by Mitchell Stephens

During the First World War Lowell Thomas was confirming—as he zipped to Europe, through Europe and then to the Middle East— that being in motion was his preferred state. And the direction he preferred for all this moving about, the direction that might best satisfy his adventure addiction, was also becoming clear: toward the increasingly exotic. From Egypt Lowell had made it to Palestine.

And now he was hearing talk of a significant military campaign under way in Arabia—at the time, for a European or American, among the most exotic locales on Earth. Lowell had even spoken with a colorful Englishman, in the habit of dressing in Arab robes, reputed to be riding at the head of the Arab forces.

Arabs were among the ethnic groups using the First World War as occasion to try to gain independence from the sprawling, heterogeneous and increasingly rickety Ottoman Empire and Turkish rule. Since that empire was allied with Germany in this war, and with an eye toward postwar influence in the region, the British were enthusiastically encouraging this “Arab Revolt”—supporting it, advising it, funding it.

They were primarily working with the Hashemites, Sherif Hussein bin Ali and his sons, who had dynastic claims in the western part of the Arabian Peninsula, the Hejaz. Major T. E. Lawrence first tagged along with an emissary to the Hashemites, then became an emissary himself.

Thomas Edward Lawrence was born on August 16, 1888, in Wales to a couple hiding what at the time was a scandalous secret: they were not married to each other. T. E. Lawrence’s father, Thomas Chapman, was an Irish-English gentleman and a baronet who had inherited an estate in Ireland. Chapman left that estate, Ireland, his wife and two daughters and ran off with his children’s strong-willed governess.

Her first name was Sarah. There is some dispute about her last name, for T. E. Lawrence’s mother, too, appears to have been illegitimate. Chapman’s wife would not grant him a divorce. Nonetheless, after they ran off, Thomas and Sarah pretended to be married and adopted the last name Lawrence. Despite or maybe because of the fact that they were “living in sin,” they were quite religious. Thomas was the second of the couple’s five sons.

The family moved to Oxford in 1896, in part because of the educational opportunities it offered the boys. T. E. was generally conceded to be the leader of the five brothers, and he took full advantage of those educational opportunities. T. E. Lawrence won a partial scholarship to Jesus College at Oxford and graduated with first-class honors in modern history in 1910. His specialty was the architecture of the Crusades.

T. E. Lawrence had made his first trip to the Middle East before he graduated from Oxford, traveling through what are now Lebanon and Israel alone, mostly on foot, and sleeping wherever someone would offer a bed or a piece of ground. He was often hungry. He caught malaria. He was robbed and beaten. He seems to have had a marvelous time.

T.E. Lawrence was not religious; nevertheless, he had a strong ascetic streak—a penchant for self-denial, even martyrdom. It served him well on that first trip to the Middle East, as it would later serve him well with Arab fighters in the desert. T. E. Lawrence immersed himself in Arabic and developed a love for the Arabian people and their culture, which his misfortunes and adventures only seemed to strengthen. “I will have such difficulty becoming English again,” T. E. Lawrence writes in a letter to his mother.

Indeed, he managed to spend most of the years from his graduation to the outbreak of the First World War helping supervise an archaeological dig at Carchemish—near the Euphrates—then part of the Ottoman Empire, now near the border between Turkey and Syria. He began wearing Arab dress. It may have been the happiest period of T. E. Lawrence’s life. “The foreigners come out here always to teach, whereas they had much better to learn,” T. E. Lawrence writes his family.

After the First World War began, T. E. Lawrence entered the British Army as a second lieutenant, working on maps of the Middle East. His knowledge of Arabic and of the area won him a position in military intelligence and a quick transfer to Cairo. T. E. Lawrence—a scruffy officer, never particularly respectful of military hierarchies or procedures—began encouraging his superiors to support Arab forces in their own nationalistic rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. And he began lobbying to get closer to that rebellion.

T. E. Lawrence applied for transfer within the British military to the Arab Bureau. On October 16, 1916, he landed for the first time on the Arabian Peninsula. Within a week he had been introduced to Sherif Hussein’s three eldest surviving sons and was particularly impressed with one of them, Sherif—the title translates as “prince” or “ruler”—Feisal. They began talking strategy.

