonna help you in a minute. I know Fitzsimmons broke his word to you, I was told by a hundred people.”

Hoffa was expecting the answer, and he knew Ralph’s response meant support from the Philadelphia faction was a pipe dream. He looked right back at Natale: “I knew you would say that. And I respect that. But I wish you said, ‘If he looks the other way, I’ll help you and do whatever you need.’ ”

The mood turned darker than the dim bar lights as the two old friends sat in silence, their brief conversation signaling with a black future for Hoffa. The implications were not lost on Natale, either.

“He already knew the answer, but he had to ask me,” Natale said. “When he said he understood, I felt like I was at his funeral. I could smell the dirt of the grave on him. That’s how I felt, right then and there in that room. I hadn’t felt, up to that time, so bad in all my life, until I looked at him. I’m pretty coldhearted about these things, but my heart went out to him.”

“He was dead. He was a dead man talking to me. I said, ‘Jim, are you sure?’ “And he said, ‘I have to do this. It’s the only thing I have.’ I looked at this man, who could get killed for doing what he thought was right. And he was right—he was ten times the man that Fitzsimmons was.”

Natale awoke the next morning and drove directly to Bruno’s house to speak with the boss about the Hoffa situation. Bruno’s wife, Sue, answered his knock, and invited Ralph in for a cup of coffee and a few minutes of her husband’s time. When Bruno appeared, Natale recounted his meeting at the Rickshaw.

The boss’s response was hard and fast: “You know I love Jimmy. But there’s no reason for him to do this. It’s wrong. Even if he calls you and says it’s an emergency, stay away. That man up in Jersey [Tony Provenzano] is going to take care of this. Please, don’t forget what I said.”

Natale, as usual, kept his mouth shut and remembered every word. The boss’s edict was final, a Philadelphia epitaph for Jimmy Hoffa’s reign. “And I thought, ‘Oh my God.’ It wasn’t long after that he disappeared,” Natale recalled.

He never saw or spoke to Jimmy Hoffa again. The mighty labor boss disappeared on July 30, 1975. “I couldn’t get over it for weeks. I felt terrible—oh, I felt bad,” Natale recalled. “And for me—I seen a lot of things, I done a lot of things—it bothered me. I respected him so much as a man.”

In an odd quirk, law enforcement summoned Natale as they investigated Jimmy Hoffa’s death, asking about their afternoon at the Rickshaw. The mob killer was insulted at the insinuation that he was involved: “I said, ‘Don’t even ask that. I would never do that. You know my MO—not with friends.’ ”

LARRY MCSHANE is a 35-year veteran city reporter currently with the New York Daily News. The award-winning Seton Hall University graduate was a two-time AP New York State Staffer of the Year. He is the author of Cops Under Fire and Chin: The Life and Crimes of Mafia Boss Vincent Gigante.

DAN PEARSON is the executive producer of Discovery’s I Married a Mobster and has been an entertainment industry veteran for over twenty years.