by Heath Hardage Lee

On February 12, 1973, one hundred and sixteen men who, just six years earlier, had been high flying Navy and Air Force pilots, shuffled, limped, or were carried off a huge military transport plane at Clark Air Base in the Philippines. These American servicemen had endured years of brutal torture, kept shackled and starving in solitary confinement, in rat-infested, mosquito-laden prisons, the worst of which was The Hanoi Hilton.

Months later, the first Vietnam POWs to return home would learn that their rescuers were their wives, a group of women that included Jane Denton, Sybil Stockdale, Louise Mulligan, Andrea Rander, Phyllis Galanti, and Helene Knapp. These women, who formed The National League of Families, would never have called themselves “feminists,” but they had become the POW and MIAs most fervent advocates, going to extraordinary lengths to facilitate their husbands’ freedom—and to account for missing military men—by relentlessly lobbying government leaders, conducting a savvy media campaign, conducting covert meetings with antiwar activists, and most astonishingly, helping to code secret letters to their imprisoned husbands.

Keep reading for an excerpt from the true, untold story of these remarkable women: Heath Hardage Lee’s The League of Wives.

* * * * *

In the 1960s, Navy fighter pilots had a 23 percent likelihood of dying in an aircraft accident over a twenty-year career—not including combat deaths. In order to survive in this line of work, a man had to possess an enormous ego—one that rivaled those of heads of state or Hollywood film stars. Confidence, a steady hand, and the idea that you could never, ever be shot down were requirements for anyone in this dangerous business. If you thought for more than two seconds about what you were doing, you would most likely end up dead—and kill everyone else on the plane with you.

A 1975 study in Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine on “the outstanding jet pilot” found that many successful pilots were first- born children with a close relationship with their father, “reinforcing ‘positive male identification.’” Another finding from the same study noted that “21 of the first 23 astronauts who went on space flights were first born. The pilots were self-confident, showed a great desire for challenge and success and were non-introspective.” In author Tom Wolfe’s famous words, these men were made of “the right stuff.”

A 1975 study in Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine on “the outstanding jet pilot” found that many successful pilots were first- born children with a close relationship with their father, “reinforcing ‘positive male identification.’” Another finding from the same study noted that “21 of the first 23 astronauts who went on space flights were first born. The pilots were self-confident, showed a great desire for challenge and success and were non-introspective.” In author Tom Wolfe’s famous words, these men were made of “the right stuff.”

The right stuff extended beyond the professional into the personal; a pilot had to enjoy parties, since his time on earth might be short. He had to be able to hold his liquor (lots of it) at night, and then get up at the crack of dawn and climb into the cockpit before his morning coffee.

