By Mark Stille

Japan’s approach in 1941, which consisted of negotiations in parallel with preparations for war, never gave the negotiations any realistic chance of success unless the United States agreed to Japan’s conditions. Thus, increasingly, war became the only remaining option. An Imperial Conference on July 2, 1941, confirmed the decision to attack the Western powers. In early September, the Emperor declined to overrule the decision to go to war and the final authorization for war was given on December 1. By this time, Yamamoto’s Pearl Harbor attack force was already at sea.

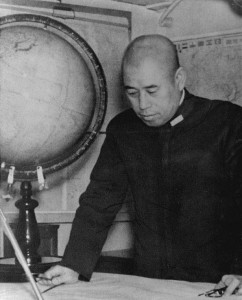

Yamamoto alone came up with the idea of including the Pearl Harbor attack into Japan’s war plans and, because the attack was so risky, it took great perseverance on his part to get it approved. It says much for his influence and powers of persuasion that the event even occurred. The attack was successful beyond all expectations, making it central to Yamamoto’s reputation as a great admiral, and as it had strategic and political ramifications far beyond what he imagined, it made Yamamoto one of World War II’s most important commanders.

Yamamoto was not the first person to think of attacking the American naval base at Pearl Harbor. As early as 1927, war games at the Japanese Navy War College included an examination of a carrier raid against Pearl Harbor. The following year, a certain Captain Yamamoto lectured on the same topic. By the time the United States moved the Pacific Fleet from the West Coast to Pearl Harbor in May 1940, Yamamoto was already exploring how to execute such a bold operation. According to the chief of staff of the Combined Fleet, Vice Admiral Fukudome Shigeru, Yamamoto first discussed an attack on Pearl Harbor in March or April 1940. This clearly indicates that Yamamoto did not copy the idea of attacking a fleet in its base after observing the British carrier raid on the Italian base at Taranto in November 1940. After the completion of the Combined Fleet’s annual maneuvers in the fall of 1940, Yamamoto told Fukudome to direct Rear Admiral Onishi Takijiro to study a Pearl Harbor attack under the utmost secrecy. After the Taranto attack, Yamamoto wrote to a fellow admiral and friend stating that he had decided to launch the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1940.

If it is to be believed that Yamamoto decided on his daring attack as early as December 1940, several issues are brought into focus. First and foremost, it can be established that Yamamoto had decided on this risky course of action even before the advantages and disadvantages of such an action could be fully weighed. Also, in late 1940, Yamamoto did not even possess the technical means to mount such an operation. Another question that needs to be asked is why Yamamoto thought it was his job to formulate grand naval strategy, which was the responsibility of the Naval General Staff.

The planning for the attack was a confused and often haphazard process. In the beginning, there was only Yamamoto’s vision. Gradually, and against almost universal opposition, Yamamoto made his vision become reality. In a letter dated January 7, 1941, Yamamoto ordered Onishi to study his proposal. This was followed by a meeting between Yamamoto and Onishi on January 26 or 27 during which Yamamoto explained his ideas. Onishi was selected by Yamamoto to develop the idea since he was the chief of staff of the land-based 11th Air Fleet and was a fellow air advocate and a noted tactical expert and planner.

Onishi pulled Commander Genda Minoru into the planning in February. After Genda was shown Yamamoto’s letter, his initial reaction was that the operation would be difficult, but not impossible. With Yamamoto providing the driving vision and political top-cover, Genda became the driving force in actually turning the vision into a viable plan. Genda believed that secrecy was an essential ingredient of planning and that to have any chance of success, all the IJN’s carriers would have to be allocated to the operation. Genda was charged with completing a study of the proposed operation in seven to ten days. The subsequent report was a landmark event in the planning process since most of his ideas were reflected in the final plan. Onishi presented an expanded draft of Genda’s plan to Yamamoto on about March 10.

