WCAG Heading

WCAG Heading

WCAG Heading

By Gavin Mortimer

The ‘fossilised shits’ were soon making life hard for [David] Stirling as he sought to recruit soldiers for his new unit. ‘It was essential for me to get the right officers and I had a great struggle to get them,’ he recalled, labelling the middle and lower levels of Middle East Headquarters (MEHQ) as ‘unfailingly obstructive and uncooperative … astonishingly tiresome.’(1) The officers he wanted were all members of the recently disbanded Layforcebored and frustrated and desperate for some actionbut MEHQ didn’t want to see them join what they considered a renegade unit, despite the fact it had Auchinleck’s seal of approval. One by one, however, Stirling got his men: lieutenants Peter Thomas and Eoin McGonigal, Bill Fraser, a Scot, Jock Lewes, a Welshman, and Charles Bonington. In his late 20s, Bonington was the oldest of the officers, an Englishman with a taste for adventure who had abandoned his wife and nine-month old son six years earlier and gone to Australia where he worked as a newspaper correspondent. (The son, Charles, would grow up to become one of Britain’s most famous mountaineers.) Bonington was actually half-German, his father being a German merchant seaman who had taken British citizenship as a young man, changed his name from Bonig to Bonington, and then married a Scot. The one officer whose superiors were only too pleased to see join Stirling’s mob was Blair Mayne. Though the 6ft 4in Irishman had distinguished himself with Layforce during the battle for Litani River, a seaborne assault on Vichy French positions in Syria, Mayne had a reputation for hot-headedness away from the battlefield. While in Cyprus in the summer of 1941 he had threatened the owner of a nightclub with his revolver over a dispute about the bar bill, and a month later he had squared up to his commanding officer, Geoffrey Keyes, son of Sir Roger Keyes, Director of Combined Operations, and the sort of upper-class Englishman Mayne despised.

Legend has it that Mayne was in the glasshouse when Stirlingon the recommendation of Colonel Laycockinterviewed him for L Detachment, but in fact the Irishman was idling away his days at the Middle East Commando base while he waited to see if his request for a transfer to the Far East had been accepted. Mayne hoped he would soon be teaching guerrilla warfare to the Chinese Nationalist Army in their fight against Japan, but within minutes of Stirling’s appearance he had pledged his allegiance to an incipient band of desert guerrilla fighters.

With his officers recruited Stirling now set about selecting the 60 men he wanted. Though he picked a handful from his old regiment, the Scots Guard, Stirling plucked most from the disenchanted ranks of Layforce. ‘We were just hanging around in the desert getting fed up,’ recalled Jeff Du Vivier, a Londoner who had worked in the hotel trade before joining the commandos in 1940. ‘Then along came Stirling asking for volunteers. I was hooked on the idea from the beginning, it meant we were going to see some action.’(2)

Another volunteer was Reg Seekings, a hard, obdurate 21-year-old from the Fens who had been a boxer before the war. ‘When I enlisted they wanted me to go in the school of physical training and I said “not bloody likely”, I didn’t join the army just to box, I want to fight with a gun, not my fists.’ Seekings had got his wish with Layforce, though the raid on the Libyan port of Bardia had been shambolic. Nonetheless it had given Seekings a taste for adventure. ‘Stirling wanted airborne troops and I’d always wanted to be a paratrooper,’ he reflected on the reasons why he volunteered. ‘At the interview a chap went in in front of me and Stirling said to him “why do you want to join?” and he said “Oh, I’ll try anything once, sir.” Stirling went mad “Try anything once! It bloody matters if we don’t like you. Bugger off, get out of here.” So I thought I’m not making that bloody mistake. When it was my turn he asked why I wanted to be in airborne and I said I’d seen film of these German paratroopers and always wondered why we didn’t have this in the British Army. Then I told him that I’d put my name for a paratrooper originally but been told I was too heavy. He asked if I played any sport and I told him I was an amateur champion boxer and did a lot of cycling and running. That was it, I was in.’(3)

