by Tom Clavin

Previously, I discussed Simon Kenton, friend to Daniel Boone and fellow legendary frontiersman. Today, it’s the turn of Daniel Morgan, another one of the colorful, larger-than-life characters to be found in Blood and Treasure: Daniel Boone and the Fight for America’s First Frontier by Bob Drury and yours truly.

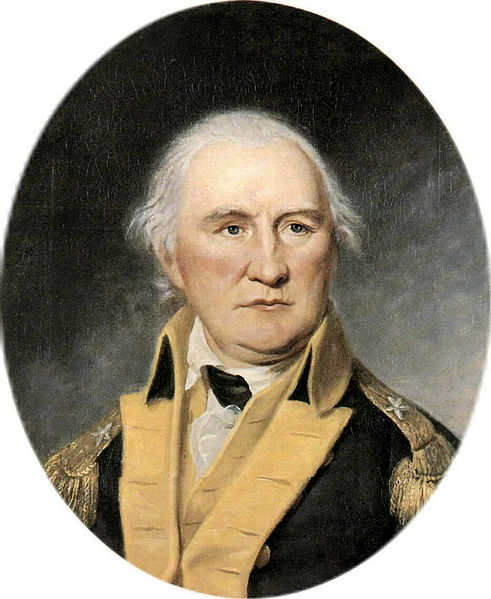

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Boone and Morgan were cousins but as far as we know did not meet until both were participants in an ill-fated expedition in 1755 by British troops to capture a French fort. Late that May, Gen. Edward Braddock departed Fort Cumberland in western Maryland at the head of 1400 British regulars and between 300 and 400 militia auxiliaries from Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina. The nominal leaders among the colonials were the Virginians, whose governor had initially raised the call to arms to the neighboring colonies. But, in truth, Braddock and his inner circle regarded the provincials as little more than camp labor—even militia officers such as Col. George Washington were treated as second-class soldiers. As such, sharpshooters like Daniel Boone were assigned to the rear of the column as waggoneers hauling the regimental baggage. Braddock’s target, Fort Duquesne, rose 110 miles to the west.

At 19, Daniel Morgan was almost two years Boone’s junior. That Morgan was descended from the same Welsh stock as Sarah Morgan Boone (Daniel’s mother) was evident. Well over six feet tall and broad of shoulder with a frontiersman’s ruddy complexion, the leonine Morgan towered over his cousin. Morgan had migrated from New Jersey to Virginia two years earlier, and had since worked clearing land, operating a sawmill, and hiring out as a teamster. Though technically unschooled, he possessed an uncanny business acumen, and by the time of Braddock’s expedition he had put aside enough money to purchase his own wagon and draft team, which the British had conscripted for the campaign.

Morgan’s reputation as a roustabout across Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley equaled Boone’s renown as a tracker and hunter along North Carolina’s Blue Ridge. He was known to walk into one of the motley public houses that dotted the Shenandoah and challenge any and all comers to a wrestling match. He rarely lost. The rough company Morgan kept along America’s borderlands can be ascertained from a letter to The Virginia Gazette from an itinerant preached published in 1751. The clergyman, whose sensibilities had been refined in the east, was aghast at the rampant immorality inherent to the liquor-purveying “Ordinaries.” Like so many of his fellow citizens, he viewed the unruly westerners as barely a step above wild savages in manners, clothing, and taste. Their backwoods barrooms, he wrote, “are the common Receptacle and Rendezvous of the very Dreggs [sic] of the people, even of the most lazy and dissolute where Time and Money are vainly and unprofitably squandered away, where prohibited and unlawful Games, Sports, and Pastimes are used, followed, and practiced almost without any intermission; namely Cards, Dice, Horse-racing, and Cock-fighting, together with Vices and Enormities of every other Kind.” To the irate cleric, this may have been literal hell on earth. To Dan Morgan, it was a night out.

On the morning of July 9, Braddock’s troops forded the Monongahela River. Following the rigid military formations more suited to the open battlefields of Europe—and pointedly ignoring the American militia officers who pleaded with him to fan scouts out to either flank—Braddock arrayed his soldiers with colors flying, drums beating, and fifes playing. Soon they were approaching a twisting forest path that descended into the thick and dank timberland leading to the fort. The Americans, Boone among them, were certain that they were walking into a trap.

Fort Duquesne’s French commander was aware that his barely completed stockade could not withstand an artillery bombardment. To that end, he had left a small rearguard at the fort while he and his soldiers and Indian allies left under cover of darkness and positioned themselves among the bushes, fallen logs, wild tall grass, and massive oak trees, some of them 50 feet in diameter, on either side of the British pathway. The resultant ambush turned the trail into an escape-proof enclosure. Braddock’s forward companies were cut down within moments, and as the main body of his army huddled in utter bewilderment, they too were picked apart by the musket balls and arrows of an unseen enemy.