On November 15, 1940, Yamamoto had been promoted to full admiral and, as the planning for war increased in intensity, he began to wonder about his future. It was customary for the Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet to serve for two years. In early 1941, Yamamoto was thinking of his impending change of duty and was pondering retirement. He would have liked to have been appointed commander of the First Air Fleet (the IJN’s carrier force), to lead his bold attack, but realized that such an event was impossible. During this time, he told one of his friends:

If there’s a war, it won’t be the kind where battleships sally forth in a leisurely fashion as in the past, and the proper thing for the C. in C. of the Combined Fleet would be, I think, to sit tight in the Inland Sea, keeping an eye on the situation as a whole. But I can’t see myself doing anything so boring, and I’d like to get Yonai to take over, so that if the need arose I could play a more active role.

In spite of his desires, Yamamoto did not leave his post in mid-1941 after his two years were up.

Yamamoto Takes On the Naval General Staff

Perhaps harder than resolving any technical and operational difficulties to make the attack on Pearl Harbor possible was Yamamoto’s task of convincing the Naval General Staff that the Pearl Harbor operation was viable. Since the Naval General Staff had responsibility for the overall formulation of naval strategy, any questions about whether, and how, to attack the United States in the initial phase of the war clearly fell under its jurisdiction. However, in another indication of the muddled Japanese planning process, Yamamoto wanted to seize this prerogative for himself. In late April, Yamamoto entrusted one of his principal Combined Fleet staff officers to begin the process of convincing the skeptical Naval General Staff. The initial meeting did not go well for Yamamoto since the Naval General Staff did not believe his contention that the attack would be so devastating that it would undermine American morale. The focus of the Naval General Staff was on guaranteeing the success of the southern operation and this required the use of the Combined Fleet’s carriers. Their biggest concern was that the Pearl Harbor attack was simply too risky. In order to gain the Naval General Staff’s approval, Yamamoto began to stress the fact that his Pearl Harbor attack would also serve to guard the flank of the southern advance by crippling the Pacific Fleet at its principal base.

In August, the same staff officer returned to Tokyo to plead Yamamoto’s case. Though the Naval General Staff remained opposed to the idea, it did agree that the annual war games would include an examination of the Pearl Harbor plan. These began on September 11 with the first phase focusing on the conduct of the southern operation. On September 16, a group of officers selected by Yamamoto, including representatives of the Naval General Staff, began a review of the Hawaii operation. The results of this controlled tabletop maneuver seemed to confirm that the operation was feasible, but also served to confirm that it was risky and that success depended heavily on surprise. At the end of the two-day exercise, the Naval General Staff remained unconvinced. Basic concerns, such as whether refueling was possible to get the entire force to Hawaii and how many carriers were to be allocated to the operation, also remained unresolved.

On September 24, the Operations Staff of the Naval General Staff held a conference on the proposed Hawaii attack. Yamamoto became enraged when he learned that once again the Naval General Staff had rejected his plan. On October 13, the Combined Fleet’s staff held another round of table maneuvers on Yamamoto’s flagship, the battleship Nagato, to refine aspects of the Pearl Harbor operation and toreview the southern operation. Only three of the IJN’s fleet carriers were used, Kaga, Zuikaku, and Shokaku, because they had the range to sail to Pearl Harbor; the other three fleet carriers, Akagi, Soryu, and Hiryu were allocated to the southern operation. For the first time, fleet and midget submarines were included in the planning for the Pearl Harbor attack. The next day, there was a conference to review the plan, and where all admirals present were invited to speak. All but one was opposed to the Pearl Harbor attack. When they were done, Yamamoto addressed the assembled group and stated that as long as he was in charge, Pearl Harbor would be attacked. The time for dissension and doubt among the Combined Fleet’s admirals was finished.

With the support of his own commanders assured, Yamamoto was determined to bring the issue to a head with the still skeptical Naval General Staff. In a series of meetings on October 17–18, Yamamoto played his ace card. His staff representatives revealed that unless the plan was approved in its entirety Yamamoto and the entire staff of the Combined Fleet would resign. Since to Nagano the notion of going to war without Yamamoto at the helm of the Combined Fleet was simply unthinkable, this threat served to bring the Pearl Harbor debate to a close. In the end, it was not logic that carried the day for Yamamoto, but the threat of resignation and it was not to be the last time that he would use this tactic.