That initial mention of Major (he had been promoted) T. E. Lawrence in one of Thomas’ notebooks was an account of the effort a month earlier by Lawrence and some Arab forces to hold on to the town of Tafilah, just south of the Dead Sea, which the Arabs had captured and the “Turks” were trying to retake. Here it is in its entirety:

Maj. T. E. Lawrence

At southern end of Dead Sea, he & six Bedouins ran into outposts of a whole Turk Division, only had one machine gun & he was manning that. Held Turks off until he could send for re-enforcements. Said: “I believe I ran, yes, I’m sure I ran. But I kept count of the number of paces I ran so we had the range.”

When his re-enforcements arrived he left part of his men where they were & took most of his force around behind Turk Div. Killed divisional commander, took 500 prisoners & killed all the rest.

In his shows and writings, Lowell Thomas would go on to, as Ben Hecht later put it, “half invent the British hero, Lawrence of Arabia.” And this is Thomas’ initial sketch of that supposedly fearless, shrewd, indomitable leader of Arabs and slaughterer of Turks. It is, therefore, a significant piece of evidence.

In his shows and writings, Lowell Thomas would go on to, as Ben Hecht later put it, “half invent the British hero, Lawrence of Arabia.” And this is Thomas’ initial sketch of that supposedly fearless, shrewd, indomitable leader of Arabs and slaughterer of Turks. It is, therefore, a significant piece of evidence.

Lowell Thomas seems to be either taking notes in these initial paragraphs on “Maj. T. E. Lawrence” or writing from notes, and given the appearance of the first person in them, they appear to be notes from an interview with T. E. Lawrence himself.

In that case the story of T. E. Lawrence’s holding off a whole Turkish division at Tafilah by firing a machine gun came from Lawrence. And that story is almost surely untrue. It does not appear again—even in the most hagiographic biographies of T. E. Lawrence, even in the one Thomas himself would write.

A few pages later in this notebook, Thomas returns to the subject of “Maj. T. E. Lawrence.” Here Thomas records a full seven pages of notes. He jots down his first description of Lawrence: “5 feet 2 inches tall. Blonde, blue sparkling eyes, fair skin—too fair even to bronze after 7 years in the Arabian desert. Barefooted, costume of Meccan Sherif.” We know that at this time T. E. Lawrence, in full Arab dress, posed for photographs by Harry Chase. And these extended notes by Thomas include discussions of T. E. Lawrence’s adventures that must have been based on interviews in Jerusalem with Lawrence.

The dozens of biographers of T. E. Lawrence disagree on the extent of Lawrence’s own responsibility for inflating his accomplishments and thereby helping create the legend of “Lawrence of Arabia.” But it is apparent even from Thomas’ initial efforts to record T. E. Lawrence’s story—which would also have been Lawrence’s initial brush with attention outside the military—that T. E. Lawrence inflated some of his accomplishments and therefore contributed quite a bit to that legend. There is other such evidence. If “Lawrence of Arabia” was half invented, Lowell Thomas must share credit for the invention with T. E. Lawrence himself along with some of his votaries in the British military.

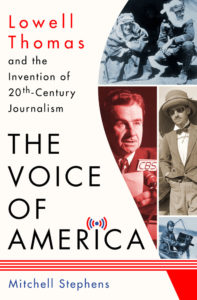

MITCHELL STEPHENS, a professor of journalism in the Carter Institute at New York University, is the author of A History of News, a New York Times “notable book of the year.” Stephens also has written several other books on journalism and media, including Beyond News: The Future of Journalism and the rise of the image the fall of the word. He also published Imagine There’s No Heaven: How Atheism Helped Create the Modern World. Stephens was a fellow at the Shorenstein Center at Harvard’s Kennedy School. He shares Lowell Thomas’ love of travel and had the privilege of following Thomas’ tracks through Colorado, Alaska, the Yukon, Europe, Arabia, Sikkim and Tibet.