The youngest recruit was Scots Guardsman Johnny Cooper, who had turned 19 the month before L Detachment came into existence. He stood in awe of Stirling when it was his turn to be interviewed. ‘Because of his height and his quiet self-confidence he could appear quite intimidating but he wasn’t the bawling sort [of] leader,’ said Cooper. ‘He talked to you, not at you, and usually in a very polite fashion. His charisma was overpowering.’(4)

Having selected his men, Stirling revealed to them their new home. Kabrit lay 90 miles east of Cairo on the edge of the Great Bitter Lake. It was an ideal place in which to locate a training camp for a new unit because there was little else to do other than train. There were no bars and brothels, just sand and flies, and a wind that blew in from the lake and invaded every nook and cranny of their new camp. ‘It was a desolate bloody place,’ recalled Reg Seekings. ‘Gerry Ward had a pile of hessian tents and told us to put them up.’

Ward was the Company Quarter Master Sergeant, one of 26 administration staff attached to L Detachment, and it was he who suggested to Seekings and his comrades that if they wanted anything more luxurious in the way of living quarters they might want to visit the neighbouring encampment. ‘This camp was put up for New Zealanders,’ explained Seekings, ‘but instead of coming to the desert they were shoved in at Crete [against the invading Germans] and got wiped out. So all we had to do was drive in and take what we wanted.’

Something else they purloined, according to Seekings, was a large pile of bricks from an Royal Air Force (RAF) base with which they built a canteen, furnished with chairs, tables and a selection of beer and snacks by Kauffman, an artful Londoner who was a better scrounger than he was a soldier. Kauffman was soon RTU’d (returned to his unit) but his canteen lasted longer and was the envy of the officers who had to make do with a tent. Not that there was much time for the men of L Detachment to spend in their canteen in the late summer of 1941, despite the ‘Stirling’s Rest Camp’ sign some wag had planted at the camp’s entrance. They had arrived at Kabrit in the first week of August and had just three months to prepare for their first operation, one which would involve parachuting, a skill most of the men had yet to master.

‘In our training programme the principle on which we worked was entirely different from that of the Commandos,’ remembered Stirling. ‘A Commando unit, having once selected from a batch of volunteers, were committed to those men and had to nurse them up to the required standard. L Detachment, on the other hand, had set a minimum standard to which all ranks had to attain and we had to be most firm in returning to their units those were unable to reach that standard.’(5)

Stirling divided the unit into One and Two Troops, with Lewes in charge of the former and Mayne the latter. ‘The comradeship was marvellous because you all had to depend on one another,’ said Storie, who was in Lewes’s Troop.(6)

Lewes oversaw most of the unit’s early training, teaching them first and foremost that the desert should be respected and not feared. They learned how to navigate using the barest of maps, how to move noiselessly at night, how to survive on minimal amounts of water, and how to use the desert as camouflage. The men came to respect the earnest and ascetic Lewes above all other officers. ‘Jock liked things right, he was a perfectionist,’ recalled Storie. ‘He thought more about things in-depth while Stirling was more carefree… Stirling was the backbone but Lewes was the brains, he got the ideas such as the Lewes Bomb.’

The eponymous Lewes bomb had finally been created after many hours of frustrating and solitary endeavour by the Welshman. What Lewes sought was a bomb light enough to carry on operations but powerful enough to destroy an enemy aircraft on an airfield. Eventually he came up with a 1lb device that Du Vivier described in the diary he kept during the training at Kabrit.

It was plastic explosive and thermitewhich is used in incendiary bombsand we rolled the whole lot together with motor car oil. It was a stodgy lump and then you had a No.27 detonator, an instantaneous fuse and a time pencil. The time pencil looked a bit like a ‘biro’ pen. It was a glass tube with a spring-loaded striker held in place by a strip of copper wire. At the top was a glass phial containing acid which you squeezed gently to break. The acid would then eat through the wire and release the striker. Obviously the thicker the wire the longer the delay before the striker was triggered [the pencils were colour coded according to the length of fuse]. It was all put into a small cotton bag and it proved to be crude, but very effective. The thermite caused a flash that ignited the petrol, not just blowing the wing off but sending the whole plane up.

