By Callie Oettinger

They thought we were heroes, but most of us that were the Raiders, pulled our one-year tour in Vietnam and then came home. These POWs were there 5-to-7 years. They carried on the battle. They did not give up. When you compare that to what was going on at home—protests, people going to Canada to avoid military service—while the POWS were rotting and suffering and being tortured against the laws of warfare, they were the heroes, not us.

—John Gargus, Son Tay Raid radar navigator, MC-130E “Cherry Two”, author of The Son Tay Raid: American POWs in Vietnam Were Not Forgotten

November 21, 1970: The POWs heard the helicopters, missiles and high flyers. There hadn’t been any bombings north of the 19th parallel since President Johnson ordered the halt—and even before that, they’d taken place during the day.

The Raiders, made up of a select team of Green Berets and U.S. Air Force Special Operations forces, were on their way to rescue POWs at Son Tay prison. They had 30 minutes to get in and out. Intel had indicated there were about 60-70 POWs. Different portions of the rescue had been practiced 170 times—including every imaginable contingency plan. The one scenario they hadn’t planned for hit everyone involved as Bud Sydnor called “Rollback,” without a single POW found and/or returning home with them.

“The shocking and bold plan to rescue American prisoners of war from North Vietnam required a unique, specially trained joint military task force and approval from the president of the United States, Richard M. Nixon,” wrote John Gargus, the radar navigator on the MC-130E “Cherry Two,” in his book The Son Tay Raid: American POWs in Vietnam Were Not Forgotten. (Read “Son Tay Raid: Feasibility Study,” excerpted from The Son Tay Raid)

“Military leaders assembled the best available Army and Air Force volunteers in Florida for training in utmost secrecy, half a world away from those who suffered deprivation, brainwashing, and torture in enemy captivity. The prisoner of war camp selected for this rescue was near Son Tay, twenty-three miles west of North Vietnam’s capital of Hanoi. It was in the most heavily defended area of the country, close to MIG interceptor air bases, and carefully positioned antiaircraft artillery and surface-to-air missile sites. The raid planners had information that this camp held about sixty Air Force and Navy airmen who had survived being shot down on missions over the enemy’s territory.”

Though different elements of rescue missions had been executed in the past, this operation required pioneering planning, extensive training, and innovations in equipment.

In the “Commander’s Comments” section of his after-action report, Brig. Gen. Leroy J. Manor, wrote:

“Each man knew precisely what his task was under each contingency and was an expert in his area—from demolition specialist to the radio operator. The rapid and smooth transition to an alternate plan at the objective testifies to ability of the force to adapt to varying condition. Innovations were made in equipment, procedures, and tactics. The capability was developed to enter cell block regardless of degree of security or hardness of construction. Night viewing devices were obtained to provide maximum visibility for the road block elements. A night firing optic was obtained from commercial sources which was adapted to the weapons and increases night firing effectiveness threefold. The communications gear and procedures were specially adapted to provide defendable command and control on the ground. Redundancy in communications was considered essential and provided. The extensive joint training with the helicopter and A-1 elements assured a closely knit team which was essential to survival and extremely effective.” (Read: Brig. Gen. Manor’s full report and other declassified documents.)

“The overall plan was conceived in the Pentagon and that’s where they determined we’d need forces inside the compound, forces to protect the immediate vicinity, and forces to destroy the bridge and provide for perimeter defense,” said Gargus.

Then there was the question: How do they get there? And: How do they get there undetected?

“Navigation in those days was so poor,” said Gargus. “The helicopters needed C-130s to take them in and so did the skyraiders that would provide air-to-ground support. And then the Ground and Air Forces had to work together. We needed split-second timing. All assault participants were expected to execute their assigned tasks before the opposing forces could organize their defenses. That meant we needed a high-altitude diversion to focus the enemy’s attention away from what we intended to do on the ground.

“We needed a naval diversion east of Hanoi to conceal our entry into North Vietnam from the west. Early warning radars would be scanning to the east, while we approached from the west. Then we would create a Mig trap scenario that would cause the enemy to opt for surface to air missile (SAM) defense instead of Mig interceptors that could make mince-meat out of our low flying helicopters and skyraider A-1 aircraft. This was done by a timely approach of our high flying Mig killing F-4s from Laos. They would establish orbits over the Phuc Yen Air Base where Migs were on night alert. This worked perfectly. Alerted Migs never took off and a high altitude SAM battle ensued. For this we brought in 5 F105 Wild Weasel SAM suppressors that protected the orbiting—flight bait- F-4s.” (Read “Son Tay Raid: Mig Trap Scenario and SAM Concerns,” excerpted from The Son Tay Raid)

Then there was the training.

