by Alan B. Trabue

Writing my memoir, A Life of Lies and Spies: Tales of a CIA Covert Ops Polygraph Interrogator, caused me to reflect on the scope of changes to the polygraph program I encountered during my forty-year CIA career. Starting as a journeyman examiner and later assigned overseas as a covert ops examiner, I eventually became a senior manager. I directed the applicant, industrial, re-investigation, and operational programs. In addition, I was Director of the CIA Polygraph School for six years and an adjunct instructor at another polygraph school for eight years. The breadth of my experience in polygraphy shaped a unique perspective, as I was intimately involved in all aspects of the profession for four decades.

Each decade brought an increase in testing and a corresponding increase in the size of the examiner workforce. When I entered the program in 1972, polygraph was a relatively small unit with almost one-third of its positions located at overseas offices in support of the Directorate of Operations’ efforts to validate recruited spies. Today, the office, with four times as many examiners and few positions overseas, has had to move twice over the years in order to accommodate its increased size.

During my early years in the polygraph program, the examiner cadre was composed of seasoned operations and security officers, some with decades of experience. The cadre is significantly younger now. A dramatic increase in the number of two-income families increasingly impacted the office over the years. Recruitment was hurt because many candidates were unwilling to attend a three-month basic polygraph examiner training course run out of state. Family and financial concerns also dissuaded officers from accepting domestic and overseas assignments and, in part, led to the closing of four domestic field offices due to lack of interested candidates.

In 1972, the state-of-the-art polygraph simply monitored respiration, sweat gland, and cardiac activity. Instruments then became electronically enhanced and added a second pneumograph. In later years, a sensor to monitor subject movement was added. Finally, when the digital age hit, the polygraph instrument was computerized, becoming a networked operation with digital recording, data storage, and remote monitoring by supervisors. Computerization brought the most work-altering changes during my career.

My initial polygraph training was conducted by the office’s training officer. In later years, the influx of greater numbers of students required sending them to a commercial polygraph training institution. For over a decade, the polygraph program had new recruits trained in the CIA Polygraph School, an American Polygraph Association accredited training institution. I taught thirteen classes of the CIA Polygraph School in polygraph and interrogation. It was an extremely rewarding assignment and a high point of my career. The skills the students developed served them remarkably well throughout the rest of their CIA careers as they rose in grade and title. Working as an adjunct instructor, I trained twenty-four classes at the current school used by the CIA.

In 1972, the CIA polygraph program utilized its own test procedures and applied its own test formats to cases it conducted. Over the decades, the office became increasingly less isolationist and sought standardization with the rest of the Intelligence Community. It now follows the established, standardized methodologies specified in the Federal Psycho-physiological Deception Detection Examiner Handbook.

Significant changes to polygraph test coverage were made over the years. Forty years ago, any illegal drug use by an applicant as an adult would have disqualified him from CIA employment. With increasing drug availability and a corresponding increase in experimentation, the scope of the drug question changed from any adult use to any recent use. When I first started in the office, a test question that dealt with adult homosexual activities as a possible blackmail concern became a non-issue, and testing for it ceased a long time ago. The growth of terrorism necessitated screening for support of terrorist activities. Also, computerization and its access to the intelligence network necessitated screening for deliberate compromise or sabotage of our computer systems.

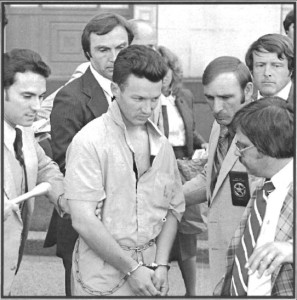

Applicant and operational testing comprised most of the office’s work done in the 1970’s. But, changing times brought new security concerns. Americans were caught spying against their own country, including Christopher Boyce and Daulton Lee, William Kampiles, Aldrich Ames, Robert Hanssen, Harold James Nicholson, and John Walker. In the 1980’s, known as the Decade of the Spy, sixty Americans attempted or actually committed espionage against the United States. Increasingly vigilant, the CIA ramped up re-investigations of CIA employees and industrial contractors, adding greatly to the case load of CIA polygraphers.

Change was undeniably beneficial to the quality of the program, though, at times, difficult to manage. As a senior officer, I oversaw changes in staffing, facilities, instrumentation, computerization, testing methodology, and training. My uncommon longevity and broad experience in the CIA polygraph program provided a unique perspective while these changes came together to make it what it is today, the world’s preeminent polygraph program.

A second generation CIA officer, Alan B. Trabue spent his youth in Uruguay, Japan, and Saipan. He traveled extensively in Central America, South America, the Far East, Southeast Asia and Europe interrogating foreign spies. For five years, he directed the CIA’s world-wide covert ops polygraph program. He served as Director of the CIA Polygraph School for six years and as an adjunct instructor at the current federal polygraph school for eight years. He is also the author of A Life of Lies and Spies: Tales of a CIA Covert Ops Polygraph Interrogator

“For a cumulative record of service which reflected exceptional achievements that substantially contributed to the mission of the Agency,” Mr. Trabue received the Career Intelligence Medal.