by Nick Tabor

Nick Tabor’s Africatown charts the fraught history of America from those who were brought here as slaves but nevertheless established a home for themselves and their descendants, a community which often thrived despite persistent racism and environmental pollution. Read an excerpt below.

yhe

yhe

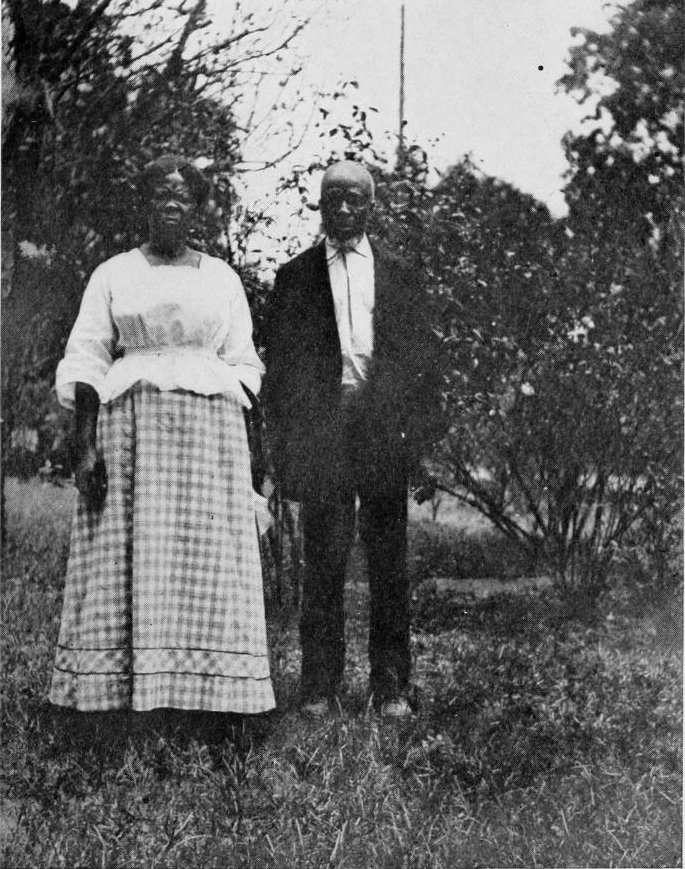

This image is in the public domain.

Joe Womack was waiting for his turn to speak. He was on a stage in Washington, D.C., in the National Geographic Society’s auditorium, facing a crowd of several hundred. He’d flown in the previous night from his home on the Alabama Gulf Coast. The panelists sitting beside him had vaunted pedigrees: one was a famed archaeologist who had spearheaded excavations all over the world; another was a scholar of the African diaspora with a position at Brown University. Womack, for his part, had spent his career as an accountant and truck driver. But in his retirement, he’d found another calling.

They were there to discuss the Clotilda, the last slave ship ever brought from West African to American shores. A year earlier, archaeologists had announced that after an exhaustive survey, they had identified the wreckage of the Clotilda in the Mobile Delta. The story of the ship’s voyage is not widely known and has rarely appeared in history books, but Womack had known about it as long as he could remember. The neighborhood where he grew up, outside the city of Mobile, was settled by the slave ship’s survivors.

That story—as it was narrated onstage that night, more or less—goes like this. In the late 1850s, throughout the Deep South, demand for enslaved workers was incredibly high. The federal government had long since made it illegal to import slaves from West Africa. But Timothy Meaher, a business magnate and riverboat captain who lived outside of Mobile, hatched a plan to bring a slave ship in nevertheless. His cargo arrived in 1860, nine months before the Civil War began. The victims were 110 men, women, and children who were brought on the Middle Passage.

Five years later, after the Civil War ended, these West Africans were freed, but they had no way of getting back home. They were marooned in a foreign land. Several dozen of them, making the best of their situation, saved their wages and bought land in a remote region outside of Mobile, where they established a little community of their own. They married among themselves, appointed leaders, and lived according to their own customs. Their settlement came to be known as African Town. Over time, hundreds of American-born Black people moved there, and the shipmates’ descendants mixed with the newcomers. All these decades later, the neighborhood still survives, now within Mobile’s city limits; and many of the residents can trace their lineage back to the slave ship. The name has been shortened to Africatown.

Womack is not a descendant, at least as far as he knows; but he was born only fifteen years after the last shipmate in Mobile County passed away, and he grew up hearing stories about the West Africans. Traces of their presence were still evident when he was a child. The church the shipmates had built and the cemetery where some of them were buried were each a short walk from his home. Throughout his life, there had also been rumors that the Clotilda’s wreckage was still in the Mobile River and could be seen at low tide.

