by Giles Milton

The greatest heroes of the Second World War are rightly celebrated for their acts of extraordinary daring on the battlefields of Nazi-occupied Europe. Rather less well known are the heroes of the early Cold War—American and British—who fought a perilous secret war against the Soviets in the broken ruins of Berlin.

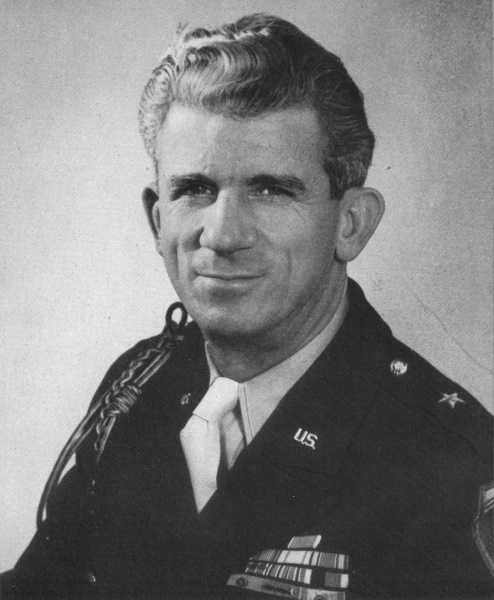

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

The most colourful of these forgotten heroes is Col. Frank ‘Howlin’ Mad’ Howley, who rose to become commandant of the American sector of the divided German capital. Implacably opposed to his Soviet counterpart, he was the first to realize that America’s wartime alliance with Stalin had run its course. The Soviet Union had gone from friend to foe, and Col. Howley was to spend the next four years fighting a deeply personal battle against his Soviet opposite number, General Alexander Kotikov.

Colonel Howley was a living legend to the men serving under him, a blunt-spoken Yankee with a dangerous smile and a disarmingly sharp brain. During the war he had commanded an outfit named A1A1, splendid shorthand for a unit led by such a high-spirited adventurer. The task of this unit was to sweep into newly liberated territories and impose order on chaos, repairing shattered infrastructure and feeding starving civilians.

He was busy running food supplies into Paris when visited by the American commander, Brigadier-General Julius Holmes.

‘Frank,’ asked Holmes, ‘how would you like to go to Berlin?’

‘Fine,’ shrugged Howley. ‘I’d like to stay on the main line east.’ This brief exchange was all it took for him to land one of the biggest jobs in the post-war world.

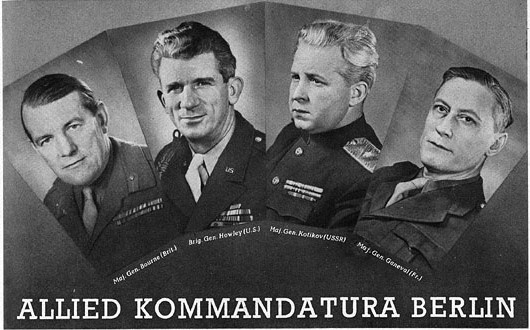

Howley and his men arrived in the wrecked German capital at the beginning of July 1945. Although each commandant was responsible for their own sector—American, British, French and Russian—they met regularly to discuss matters affecting the city as a whole. And it was here, at the Kommandatura, that Howley first met his opposite number, General Alexander Kotikov.

The American colonel did not trust the Soviets from the moment he arrived in Berlin—and with good reason. In the two months before his arrival, the Soviets had looted and raped on a terrifying scale. Howley viewed them as lawless bandits. ‘There is only one way to deal with gangsters, Russian-uniformed or otherwise,’ he wrote in his diary, ‘and that is to treat them like gangsters.’

Col Howley was soon receiving secret intelligence from the Soviet sector of the city: this suggested that General Kotikov was intent on kicking the western allies out of their areas of the city. Howley was alarmed. ‘I had come to Berlin with the idea that the Germans were the enemies,’ he wrote. ‘[But] it was becoming more evident by the day that it was the Russians who really were our enemies.’

Enemy number one was Kotikov himself, who was indeed hoping to evict the western allies, on the direct orders of Stalin. Thus began a titanic battle of wills between Howley and Kotikov, who both realised that the future of the post-war world was at stake. Soviet-backed newspapers began to refer to Howley as ‘the brute colonel’ or ‘the Beast of Berlin,’ monikers that brought Howley considerable pride.

For more than a year, President Truman urged Howley to work alongside his Soviet colleagues, reminding him that America wanted to retain its successful wartime alliance with Stalin. But Howley did everything in his power to bring about a change in policy.

Eventually, American foreign policy would swing behind Howley’s way of thinking, with the president announcing his Truman Doctrine and George Marshall announcing his Marshall Plan. The former sought to contain Communism; the latter sought to rebuild Europe’s shattered economies.

Matters would reach crisis point in June 1948, when the Soviets blockaded the western sectors of Berlin in a dramatic attempt to drive the allies out of the city. They seized control of the road and rail routes into Berlin and refused to allow the Americans and British any access.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Howley was determined that the Americans and British would remain in the city, proposing that they fly in supplies from their sectors of occupied Western Germany. ‘We’ll starve, we’ll eat rats, rather than quit Berlin!’

But there was no need to eat rats, for Howley became a steadfast champion of the Berlin Airlift. Each day, thousands of tons of food and supplies were delivered by air to the city’s western sectors. Aircraft flew into Berlin at five different altitudes and at intervals of 500 feet, with planes taking off and landing every ninety seconds. This enabled 480 planes to land each day at Tempelhof, the principal American airfield. They landed some 4,500 tons of food in any given 24-hour period—just enough to keep Berliners from starvation.

Stalin believed a prolonged airlift to be unsustainable, but Howley urged his airmen to ever greater feats. He was aided by the logistical wizardry of General William ‘Tonnage’ Tunner, director of the airlift. By May 1949, American and British planes were flying in up to 12,000 tons a day. Sensing defeat, Stalin dramatically called off the airlift. It was a humiliating climbdown. For ‘Howlin’ Mad’ Howley, it was his greatest moment of triumph. He, more than anyone, had helped to save Berlin from the Soviets.

‘Here’s to the Yanks,’ he wrote in his memoir, ‘who, working day and night with our British and French allies and with democratic Germans, made the Berlin victory possible.’

He praised the garrison soldiers of Berlin, the gallant pilots of the airlift and his inner circle of supporters, as well as his wife and four small children, ‘who took the daily insults, threats and privations of the Communist rats [and] who walked like bears.’

Never shy to blast his own trumpet, he also praised himself. He had been the first to recognise that Berlin faced a grave danger from the Soviets and he had also been quick to realize that you need to punch hard and low if you intend to win.

When summing up his four years in Berlin, he was characteristically frank. ‘Only a fool would say that I had not done a good job.’ As so often with Howley, the statement was cocky, brash and outrageous. But it was also true.

Giles Milton is the internationally bestselling author of eleven works of narrative history, including Soldier, Sailor, Frogman, Spy: How the Allies Won on D-Day. His previous work, Churchill’s Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare, is currently being developed into a major TV series. Milton’s works—published in twenty-five languages—include Nathaniel’s Nutmeg, serialized by the BBC. He lives in London and Burgundy.