Lewes also earned the respect of the men because he never asked them to do something that he was not prepared to do himself. ‘Jock Lewes called us a lot of yellow-bellies and threw out challenges,’ said Seekings. ‘We met the challenges and Jock, whatever he wanted done, showed us first, and once he’d shown us we had to do it. He set the standard for the unit, there’s no two ways about that … he used to say that it’s the confident man with a little bit of lady luck sitting on his shoulders that always comes through.’

During the initial training Lewes tested the men’s self-confidence to its limits. They trained for nine or ten hours a day and often, just as the men thought they could crawl into their beds, Lewes would order them out on one of his ‘night schemes’forced marches across the desert with the soldiers required to navigate their way successfully from point to point. Any soldier Lewes considered not up to scratch, either physically or emotionally, was RTU’d, leading some recruits to perform extraordinary acts of endurance. On one 60-mile march the boots of Private Doug Keith disintegrated after 20 miles so he completed the remaining distance in stockinged feet with a 75lb pack on his back.

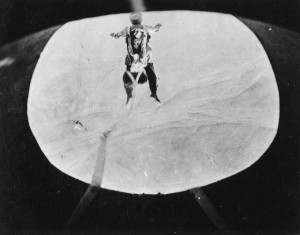

What the men hated above all else, however, was parachute training. Without an aircraft Lewes initially improvised by drawing on the practicality of one of the recruits, Jim Almonds, to construct a wooden jumping platform and trolley system from which the men leapt to simulate hitting the ground at speed. Lewes decided this was too tame and resorted to another method, as recalled by Mick D’Arcy who said ‘there were a great number of injuries during ground training jumping off trucks at 30–35 mph’.(7) Du Vivier broke his wrist leaping from the tailgate of a truck, and he wasn’t the only recruit to end up in hospital as a consequence of Lewes’s ingenuity; nevertheless hurling oneself from a moving vehicle was preferable to jumping out of an aircraft at 800ft.

The day Du Vivier completed his first parachute jump proper was 16 October, a Thursday, and like the other nine men in the Bristol Bombay aircraft he ran the gamut of emotions. ‘My knees began to beat a tattoo on one another as I stretched up to adjust my static line,’ he wrote in his diary. ‘We moved towards the door and I glanced down. Mother Earth looked miles away and I wished I’d never been born … what happened next I can only faintly remember. The earth seemed to be above me and the sky below, then suddenly a big white cloud burst over me and I began to recognise it as being my ’chute. Everything steadied itself and I found myself sitting comfortably in my harness. My brain cleared and I felt an overwhelming feeling of exhilaration.’

But two of the men weren’t so fortunate. Ken Warburton and Joe Duffy were in the next stick of ten aspiring parachutists. First out was Warburton, then Duffy, who seemed to hesitate for a moment before he leapt, as if he sensed something wasn’t quite right. He jumped nonetheless and it was only then that the dispatcher, Ted Pacey, saw that the snap-links on the men’s static line had buckled. He pulled back Bill Morris, the third in line, but it was too late for Warburton and Duffy. ‘When we got to Duffy his parachute was half out, he had tried to pull it out but couldn’t twist round and get it out,’ recalled Jimmy Storie, who had seen the tragedy from the ground. ‘After that we all used to give the static line a good tug first before jumping.’

The problem with the static line was quickly solved and the next day Stirling jumped first to inspire his men. Outwardly he remained his usual insouciant self but inside he was livid with the British Army parachute training school at Ringway, Manchester, who had ignored his numerous appeals for assistance. ‘I sent a final appeal to Ringway,’ he reflected after the death of Duffy and Warburton, ‘and they sent some training notes and general information, which arrived at the end of October … included in this information we discovered that Ringway had had a fatal accident caused by exactly the same defect as in our case.’(8)

Perhaps in acknowledgement of their role in the deaths of Duffy and Warburton, Ringway sent one of their best instructors to North Africa. Captain Peter Warr arrived at Kabrit on 15 November, the day Stirling celebrated his 26th birthday and the eve of L Detachment’s first operation.