In 2018, archaeologists pinpointed a section of the Mobile Delta that served long ago as a “ship graveyard,” where captains had once hauled old vessels and abandoned them. Ultimately, the crew singled out one wreck that matched the Clotilda’s dimensions precisely. In 2019, after months’ worth of research and peer review, the crew’s leader, James Delgado, announced that the slave ship had been identified “beyond reasonable doubt.”

The event that evening in early 2020 was billed “Finding the Clotilda: America’s Final Slave Ship,” but Womack and Joycelyn Davis, his travel companion and frequent collaborator, were there to speak about the Africatown community as it still existed. Davis, a teaching assistant in her forties, was asked to speak first. She was a sixth-generation descendant of Oluale, or Charlie Lewis, one of the Clotilda’s survivors. Since the identification of the ship, Davis had been helping to run an association for fellow descendants.

“Growing up in Africatown,” she said, “I feel like my family—my grandma, my great-grandma—carried on the traditions of Charlie Lewis.” She spoke about Lewis Quarters, the section where her ancestor had bought land and built a house in 1870. It was still inhabited by her family, and growing up, Davis had spent her Saturdays there, with an older relative teaching her the family history. When the Clotilda news had been announced, Davis said, she had imagined how it must have felt to be stuck in the ship’s hold for six weeks. It gave her chills. “Finding the ship has been a great thing,” she said, “but it’s about the people, to me.” She hoped the news about the ship would lead to better conditions for the families that remained in the neighborhood.

In the present day, Africatown is no longer bordered directly by rivers and lush forests. Instead, it’s hedged in by a chemical plant, a pipe manufacturing plant, a power plant, a tissue mill, a refinery, and a scrap-metal shop, among other industrial businesses. A rock quarry backs up against one section of the neighborhood; and the only way to get in or out of Lewis Quarters is to drive through a lumber mill. Pollution is rampant. Moreover, the business district that Davis and Womack knew as children, which was once lined with the shops of local Black entrepreneurs, has since been replaced with a five-lane highway, designed for trucks carrying hazardous cargo. It is impossible to buy even a bottle of water without leaving the area.

The moderator turned her attention to Womack. She asked him to speak about “some of the concerns and some of the work” happening in Africatown.

“My involvement with the community consists of three things—” he said, “protect, preserve, and prolong.” He wore a scarf with an orange and green ankara pattern and a tan sport coat. Behind him, a detailed digital replica of the Clotilda was shown on a giant screen. The protection part of his work, he said, was about fending off new incursions by heavy industry. He explained that when he was a child, there had been two enormous paper mills, International Paper and Scott Paper, bookending the residential zone. It was not uncommon in those years for ash to blow from one factory or the other. “Those of you who are over the age of fifty probably remember the old sixteen-ounce Coca-Cola drink,” he said. “Ash falls in your drink, and you try to turn it up and turn it out.” He made a tilting gesture. “The ashes went this way, and you’d lose all your soda. So how do you get rid of it? You know, you’re twelve years old, you got a drink that cost you all of your money, six cents. How do you get rid of that ash? You shake it up. It foams, and you look at it, ain’t there, so you drink it.” He made a drinking motion. “Most of my friends that were born after 1945 are not living today.”

There were gasps throughout the auditorium.

rfgg

rfgg

Leigh T. Harrell)This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

“People talk about statues, about the historic statues,” he went on. It seemed to him that while African Americans didn’t have many statues honoring their contributions to history, they did have historical sites that were still intact—and Africatown was one of these. “The cemetery, the people, the community—these are the monuments that we have to save,” he said, “not only for the sake of the community, but for the sake of the world.”

Womack brought up the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which had opened in Montgomery in 2018. It commemorates the victims of lynching in America. The presentation is stark and unsettling; but within a year of its opening, the memorial had attracted some 400,000 visitors from around the world and had brought nearly $1 billion in economic activity to Montgomery. Womack said its success gave him hope; he and Davis and their allies saw it as a model of what Africatown could become. But there was one major obstacle, he concluded. “Unfortunately, the same people who brought us over are still in charge.”

Copyright © 2023 by Nick Tabor

Nick Tabor is a freelance journalist whose work has appeared in New York Magazine, The New Republic, The Washington Post, Oxford American, The Paris Review, and elsewhere. Africatown is his first book. He lives in New York.