by Jack Kelly

Shakespeare, of course, wrote acclaimed plays about history. But sometimes history takes the pen from the playwright’s hand and fashions a scenario of such startling tension and originality that the story seems destined for the stage. One of these dramas took place in September 1780. It involved the plot by Benedict Arnold to betray the patriot cause and to help the British prevail in the Revolutionary War.

Arnold, an important hero of the American Revolution, decided to change sides in the summer of 1779. Why? Historians have scratched their heads over that question for generations. They have suggested everything from “he did it for the money” to “his wife made him.” The fact is, we don’t know. And maybe he didn’t really know himself.

But it happened. His plan was to wait until he was in a position to assure an enemy victory. The opportunity came when he was put in charge of the lower Hudson Valley, including the critical fort at West Point, which controlled access to the river. A successful British attack there could be decisive.

On Thursday night, September 21, 1780, Arnold met with the chief of British intelligence, Major John André, near Peekskill, New York, to finalize the deal. Arnold gave André a map of West Point’s defenses and instructions for capturing the fort. The traitor then returned to his headquarters on the riverbank opposite West Point. André, after some delay, began riding south along the eastern shore on Saturday morning, September 23.

The territory André had to cross included a stretch of Westchester County between the American and British lines. André was excited—he had pulled off the biggest intelligence coup of the war. He was also nervous—militiamen from both sides roamed this no man’s land. He rode as far as Sleepy Hollow, the wooded region that Washington Irving would depict as the haunt of the Headless Horseman.

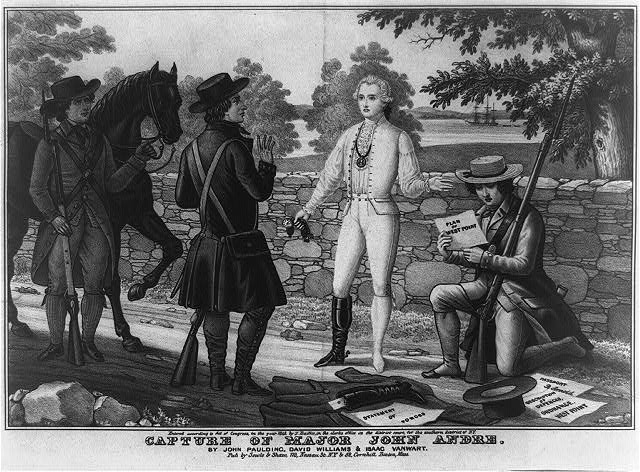

Suddenly, three armed militiamen emerged from the brush and ordered him to halt. André was disguised as a civilian and was carrying the vital plans in his boot. He didn’t know which side the men were on, only that they were aiming cocked muskets at his chest.

“I hope you are of our party,” he said.

One wary militiaman replied, “Which party is that?”

André had to guess. “The lower party,” he said, meaning the British, who controlled New York City.

“We’re Americans,” the other man told him. “Get down.”

The men searched André, found the suspicious papers, refused the generous bribes he offered, and took him to Lieutenant Colonel John Jameson, who was in charge of the region. Obedient to the chain of command, Jameson sent a courier off to inform his direct superior, Benedict Arnold, of the suspicious activity. On second thought, he decided to dispatch the incriminating documents directly to George Washington.

Maybe not even Shakespeare could have come up with the twist that followed. George Washington was just then returning from a meeting with French officers in Hartford Connecticut. Having stayed Sunday night in Fishkill, New York, he planned to eat breakfast the next morning with Arnold. Afterward, they would inspect West Point together before Washington returned to the Continental Army camp on the New York-New Jersey border.

On Monday morning, September 25, the two couriers were winding their separate ways toward Arnold’s headquarters. There the traitorous general and his wife awaited the commander-in-chief while their cook prepared a hearty breakfast. Arnold was on edge—confident that Andre had gotten through, he assumed the attack on West Point could begin at any time.

Which messenger would arrive first? Who would get the news? Was it too late to foil the plot? All would be answered in the climactic Act III that followed, a scene for the ages.

During the decades after the Revolution, playwrights did often depict this very drama on stage. Among the heroes were the three lowly militiamen, who were, for a while, quite famous. Their names were John Paulding, David Williams, and Isaac Van Wart. It was said that only Paulding could read.

Their virtue in refusing André’s bribes was celebrated. Congress declared that each man should receive a silver medal for his valor. These are considered the oldest military decorations in U.S. history. They were inscribed on the front with a single word: “Fidelity.”

* * *

Read the dramatic conclusion to the story in God Save Benedict Arnold: The True Story of America’s Most Hated Man (coming December 5, 2023).

Originally published on Jack Kelly’s Talking to America.

Jack Kelly is a journalist, novelist, and historian, whose books include Band of Giants, which received the DAR’s History Award Medal. He has contributed to national periodicals including The Wall Street Journal and is a New York Foundation for the Arts fellow. He has appeared on The History Channel and been interviewed on National Public Radio. He grew up in a town in the canal corridor adjacent to Palmyra, Joseph Smith’s home. He lives in New York’s Hudson Valley.