by Tom Clavin

On November 1, 2022, the next Bob Drury and Tom Clavin collaboration, The Last Hill: The Epic Story of a Ranger Battalion and the Battle That Defined WW II hits shelves everywhere. Our last book, Blood and Treasure, was a New York Times and national bestseller, and we have hopes The Last Hill will be too. The week of its publication, I will be on a cross-country book tour and won’t be able to do a column, so I am devoting this week’s column to an excerpt from the new book.

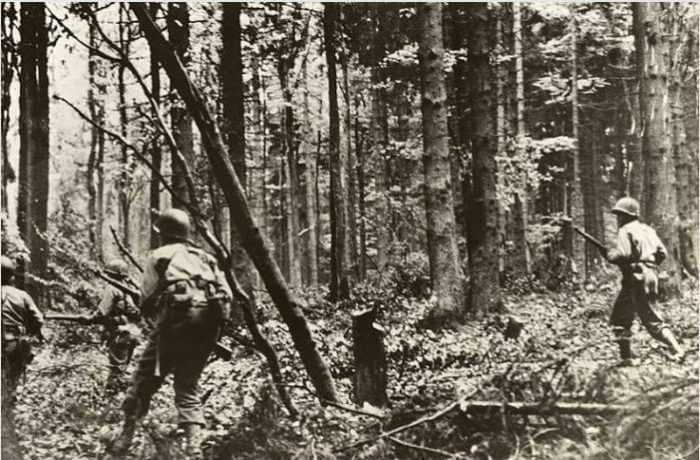

Photo Credit: US Army Signal Corps

The title refers to Hill 400, which is just inside Germany. The day is December 7, 1944, and to penetrate any deeper into the Fatherland the hill must be taken from the elite German forces who occupy it. Thus far, entire regiments have tried and failed. General Eisenhower and his commanders have called in the battle-scarred 2nd Ranger Battalion. As the wintry sun rises that morning, the men of Dog and Fox Companies are poised at the edge of the field leading to the base of the hill, waiting out dueling artillery bombardments until they can attack.

The shelling of the heights began at nearly the same time the two Ranger companies had fanned out along the road. With Lt. Howard Kettelhut relaying coordinates, the eighteen American artillery batteries unleashed a rolling barrage, starting at the base of the hill and marching the detonations up the slope by quadrants. At the same time, German mortarmen began dropping shells several hundred yards to Dog and Fox Companies’ rear. The assault force was caught in the middle, and every Ranger recognized that it was only a matter of time before the enemy guns would re-establish their range projections and “walk their arty” straight into their midst.

With nowhere to go but forward, word was passed down the line to fix bayonets. Big Stoop Masny, on the left flank, dispatched runners to remind his Fox Company Rangers that the moment the American artillery ceased, every trooper was to empty one full clip from his weapon into the base and slope of the hill before the mass charge—a marching fire assault, in military terminology. Morton McBride on the right did the same with Dog. If the horizontal hail of bullets could keep the Germans buried in their hidden bunkers, it might buy a few extra seconds to cross the icy clearing.

American shellfire was still erupting on Hill 400 when Fox Company’s Lieutenant Thomas Rowland tapped the shoulder of the platoon sergeant L-Rod Petty. Like Lt. McClure, Rowland was new to the outfit, a replacement only arrived in the last few weeks. The Germans in the bunkers at the base and on the facing slope of the hill had yet to show their hand. Not knowing the enemy positions made Rowland uncomfortable. “Send out a scout,” he told L-Rod Petty.

The platoon sergeant looked at Rowland as if he had two heads. And waste a man? He shook his head, no.

Rowland repeated the order. Petty growled. “Fuck you, no way.”

Angry and flustered, Rowland turned to the company staff sergeant Bill McHugh. Before the officer could speak, McHugh shook his head. “No, sir.”McHugh had hugged L-Rod Petty’s ass since the two had captured the enemy machine gun back atop Pointe du Hoc. He trusted the toothless BAR man’s instincts a hell of a lot more than he did this newbie second lieutenant.

