by Gil Troy

Bill Clinton was ambitious, in the best sense of the word. He wanted to use the president’s bully pulpit to make history. He wanted to preserve traditional values with a liberal, open, pro-government but not big-government twist. Clinton had a governing philosophy as comprehensive as Reagan’s – and Clinton’s presidency would be as ideological as Reagan’s. Clinton’s early defining speeches to the centrist Democratic Leadership Council in the mid-1980s, when he launched his campaign in 1991, and at his alma mater Georgetown University, articulated a vision that steered his presidency, trying to find the right mix among three ideas: opportunity, responsibility, community.

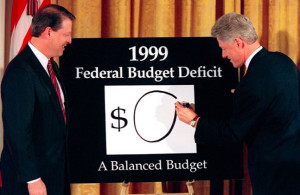

When Clinton was at his worst, he pandered. When he was at his most popular, he triangulated. But when he was at his best, he synthesized, guided by his centrist vision. His ability to fuse Reaganite conservatism and Great Society liberalism, the 1950s and the 1960s, traditional anchors and modern freedoms, the opportunities provided by so many rights and the strong communities that emerged from a suitable sense of responsibility, the Hillbillies and the Yalies, Main Street and Wall Street, America’s superego and America’s id, reflected his and America’s dueling legacies, impulses, and beliefs. Balancing it all properly, constructively, he believed, was “the purpose of prosperity.”

His wife Hillary Rodham Clinton was also trying to shape American attitudes, albeit less successfully. The apple-cheeked, unnaturally-blonde 45-year-old’s blue eyes reflected the fierce intelligence of the overachiever she always was, while her changing hair styles reflected a new insecurity about what kind of First Lady the American people–and press–would let her be. Her “politics of meaning” speech in April, 1993, seeking “a new ethos of individual responsibility and caring” after so much Reaganite “selfishness and greed,” paralleled Bill Clinton’s magnificent November, 1993 speech in Memphis challenging African-American preachers to fight crime by reviving family values. But Bill’s speech was hailed while Hillary’s speech elicited mean-spirited gibes mocking “Saint Hillary.”

Image is in the public domain via AgeofClinton.com

This polarizing First Lady discovered that Americans were less open to challenges from what Nancy Reagan called the “white glove pulpit” with its gossamer shackles, than from the bully pulpit with its mandate to be America’s superman. Hillary Clinton’s attempts to share power as “co-president” would fail. She would, essentially, be “fired” from her public role as Bill Clinton’s sentry–and backbone. The Whitewater, Travelgate, and presidential pardon and furniture-grabbing scandals in 2001 would demonstrate the thickness of the partnership uniting Mr. and Mrs. Clinton privately. Still, her public standing would rise when most Americans saw her as the victim of her husband’s infidelity and when she earned power independently as a senator, rather than commandeering status from her husband.

Bill Clinton was one of the most talented politicians in American history and the man who dominated the 1990s, just as Ronald Reagan dominated the 1980s, and Franklin Roosevelt dominated the 1930s. Not all presidents define their times culturally as well as politically; these three leaders did. And perhaps even more than the 1930s and the 1980s, the 1990s was a time of breathtaking transformation as computers became increasingly networked and portable, taking this revolution viral—computerese for all over. Clinton would describe his primary achievement as “He had to make America work in a new world.”

Image is in the public domain via AgeofClinton.com

Making America work in this new world would not be easy. The greatest change that occurred during Bill Clinton’s tenure had to do with computers going online and being made more portable than ever. These Everything Machines now had nearly infinite reach and were accessible seemingly everywhere. This series of revolutions intensified the modernization processes that had been buffeting America–and the world–since the industrial revolution.