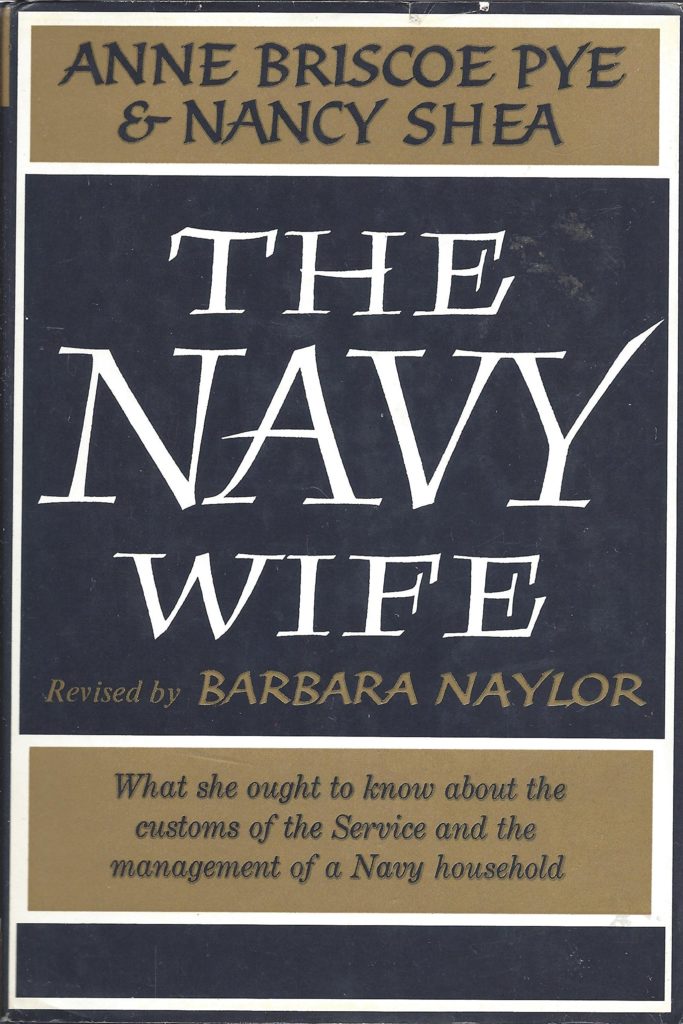

Finally, a pilot needed the right wife: attractive, kind, a model mother, and an excellent cook. Her job was to be sure he could do his job. The military cranked out training manuals for her that were every bit as rigorous as his. Each branch of the service put officers’ wives through their own kind of basic training, advising the young women who married into the military on everything from their wedding-night lingerie to “Conversational Taboos at Social Gatherings.” Women were judged on their abilities in the domestic sphere above all, and were given advice from senior wives, such as “The food you serve and the way you serve it are just as revealing as the kind of person you are as the house which is your background and the clothes you wear. It is fun to dream up new color combinations in both decorations and in foods.”

The Navy Wife was a government-approved guide to the rules of naval etiquette and hierarchy. A wife’s status mirrored her husband’s rank. Everything she did or said would reflect on him and could affect his career. More than one social faux pas in their byzantine world of calling cards, shrimp forks, and proper thank-you notes might result in a young officer getting “passed over” for a promotion. More serious offenses could even end in exile at some desolate military outpost. Most military wives realized that their “best interest (promotion, advancement, success in any form) was accomplished by playing within the rules.” In this way, the wives were empowered to play a significant role in their husbands’ careers, and thus in their own lives and those of their families.

The Navy Wife was a government-approved guide to the rules of naval etiquette and hierarchy. A wife’s status mirrored her husband’s rank. Everything she did or said would reflect on him and could affect his career. More than one social faux pas in their byzantine world of calling cards, shrimp forks, and proper thank-you notes might result in a young officer getting “passed over” for a promotion. More serious offenses could even end in exile at some desolate military outpost. Most military wives realized that their “best interest (promotion, advancement, success in any form) was accomplished by playing within the rules.” In this way, the wives were empowered to play a significant role in their husbands’ careers, and thus in their own lives and those of their families.

Customs from Victorian times still prevailed in the Navy and other service branches. The tradition of formal calls upon senior servicemen by junior officers and their wives was standard. Both the officer and his wife had their own calling cards, which had to be presented during “calling hours” at the home of the senior officer. Cards were typically left on a silver tray placed in the household just for this purpose. “A man leaves a card for each adult in the house . . . a woman never calls on a man, you leave cards only for the adult women of the household.”

Young Navy wives were cautioned, “Wives influence their husbands in many ways, and the excellence of a man’s performance of duty has a direct relationship to the happiness and stability of his home life.” Army wives were cautioned, in their own The Army Wife protocol manual, not to be “a stone around his neck.”

The Air Force Wife manual laid out perhaps the most potent psychological message to young military wives: without a tranquil home life, disaster was just around the corner. A pilot’s blood—and the blood of his colleagues—might just end up on his wife’s hands. “It is said that domestic troubles have killed more aviators than motor failures, high-tension wires and low ceilings, so as an Air Force wife your responsibility is great and your job is of big proportions if you live up to the finest traditions of this Service.”

These military messages of exacting protocol created a powerful bond among the pilots’ wives. While their husbands risked death in distant lands, their wives developed a code of support of their own that was reinforced in a positive manner by the military. These women were encouraged to cultivate “a kind of empathy unknown to civilian wives—an identification, a pride… in your husband’s role.” Until the Vietnam War, however, many of these wives would have no idea how critical this support for one another would become.

Heath Hardage Lee comes from a museum education and curatorial background, and she has worked at history museums across the country. She holds a B.A. in History with Honors from Davidson College, and an M.A. in French Language and Literature from the University of Virginia. Heath served as the 2017 Robert J. Dole Curatorial Fellow: her exhibition entitled The League of Wives: Vietnam POW MIA Advocates & Allies about Vietnam POW MIA wives premiered at the Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics in May of 2017 and is now travelling to museums throughout the U.S. Potomac Books, a division of the University of Nebraska Press, published Heath’s first book, Winnie Davis: Daughter of the Lost Cause, in 2014. Winnie won the 2015 Colonial Dames of America Annual Book Award as well as a 2015 Gold Medal for Nonfiction from the Independent Publisher Book Awards. Heath lives in Roanoke, Virginia, with her husband Chris and her two children, Anne Alston and James.