The Ground Forces involved in the Son Tay mission had 30 minutes to get in and out. Joint forces trained at Eglin AFB to reach that target mission requirement. (Read “Son Tay Raid: Ground Assault Planning,” excerpted from The Son Tay Raid)

“Eglin range is home for all types of weapons testing,” said Gargus.” The alibi was that we were testing—testing at a test range for a classified project. We weren’t really bothered.”

The CIA constructed “Barbara”—a scale model of the Son Tay Prison camp—and a life-sized model was created out of cloth wrapped around 2 x 4’s staked into the ground.

“Someone suggested taking down the compound every time a Russian satellite went over it,” said Gargus. “We flew our own high altitude recon and took photos. There was too much apparent traffic in the area—too many random direction vehicular tracks—for any other photo interpreter to equate that compound with the anything else.”

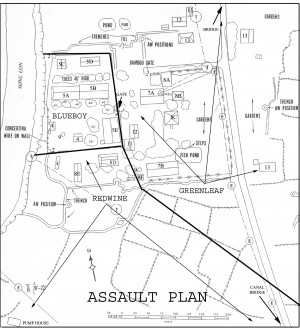

Training records show that we executed 170 practices of various phases of the raid. “Most of the practice sessions were conducted separately with only one group (Blueboy, Redwine, or Greenleaf) or element of a group alone in the area,” said Gargus. “This had to be done when they used live ammunition. Cloth walls would not stop bullets or grenade fragments from injuring others behind such make-shift walls. Full rehearsal with all participants in the area in real time had to be conducted with simulated fire. Also, there were sessions that involved helicopter landings with troops, marshaling of freed POWs in the landing zone, as well as ground to air communications and tactics involving A-1E skyraiders in close air support.”

Training took place around the clock, with joint training at night. The cliché inter-service rivalries didn’t exist there as everyone worked together.

Working together meant brainstorming innovations—from resizing the size of the non-standard ammunition magazine pockets on the standard-issue vests to running down equipment at the local hardware stores.

They knew from some of the prisoners who had been released that the prisoners at Son Tay might be chained to their beds and/or floor, around their ankles. “We knew what was needed to free them,” said Gargus. “We had to have saws, bolt-cutters, and other equipment, so we ran to ACE hardware stores and other local suppliers and got what was needed.”

Throughout all of this training, the majority of those involved lacked the key details about the mission.

November 20th the mission’s target and location were announced in the briefing following the confirmation of the launch order.

“Col. ‘Bull’ Simons gave them an opportunity to opt out and no one opted out,” said Gargus. “It was a shocker—and there was tremendous enthusiasm, knowing that we could do this in 30 minutes and be out of there. We were so enthusiastic and things were going fine.”

As the Raiders prepared, three strike carriers were readied for the Navy’s diversion mission. They were tasked with diverting the enemy’s attention, so they wouldn’t focus on the Son Tay region.

“Going into North Vietnam signals from enemy radars were being monitored by our Electronic Warfare Officer, said Gargus. “The radar wasn’t picking up the Raiders so we knew that the diversion the Navy was creating was working—everything seemed perfect. We knew we were sneaking in successfully.”

During the planning stage, there was a note about a facility south of Son Tay prison. It resembled the target location, but there wasn’t a question about the forces mistaking it for the target prison.

In his report, BG Manor wrote:

“The ground force of 56 US officers and men was transported on three helicopters. The Assault Group (Blueboy) was transported by HH-3; the Command Group (Redwine) including the Ground Force Commander (Wildroot) and the Support Group (Greenleaf) plus the Alternate Ground Force Commander, by HH-53. The approach was made on an area similar in appearance to the target but approximately 400 meters south of the target area. The pilots of the HH-3 and the third HH-53 recognized the approach error and recovered sufficiently to enter the target area as planned with minimum delay. The pilot of the first HH-53, not realizing the approach error, inserted and debarked the Support Group south of the target area. The pilot of the second HH-53 did a 360 degree turn to realign his approach with that of the HH-3. Recognizing that the first-HH-53 was absent from the planned formation, the pilot of the second HH-53 executed his portion of Plan Green by directing his left mini-gun to fire on guard building 7B while he landed. The Ground Force Commander was advised that the first HH-53 had not landed at the target area at H+2-1/2 minutes.”

Within the first 17 minutes of the mission:

- the Support Group landed at the wrong compound, to the south of the target, took—and engaged—fire there, and was extracted and then debarked at the target location;

- the Command Group came under fire, and engaged NVA operators in return;

- the Assault Group experienced a violent landing, when the HH-3’s blades sliced through a tree trunk and limbs;

- Security Elements 1 and 2 were engaged-and then suppressed- fire;

- Security Element 3 was engaged in fire, but disengaged as Command Group gave the word to pull back;

- Action Elements 1, 2, and 3 had completed operations in their areas of responsibility (which included releasing POWs) and transmitted that there were “Zero items;”

- and the Support Group had secured the LZ for extraction.

