by Hugh Ryan

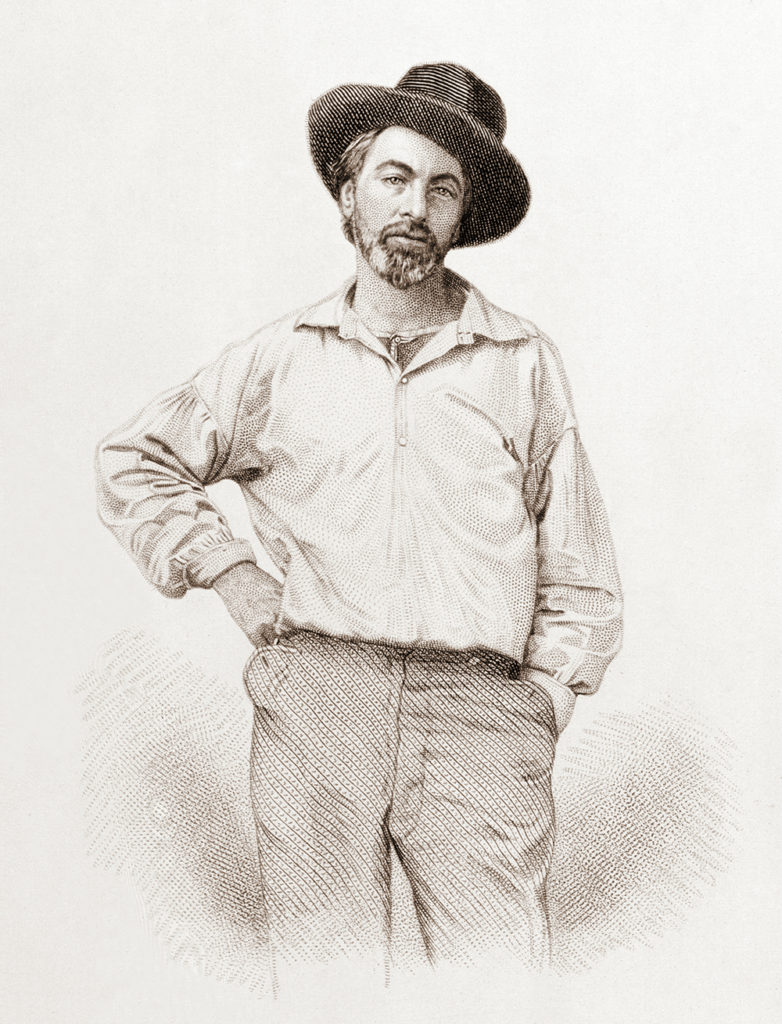

Hugh Ryan’s When Brooklyn Was Queer is a groundbreaking exploration of the LGBT history of Brooklyn, from the early days of Walt Whitman in the 1850s up through the queer women who worked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard during World War II, and beyond. No other book, movie, or exhibition has ever told this sweeping story. Not only has Brooklyn always lived in the shadow of queer Manhattan neighborhoods like Greenwich Village and Harlem, but there has also been a systematic erasure of its queer history—a great forgetting.