Rowland finally found a Ranger to obey his command. PFC Gerald Bouchard humped over the road’s embankment and made it two or three steps before a single bullet pierced his belly. An enraged Petty and McHugh dragged the wounded private back to cover by his heels. Petty was still dosing Bouchard’s gutshot with sulfa powder when, at precisely 0730, the American barrage ceased. Behind the Ranger line, German artillery detonations had crept to within thirty yards. Masny and McBride shouted near simultaneously, “Go!”

It was as if a tense and furious serpent had finally uncoiled and struck. The Rangers, firing at will, leapt from their defilade and surged across the open field. Bill McHugh, still seething over what he considered the new lieutenant’s ineptitude, emptied the clip of his tommy gun. “Let’s go get the bastards!” he hollered at the top of his lungs.

He was answered by what Lt. Len Lomell described as a wild chorus of “Indian war whoops.” Enemy machine gunners and riflemen secreted on the slope finally opened up. Rangers dropped left and right. Not far from Lomell, PFC Kenneth Harsch had taken but a few steps when a mortar round “splattered” his face. Another trooper, new to the outfit, took one look at the raw meat that sprouted from Harsch’s pole-axed neck and froze, dropping to the ground and curling up into a ball. Lomell did not begrudge him; combat, he had learned, turned men into mysterious animals.

Turning to wave his men on, Lt. McBride took a slug in his right buttocks. Bleeding and cursing—he considered it an insult to have been shot in the ass—he dropped to one knee and continued to urge his Dog Company Rangers forward. When the last man had passed him, he hobbled back toward Doc Block’s aid station. He stopped often along the way to treat and mark the location of injured men. Among them was Fox Company’s Bill McHugh. The “bastards” had got him before he could get them.

At the edge of the field where it met the road, McBride spotted the wounded Ranger Tony Ruggiero, the tap dancer from Massachusetts who had been with the outfit since Camp Forrest. A large piece of shrapnel had sliced through one of his legs. McBride remembered “Rugg” entertaining his platoon—and likely concealing his own anxiety—by dancing to the strums of a smuggled ukulele during the Channel crossing back on June 6. Ruggiero, who was all of five-foot-three, was lucky if he tipped the scales at one-hundred-and-twenty pounds. Despite his wound, McBride bent down and threw him over his shoulder. Ruggiero puked all over his company commander’s back.

It took less than two minutes for what was left of the assault force, a little over one-hundred Rangers, to reach the base of the hill. The surrounding trees shook as scores of fragmentation grenades turned log bunkers into kindling. The Germans dug in on the slopes turned and ran for the top. The shrieking Rangers followed, the frozen scree beneath their combat boots giving way as they scrambled up the forty-five-degree incline. The adjusted German mortar barrage nipped at their heels as they climbed. It was like scrabbling up a thirteen-hundred-foot child’s playground slide while being shot at.

Watching the assault from the church bell tower, Howard Kettelhut called in a withering round of artillery. American shells—105mms, 155mms, 240mms, eight-inch howitzers—raked the top of the hill. The ground shook from the force of the explosions. Kettlehut halted the barrage as the first wave of Rangers neared the crest. The fight atop Hill 400 was now a chaotic brawl. Americans and Germans, many with no opportunity to reload, attacked each other with knives, entrenching tools, steel helmets, bare fists. “No quarter was asked,” notes the Army veteran-turned-military historian Douglas Nash, “and none given.”

Originally published on Tom Clavin’s The Overlook.

Tom Clavin is a #1 New York Times bestselling author and has worked as a newspaper editor, magazine writer, TV and radio commentator, and a reporter for The New York Times. He has received awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, and National Newspaper Association. His books include the bestselling Frontier Lawmen trilogy—Wild Bill, Dodge City, and Tombstone—and Blood and Treasure with Bob Drury. He lives in Sag Harbor, NY.