by Mary Jo McConahay

Of all the fighting units struggling toward the final liberation of Italy, the men of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force are among the most warmly remembered in the towns and villages of the Apuan Alps and the Apennines, where they freed towns from occupying fascists. On local commemorations of the end of the war in the north three flags may fly: The Italian Tricolore, the U.S. Stars and Stripes, and the striking blue, green and gold banner of Brazil. With the passage of time the Brazilian Smoking Cobras, however, are largely forgotten in their own country, and rarely appear in Allied accounts of the war.

Nevertheless, the only Latin American unit thrown up against the Reich in Europe possesses a history as rich and dramatic as any other troops: twenty-five thousand underprepared men who arrived late and were battered by early losses in the field, but ended the war as a band of brothers with significant victories to call their own.

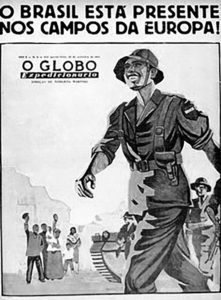

Credit: O Globo, Rio de Janeiro

“The Brazilians will go to war when the snake smokes,” Hitler is reputed to have said, dismissing the possibility that the far-away, pro-fascist dictatorship of Gen. Getulio Vargas would commit troops to the European theatre, let alone to the Allied side. By 1943, however, President Roosevelt had cajoled the biggest country in South America with the promise of U.S. assistance to post-war industrial development – a Vargas dream; Rio allowed the U.S. Navy to begin building airstrips and bases on the strategic Brazilian hump, only 1800 miles from the closest city in Africa – Dakar; and U-boats began to sink Vargas’ ships. The die was cast. In July, 1944, the first ships from Rio arrived in Naples, and the Brazilians found themselves learning about U.S. arms under U.S. trainers at an old royal hunting ground outside Pisa. In a challenge to the Fuehrer, they called themselves the “Smoking Cobras” and sewed insignia of green and gold onto their sleeves. The patches carried an image of a rising cobra with a pipe in its mouth, smoke wafting up from the bowl.

When the Brazilians arrived 1944 Allies had occupied Italy south of the Arno River, but the country north of the river was still in enemy hands. The region was defended by the Gothic Line, 180 miles of iron, tank traps and sniper towers designed to be impregnable.

Lt. General Euclides Zenóbio, a charismatic 51-year old officer, led the assault that gave the Smoking Cobras their first victory, taking back from the enemy the town in western Tuscany called Camaoire. “He did not waste time,” the Brazilian chief of Staff, Floriano de Lima Brayner wrote. Zenóbio commanded “with bits of recklessness…not worrying about the dangers surrounding him.”

The Brazilians succeeded joyfully at Camaiore, but in general they lost more skirmishes to the Germans than they won in their first weeks in the field. Churchill had been wrong to say the Germans would not fight for Italy. Only when the Smoking Cobras crossed into the Serchio River Valley did they begin to come into their own. Zenóbio led the men town by town toward the Northern Apennines, which the historian of the Fifth Army, to which the Brazilians were attached, has called “the most formidable mountain barrier [the Fifth Army] was ever to face in combat operations in Italy.” Unfortunately, the advance was a miserable slog: seasonal rains came down in torrents, trucks slid from the roads, soldiers on foot were prey to flash floods and mud so deep it could swallow a man.

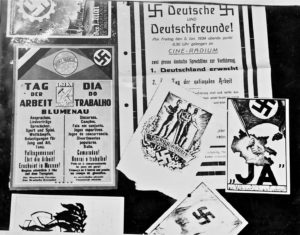

Credit: Fundaçao Cultural de Blumenau

The Brazilians found the Serchio Valley towns occupied by the Germans, or elements of the Italian Black Brigade, loyal to Mussolini. Not far away, fascist troops slaughtered civilians, sometimes as warnings for suspected collaboration with the Italian partisans. In a hill town called Sant’Anna de Stazzema, SS troops took reprisals for one partisan operation by murdering 700 residents, including 130 children, and burning their bodies. A local priest in the town of occupied Barga, a walled city 25 miles from the massacre, wrote that his flock looked “like anyone with a loved one dying.”

As the Allies approached Barga in numbers, however, the Germans and Italians retreated to nearby hills. On October 11, 1944 townspeople cheered as the Brazilians entered triumphally in jeeps. Too triumphally. “Get out of the streets!” someone yelled, perhaps one of the partisans who had entered the town two days before. Enemy fire rained down from the hills.

For weeks, the Brazilians and other allied troops fought to root out the enemy, liberating more towns. One night in November they moved by truck 75 miles east and north of the Serchio Valley to a new frontline in sight of a 3,240-foot-high rise, Monte Castello. Many of the South Americans stared in wonder when the first snow fell because they had seen the white flakes descend and pile up in drifts only in movies, or in their dreams. Soon the snow meant not enchantment but frostbite, rotting feet, burning skin.

Ferocious cold or not, the commander of the expeditionary force, Joâo Baptista Mascarenhas de Moraes, was determined his men would do their country – and himself – proud. German Field Marshal Albert Kesserling described Monte Castello as “of maximum importance for the possession of Bologna and the routes of communication toward the south, north and northwest.” The Brazilians’ new orders from Allied headquarters: take the mountain. Thus Mascarenhas began the trial by fire that finally forged the Smoking Cobras into seasoned fighters.

For the next months, Monte Castello loomed before the Smoking Cobras like Ahab’s white whale, taunting, seemingly unconquerable, yet something that must be mastered no matter what the cost. They threw themselves at the mountain in November, December and January, without success. One battalion failed to perform reconnaissance, and became sitting ducks for the Germans. On another day, rain turned the slopes into fatal marshes; forty-nine Brazilians died. Finally, on their fifth attempt, on February 21, 1945, the Brazilians launched an assault by way of the mountain’s flanks, not frontally as they had done before. As dark fell, Zenobio placed a call to Mascarenas. “The mountain is ours,” he said.

Buoyed by success, the Smoking Cobras became unstoppable, ending the war by taking the surrender of the entire 148th division of the German army. Commemorative plaques can be found today in Italian towns the Brazilians liberated during the war, some engraved by locals with the image of a rising snake confidently smoking a pipe.

BONUS – Watch the book trailer for The Tango War:

Born in Chicago, MARY JO MCCONAHAY is an award-winning reporter who covered the wars in Central America and economics in the Middle East. She has traveled in seventy countries and has been fascinated by the history of World War II since childhood, when she listened to the stories of her father, a veteran U.S. Navy officer. A graduate of the University of California in Berkeley, she covers Latin America as an independent journalist. Her previous books include Maya Road and Ricochet. She lives in San Francisco.