Despite this suicidal error in judgment, it should be noted that all first-person accounts of the massacre—including a thorough After-Action report penned by George Washington—described the gallantry with which the British officers, most notably Braddock himself, attempted to re-form their troops into both offensive and defensive postures. Most of these officers, in the words of one eyewitness, “were sacrificed by the soldiers who declined to follow them, and even fired upon them from the rear.” In a matter of moments, the panicking Redcoats “broke and ran like sheep before the hounds.” Braddock was one of the last to fall when a ball passed through his right arm and lodged in his lung. He fell from his horse and was carried from the field by, among others, the young Washington. He would die from the wound four days later.

Meanwhile, as war cries echoed through the trees and Indians darted from the woods to lift the scalps of fallen Redcoats, the ripping-silk sounds of musket balls cleaving the air began to encompass Boone, Morgan, and their fellow American teamsters a half-mile to the rear. Boone fired off several rounds at the approaching mass of French and Indians before cutting his team’s lead horse loose from its harness, jumping on its back, and plunging into the surrounding forest.

Morgan was not as fortunate. As he leaped from his lazy board and attempted to slice his horses’ reins, a ball punctured the back of his neck and exited his left cheek, taking with it his upper and lower molars. The wound did not immobilize Morgan, and while the Indians paused to plunder the baggage train, he and Boone managed to join the jangled survivors falling back across the Monongahela.

During three hours of fighting of “Braddock’s Folly,” 26 British and colonial militia officers were killed and another 37 wounded, while 714 British privates and non-commissioned officers were slain. These included 12 British captives whom the Indians marched back to Fort Duquesne, staked to poles on the banks of the Alleghany, and burned alive one by one. The fort’s French commander later testified that he was helpless to stop the gruesome executions.

In the wake of the encounter, the highest-ranking British officer left standing was Col. Washington, who managed to rally a small company of Virginia militiamen to cover the retreat. Two horses were shot from beneath Washington during the withdrawal, and another four balls pierced his greatcoat and hat. It is likely that Boone crossed paths with Washington during the trek back east, and Boone’s youngest son would later mention that his father had met the future president on that mission.

Daniel Morgan would recover from his nasty wound and become a hero of the American Revolution. He fought in several engagements, and in October 1780, he was promoted to brigadier general, serving under Gen. Nathaniel Greene in North Carolina. Greene gave Morgan command of about 600 men and the job of foraging and enemy harassment in the backcountry of South Carolina.

The British General Cornwallis sent Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion to track him down. Morgan talked with many of the militia who had fought Tarleton before and decided to set up a direct confrontation. He chose to make his stand at Cowpens, and on the morning of January 17, 1781, a pivotal battle took place there. Morgan’s plan took advantage of Tarleton’s tendency for quick action as well as the longer range and accuracy of his Virginia riflemen. The marksmen were positioned to the front, followed by the militia, with the regulars at the hilltop. The first two units were to withdraw as soon as they were seriously threatened, but after inflicting damage. This would invite a premature charge from the British.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

As the British forces approached, the Americans, with their backs turned to the British, reloaded their muskets. When the British got close to the Americans, they turned and fired at point-blank range in their faces. In less than an hour, Tarleton’s 1,076 men suffered 110 killed and 830 captured, with 200 of the latter wounded. The British Legion, among the best units in Cornwallis’s army, was effectively disbanded. Cornwallis had lost not only Tarleton’s legion but also his light infantry, which limited his speed of reaction for the rest of the campaign, which would end at Yorktown.

For his actions, Virginia gave Morgan land and an estate that had been abandoned by a Tory. In July 1781, Morgan briefly joined the Marquis de Lafayette to pursue Banastre Tarleton once more, this time in Virginia, but they were unsuccessful.

Morgan resigned his commission after having served six-and-a-half years, and at 46 returned home to Frederick County. He turned his attention to investing in land and eventually built an estate of more than 250,000 acres. As part of his settling down in 1782, he joined the Presbyterian Church and, using Hessian prisoners of war, built a new house near Winchester, Virginia. Morgan named the home Saratoga after the victory in New York where he had played a prominent role. The Congress awarded him a gold medal in 1790 to commemorate his victory at Cowpens.

In 1794, Morgan was briefly recalled to national service to help suppress the Whiskey Rebellion, and the same year he was promoted to major general. Serving under General “Light Horse Harry” Lee, Morgan led one wing of the militia army into western Pennsylvania. The massive show of force brought an end to the protests without a shot being fired. By the way, one of his officers was the future explorer Meriwether Lewis.

Morgan ran for election to the U.S. House of Representatives twice. He lost in 1794 but won in 1796 with 70% of the vote. He served a single term from 1797 to 1799. Morgan died at his daughter’s home in Winchester on July 6, 1802, and was buried in Old Stone Presbyterian Church graveyard.

Originally published on Tom Clavin’s The Overlook.

Tom Clavin is a #1 New York Times bestselling author and has worked as a newspaper editor, magazine writer, TV and radio commentator, and a reporter for The New York Times. He has received awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, and National Newspaper Association. His books include the bestselling Frontier Lawmen trilogy—Wild Bill, Dodge City, and Tombstone—and Blood and Treasure with Bob Drury. He lives in Sag Harbor, NY.