At about the 33-minute mark, after everyone had been extracted, a fire erupted, believed to be from the demolition charge earmarked for the left-behind HH-3.

And then there were the air and support operations, which included:

- the mission of playing “bait” to keep the enemy’s eyes off the Task Group;

- the Navy operations, which launched 59 Navy aircrafts for sake of diversion;

- and the search-and-rescue mission for the ejected crew of the F-105G that took fire and burned out during the air operations.

“I did not really believe that there was not anyone there until we were back on the ground,” said Gargus. “I was in the plane monitoring the pick-up of the two members who ejected, so as a navigator I was busy until we landed. I didn’t have time to dwell on anything else until after we landed and the reality hit me. We were so dejected.”

“We did everything according to our well rehearsed plans and came home unscathed,” said Gargus. “The only thing missing was the prisoners. We did the job as well as we could have. We couldn’t blame ourselves. We did everything possible. But . . . How history could have changed had we brought them home. What an impact that could have had on the Paris peace talks.

For Gargus and others involved in the mission, the POWs were top-of-mind.

“My biggest concern was that there would be severe punishment for the remaining POWs—beatings and tortures and killings. Were afraid of knee-jerk reactions and feared that these cruel guards would kill off some of the prisoners before the responsible authorities intervened.”

Though they didn’t return home with the POWs, the Raiders found out later that the NVA improved its treatment of the POWs.

Right after the raid, the POWs were herded into down-town Hanoi. “The guards were frightened,” said Gargus. “Some admitted to the POWs that there was a rescue attempt. They decided not to take reprisals and the treatment was improved as well. You had people who were for years in isolation who could not speak to other Americans. The only way they could communicate was to tap on the walls. All of a sudden these people in isolation ended up in the Hanoi Hilton in a small room together with as many as 40 other captives. And then the ones in poor health were cared for by others and the food improved.”

Why were the POW’s near Hanoi instead of Son Tay?

It’s been said that the flooding was the reason, but the reality, which Gargus found upon the release of Vietnamese documents years later was a routine review of the camps. “In early 1970, the command element ordered a review of all of the prison camps—which ones were vulnerable to rescue—and came to same conclusion that we did—Son Tay was the most vulnerable. “

As news about the raid was released, it received a mixed reaction.

Though most agreed the men involved in the raid were to be praised for their actions and courage, the decision to proceed with the raid, and the intelligence upon which the raid was based, was questioned. Though the planners had impressive intelligence—such as locations of SAM sites—which allowed the teams to enter North Vietnam without detection, the intelligence about the location of the POWs was the main focus.

During hearings before the Committee on Foreign Relations, Secretary Melvin R. Laird was questioned at length about the intelligence, pulled from the official record (Read the full record: “Bombing Operations and the Prisoner-of-War Rescue Mission in North Vietnam”):

Senator Gore: Mr. Secretary, what I am trying to get at, if you will assist me, is some explanation of the error in intelligence. This is a grave and a dangerous mission, executed with valor and bravery on the part of our soldiers at great risk to themselves. Surely it should not have been undertaken unless intelligence indicated clearly that prisoners were there. Whether it should have been done then is another question.

Secretary Laird: I would be pleased to have an opportunity to discuss that because I believe that as far as the operation is concerned, the intelligence was the best we possibly could have had.

First, we looked over all of the suspected POW camps; these are suspected camps because the North Vietnamese are in violation of the Geneva Convention, which requires all POW camps be designated. The POW camps in North Vietnam are not designated in accordance with the Geneva Convention.

But we know of certain suspected area where camps could possibly be located. We have, of course, photographic means of identifying these areas.

We looked over all of the suspected POW areas, and we found that of all of the area in North Vietnam, this was the only camp in which there were areas surrounding the camp that made it possible for us to make a landing with our special mission ground forces outside the site.

It also gave us the opportunity to make a landing with the initial assault force inside the camp itself.

Senator Gore: Mr. Secretary, this is very——

Secretary Laird: Now, the difficulty, as far as our intelligence is concerned, was that there is no camera that has ever been constructed that can see through the roofs of these buildings. Our intelligence was accurate as to the location of every building, but we could not see inside each building. The men landed; they had their assignments; they carried them through; they broke the locks on the cells; they went in and searched every cell; they went through this area; the towers where to guards were to be located, everything was exactly as they had been told.

Senator Gore: Except the prisoners were not there.

Secretary Laird: The windows in the radar that our intelligence had given us, which showed us how to get through what we call the Red River Valley with these helicopters and with these landing forces, was excellent.