In the Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels diagnosed the destabilizing impact of one of capitalism’s great attributes, its perennial process of reinvention and renewal. By “constantly revolutionizing” the economy, the “whole relations of society” change too, creating “everlasting uncertainty and agitation.” As a result, Marx and Engels argued, tradition, in all its forms, is perpetually threatened with being “swept away.” As if anticipating the American 1960s in 1848 Europe, they wrote: “All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.” Technology and consumerism, both perennially updating and outdating, and each enveloping in its own way, further accelerated the disorientation.

Working off that insight, the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman has identified liquidity as modernity’s defining characteristic. Flexibility, fluidity, immediacy, impulse, individuality, and consumerism, all trump solidity, tradition, patience, responsibility, and communalism. Bauman’s definition of liquid modernity as “the growing conviction that change is the only permanence, and uncertainty the only certainty,” is too absolute. America is a stable country, preserving many continuities and traditions, amid all the innovation. Still, this liquid-solid framing, combined with the Marxian, holy-profane tension, helps explain Bill Clinton, his presidency, and the 1990s.

In the 1990s, the absence of the Cold War’s solidity and solidarity, and the ever-accelerating computer revolution, intensified the sense of weightlessness, of vertigo, of impermanence, of liquidity. Clinton, while seen by Republicans as an unabashed “booster” and the ultimate liquid leader, positioned himself in a more nuanced way, as his Memphis speech demonstrated. As a son of the South, he had a traditional streak, personally and ideologically, which he developed with other Southern moderates in the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC). As a shrewd reader of modern politics, he knew that Democrats would lose if Republicans always trumped them on the three Fs of family, faith and flag. And, as a modern father and husband, he and his wife were trying to integrate some traditional values and structures into the modern life they helped spawn.

Image is in the public domain via AgeofClinton.com

Bill and Hillary Clinton not only stayed married, both believed in the sacred and the solid, a country standing for certain enduring ideals and values. They wanted some liquidity, proud that their increasingly pluralistic country was welcoming women, blacks, gays, immigrants. They feared, as Republicans did, overdoses of freedom, of modernity, where the liquid repeatedly trumped the solid, and the sacred was too frequently profaned. Tragically, Clinton’s moral failings, his impulsivity, threatened this central leadership mission of his, to merge modernity and tradition more smoothly.

The 1990s was a time of tremendous liquidity, when change overwhelmed Americans. Amid those challenges, many Americans appreciated Clinton’s fluidity, his brilliance, his jazz-like improvisational abilities. Clinton wanted to help manage and contain the change. Unfortunately, the traits of openness and adaptability that made him such an effective modern leader, also made him appear to be a political will o’ the wisp, more shapeshifter than ideologue. His private behavior reinforced that assessment of his public role.

In her autobiography, Clinton’s mother, Virginia Clinton Kelley recalled that she and her boys had a “need” to win over any room they entered–wooing the one person in a hundred who might remain resistant until that one has “been enlightened” too. Bernard Nussbaum, Clinton’s first White House Counsel, said that story illustrated Clinton’s greatness as a politician, trying to charm everyone he met, and his weakness as a leader, needing to placate them too. In not just mastering the changes but embodying them, three decades’ worth of cultural and political anxieties stuck to him like gummy sap from an Arkansas Slash Pine evergreen.

One of the many 1990s manifestoes celebrating the newly wired world declared: Technology = Culture and Culture = Technology. This synthesis applies to politics too.

Gil Troy is the author of The Age of Clinton: America in the 1990s, a professor of history at McGill University and a visiting scholar in Governance Studies at the Brookings Institution for the fall of 2015. Originally from Queens, New York, the is the author of ten previous books, including See How They Ran: The Changing Presidential Candidate; Morning in America: How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s; and the award-winning Moynihan’s Moment: America’s Fight Against Zionism as Racism. A weekly columnist for The Daily Beast, he has offered political commentary on all major TV networks in the United States and Canada. His articles have appeared in The New York Times, The New Republic, The Washington Post, The Jerusalem Post, and The Wilson Quarterly, among other major media outlets. Follow him on Twitter at @GilTroy or visit his Web site at www.giltroy.com