The staff of the First Air Fleet conducted the actual planning for the operation. On April 10, 1941, Yamamoto had given the go-ahead to form the First Air Fleet by combining Divisions 1 and 2 into a single formation. This was a revolutionary step which had been considered for some time, and in April Yamamoto judged that the time was right to take that step. As an air power advocate, he felt it was necessary to maximize the striking power of the carrier force. By concentrating the carriers into a single force, Yamamoto had created the most powerful naval force in the Pacific and gained the means by which to conduct his Pearl Harbor operation. By late April, the staff of the new First Air Fleet, led by Genda, who had been assigned as staff air officer, was engaged in fleshing out the details of the operation. Gradually, the problems associated with refueling, executing torpedo attacks in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor, and making level bombing against heavily armored battleships a viable tactic, were solved.

The Pearl Harbor Plan

For Yamamoto, the purpose of the Pearl Harbor attack was to sink battleships rather than carriers. Battleships were so deeply entrenched in the minds of the American public as a symbol of naval power that by shattering their battle fleet Yamamoto believed American morale would be crushed. He even considered giving up the entire operation when it appeared that the problem of using torpedoes in the shallow harbor could not be solved – torpedoes were required to sink the heavily armored battleships, whereas dive-bombing would have sufficed to sink the lightly armored carriers. This emphasis on the targeting of battleships rather than carriers calls into question Yamamoto’s credentials as a strategic planner as well as his status as a true air power advocate.

The final plan was completed by Genda and reflected the difference in opinion between Genda and Yamamoto. Genda, the air power zealot, devoted more weight to sinking carriers, and less to sinking battleships. The first wave of the attack included 40 torpedo planes which were broken down into 16 against the two carriers that might be present, and the other 24 against as many as six battleships, which were vulnerable to torpedo attack. Fifty level bombers carrying specially modified armor-piercing bombs were also allocated to attack the so-called “Battleship Row” where most of the battleships were berthed. Level attack was the only way to strike inboard areas of the battleships when two ships were moored together. Fifty-four dive-bombers and the escorting fighters were ordered to attack the many airfields on Oahu. In all, the six carriers in the attack force planned to use 189 aircraft in the first wave.

The second wave was planned to comprise 171 aircraft. The 81 dive-bombers were the centerpiece of this group and were given orders to concentrate on completing the destruction of any carriers present, followed by attacks on cruisers. The relatively small bombs carried by the dive-bombers were insufficient to penetrate battleship armor, so the first wave had the job of inflicting maximum damage on the heavy ships. The remainder of the second wave aircraft, which included 54 level bombers, was to complete the destruction of American air power on Oahu in order to prevent any return strikes on the Japanese carriers.

Despite the fact that the strikeforce (the Kido Butai) embarked at least 411 aircraft for the operation, making it the most powerful naval force in the Pacific, the attack remained a risky undertaking. If the Americans detected the raiders in time to prepare their air defenses, the attack could be catastrophic for the Japanese, a fact they had ascertained in their pre-attack gaming. If exposed to counterattack, the Japanese carriers were vulnerable. Nagumo Chuichi had under his control a large portion of the IJN’s striking power, and to lose the force on the first day of the war would be a disaster.

The Pearl Harbor Raid

The Kido Butai departed its anchorage in the Kurile Islands on November 26. The transit was undetected and by the morning of December 7, from a position some 200 miles north of Oahu, six Japanese carriers had begun to launch the first attack wave. At 0753hrs the strike leader sent the signal “Tora, Tora, Tora,” indicating that the element of surprise had been gained.

Excerpted from Yamamoto Isoroku by Mark Stille.

Copyright 2012 by Osprey Publishing.

Reprinted with permission from Osprey Publishing.

MARK STILLE (Commander, United States Navy, retired) is the author of Yamamoto Isoroku, The Coral Sea 1942 and numerous other books focusing on naval history in the Pacific. He received his BA in History from the University of Maryland and also holds an MA from the Naval War College. He has worked in the intelligence community for 30 years including tours on the faculty of the Naval War College, on the Joint Staff and on US Navy ships. He is currently a senior analyst working in the Washington, D.C. area