There was no detection of these forces until 1 minute before the landing. The intelligence on where troops were located in the area was excellent. The intelligence on SAM sites, the intelligence on anti-aircraft positions, every bit of intelligence proved to be correct.

The only intelligence that we did not have was the pictures inside the cells and this was something that every man on the mission knew too. This was something that I personally discussed with them and discussed with our intelligence people who were working on this mission.

Senator Gore, I felt the risk was worth it, and I recommended this mission, and I take the responsibility. But I cannot fault the intelligence that was supplied to us. We do not have men on the ground in North Vietnam and I hope that we can develop a camera some day that will actually see into the cells of suspected POW camps, but we do not have that equipment in our inventory at the present time.

* * *

Senator Church: Mr. Secretary, you have said there is not camera that will shoot through the top of buildings. Yet, we have been undertaking aerial reconnaissance flights over North Vietnam, no doubt, we have been taking aerial photographs of the courtyard. Don’t you have evidence to suggest that the American prisoners of war were there before you ordered the rescue mission? What kind of evidence did you have which suggested they were there to justify the risk of the mission?

Secretary Laird: We had the evidence of construction, as I think you can see by this picture of the model of the compound which was used in our training exercise.

Senator Church: Did you have aerial photographs that showed our prisoners of war outside on the grounds at any time?

Secretary Laird: No, that is not something that we look for in a POW camp, Senator Church, because when we talked to some of the returning POW’s we found that exercise was something that was given to them as a real treat and sometimes it was only for holidays.

Senator Church: You had no such photographs, then, of any prisoners there?

Secretary Laird: No such photographs were available.

Senator Church: Did you have other intelligence information suggesting that the prisoners were there?

Secretary Laird: We had very good intelligence information that this suspected POW camp, in fact, had prisoners in it. That is all I care to say.

Lessons Learned

In the “UH-1H Training” section of his after-action report, Manor wrote about the difficulty of “mating the UH-1 and C-130 in formation flight at maximum performance of both aircraft.” And then he made a point that could be applied to all portions of the planning and training:

“With no precedent in Army experience and no documentation which would serve as a guide, progress was made in small, controlled increments in what was substantially a test program. This program would have proceeded with greater confidence, though at a less vigorous pace, in a test environment. Developing this high level of proficiency in both a primary and reserve crew was also a source of growth . . .”

Though the Raiders didn’t bring home the POWs—and though some questioned the decision to execute the operation—history has proven the planning, training and execution of the raid to be a model for operations to follow.

While it is impossible to apply the plans and training of one operation as an overlay for another, the lessons can be transferred.

“The value of extensive and detailed rehearsals in the event of emergencies or changes in plans cannot be overemphasized . . .” wrote Manor. “Fundamental to this were the command arrangements that allowed the Task Group the freedom to develop optimized concepts for the situation at hand and, once approved by the National Command Authority, vested in COMJCTC go-no go authority and operational control over all forces with authority to take all tactical decisions from launch to recovery of the force. This degree of command prerogative is considered essential for operations of this type.”

Those “optimized concepts” are the roots of operations and equipment innovations seen today.

“Now we have special teams in all of our services that can execute a raid in a few days,” said Gargus.

“We have drones now that can monitor the progress of a raid. We had six people designated to be radio operators with heavy and cumbersome back-pack radios—now everything is miniaturized in the headset, inside of the soldier’s helmet. Every element on the ground had to have a forward air guide—who had to be trained to call airstrikes. With small number of pilots and aircraft, the air guides, learned the voices of everyone on their frequency. Now we have Air Force combat air controllers that are imbedded with the troops on the ground.

The Raiders and POWs Today

Years after the raid, Ross Perot played a key role in bringing the Raiders and the POWs believed to be Son Tay together for the first time. Though Gargus wasn’t at the first reunion, he was there for the one in Austin, TX. Since then, they continue to meet every few years.

“It’s still great getting back together after the years. Many of the POWs joined our association (Son Tay Raider Association). They thought we were heroes, but most of us that were the Raiders, pulled our one-year tour in Vietnam and then came home. These POWs were there 5-to-7 years. They carried on the battle. They did not give up. When you compare that to what was going on at home—protests, people going to Canada to avoid military service—while the POWS were rotting and suffering and being tortured against the laws of warfare, they were the heroes, not us.

Excerpted from The Son Tay Raid: American POWs in Vietnam Were Not Forgotten by John Gargus.

Copyright © 2010 by John Gargus.

Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Texas A&M University Press.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited.

Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the publisher.

CALLIE OETTINGER was Command Posts’ first managing editor. Her interest in military history, policy and fiction took root when she was a kid, traveling and living the life of an Army Brat, and continues today.