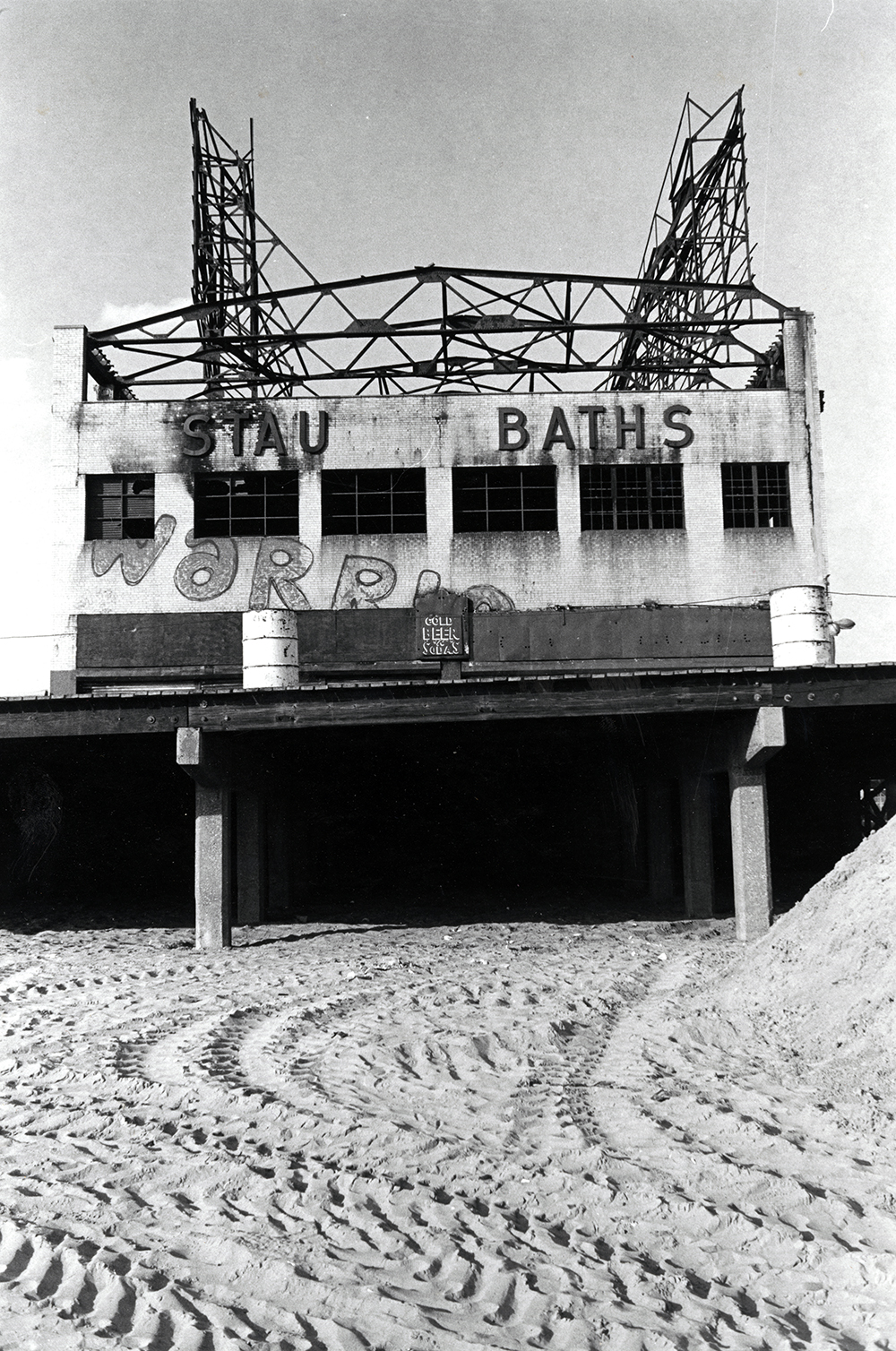

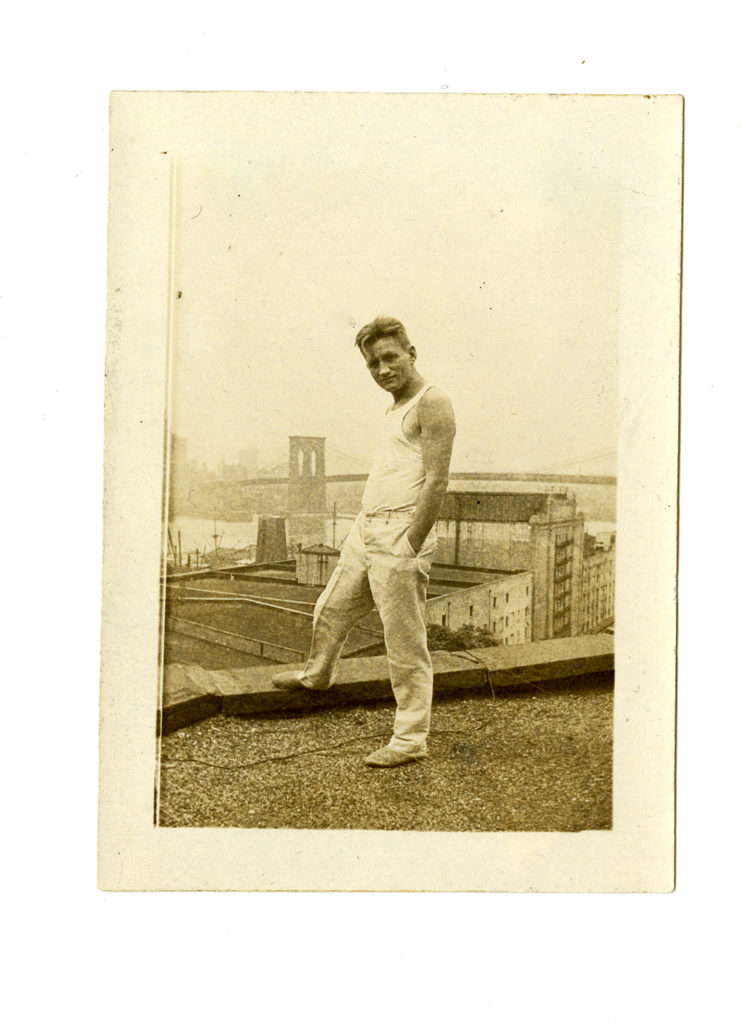

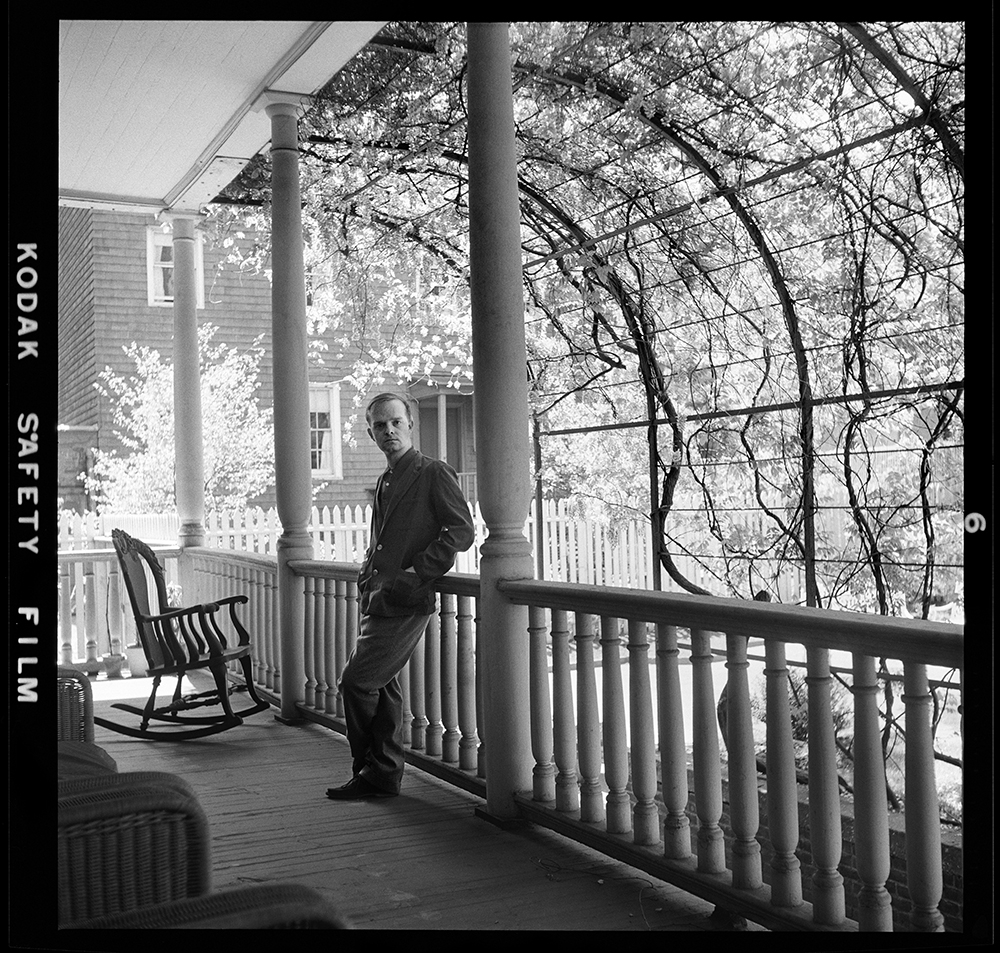

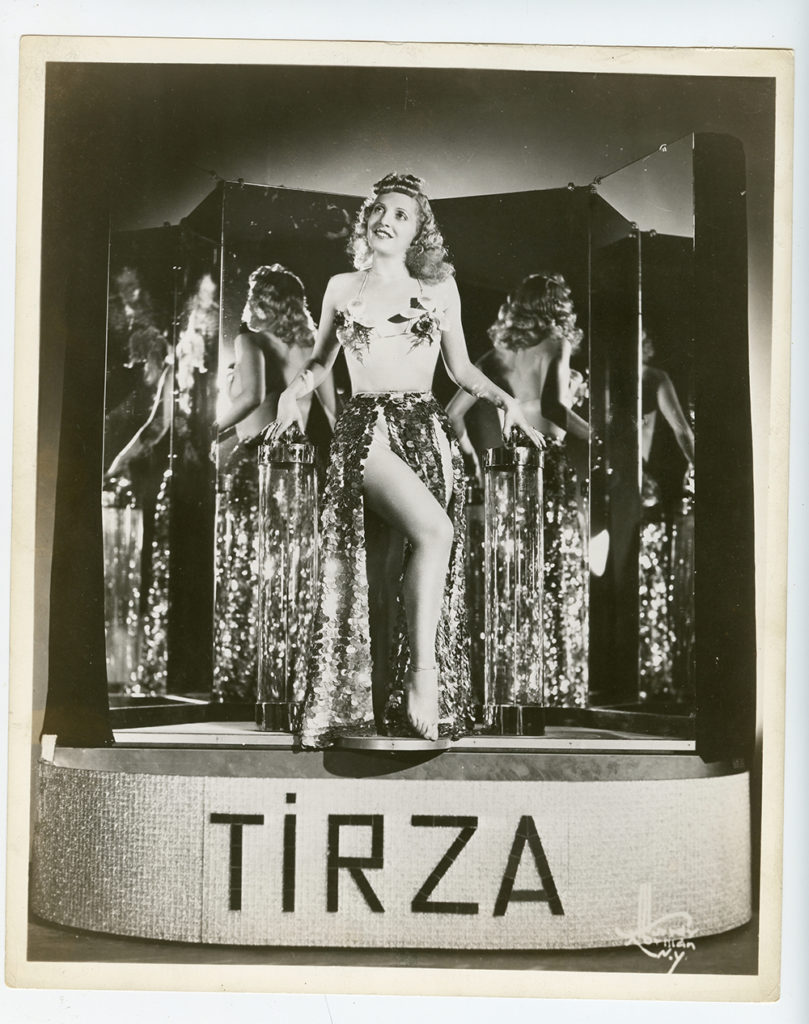

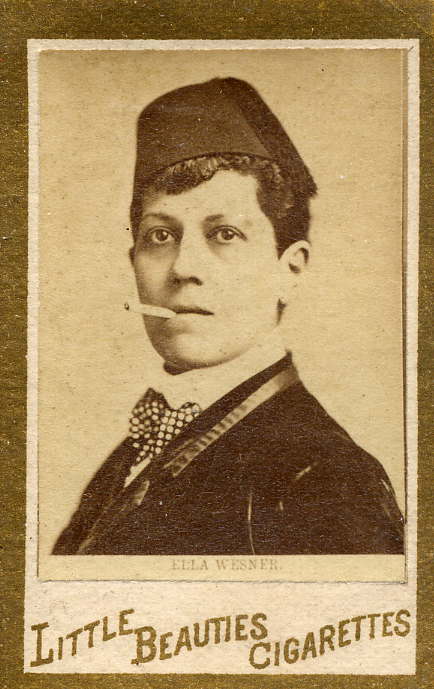

Ryan is here to unearth that history for the first time. In intimate, evocative, moving prose he discusses in new light the fundamental questions of what history is, who tells it, and how we can only make sense of ourselves through its retelling; and shows how the formation of the Brooklyn we know today is inextricably linked to the stories of the incredible people who created its diverse neighborhoods and cultures. Through them, When Brooklyn Was Queer brings Brooklyn’s queer past to life, and claims its place as a modern classic. Keep scrolling to explore a selection of photographs from the book.

Hugh Ryan is a writer and curator based in Brooklyn. He is the Founder of the Pop-Up Museum of Queer History, and sits on the Boards of QED: A Journal in LGBTQ Worldmaking, and the Museum of Transgender Hirstory and Art. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Tin House, Buzzfeed, the LA Review of Books, Out, and many other venues. He is the author of When Brooklyn Was Queer, and is the recipient of the 2016-2017 Martin Duberman Fellowship at the New York Public Library, a 2017 New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in Nonfiction Literature, and a 2018 residency at The Watermill Center.