As Stirling had informed Auchinleck in July it was common knowledge that an Eighth Army offensive would be launched against Axis forces in November. It was codenamed ‘Crusader’ and its aims were to retake the eastern coastal regions of Libya (a region known as Cyrenaica) and seize the Libyan airfields from the enemy, thereby enabling the RAF to increase their supplies to Malta, the Mediterranean island that was of such strategic importance to the British. But General Erwin Rommel also prized Malta and was busy finalising his own plans for an offensive; he intended his Afrika Korps to drive the British eastwards, take possession of the airfields and prevent the RAF reaching Malta with their precious cargoes. In addition, the fewer British planes there were to attack German shipping in the Mediterranean, the more vessels would reach North African ports with the supplies he needed to win the Desert War.

Stirling’s plan was to drop his men between these two vast opposing armies and attack the Axis airfields at Gazala and Timimi in eastern Libya at midnight on 17 November. On the day of his birthday Stirling wrote to his mother, telling her that: ‘It is the best possible type of operation and will be far more exciting than dangerous.’(9)

That same day, wrote Du Vivier in his diary, Stirling revealed the nature of their operation for the first time. ‘The plans and maps were unsealed, explained and studied until each man knew his job by heart. There was a lot of work to be done such as preparing explosives, weapons and rations.’

Stirling hadn’t a full complement of men for the operation. Several soldiers, including Lieutenant Bill Fraser and Private Jock Byrne, were recovering from injuries sustained during parachute training. In total Stirling had at his disposal 54 men, whom he divided into four sections under his overall command. Lewes was to lead numbers one and two sections and Blair Mayne would be in charge sections three and four.

Mayne, by this stage, was known to one and all as ‘Paddy’. If Lewes was the brains of L Detachment during its formative days, then Mayne was the brawn, a fearsomely strong man, both mentally and physically, who like Lewes set himself exacting standards. The difference between the pair was that Mayne had a wild side that he set free with alcohol when the occasion arose. Jimmy Storie had known Mayne since the summer of 1940 when they both enlisted in No.11 Scottish Commando. ‘Paddy was a rough Irishman who was at his happiest fighting,’ Storie recalls. ‘He didn’t like sitting around doing nothing. In Arran [where the commandos trained in the winter of 1940] he was known to sit on his bed and shoot the glass panes out of the window with his revolver.’

Just about the only members of L Detachment unafraid of Mayne were Reg Seekings and Pat Riley. Riley had been born in Wisconsin in 1915 before moving to Cumbria with his family where he went to work in a granite quarry aged 14. Three years later he joined the Coldstream Guards and he was reputed to be the physical match of the 6ft 4in Mayne. Seekings was smaller, but he could work his fists better than the Irishman. ‘Mayne’s appearance was a bit over-awing and he had a very powerful presence,’ recalled Seekings. ‘But I never had any trouble with him when drinking, nor Pat Riley, because we weren’t worried about his size and we both had the confidence we could deal with him. And Paddy respected us for that so there was no problem… Paddy said once “Of course, Reg, I’d be too big for you” and I said “the bigger they are the harder they fall.” He laughed and said “sure, we’ll have to try it sometime”. It became a standing joke but we had too much respect for each other … the problem with Paddy was that people were frightened of him and that used to annoy him to such an extent that sparks would fly, particularly if he’d had a drink.’

One of Mayne’s fellow officers in Layforce was Lieutenant Gerald Bryan, a recipient of the Military Cross for his gallantry at Litani River. He recalled of the Irishman: ‘When sober, a gentler, more mild-mannered man you could not wish to meet, but when drunk, or in battle, he was frightening. I’m not saying he was a drunk, but he could drink a bottle of whisky in an evening before he got a glow on… One night, when he had been on the bottle, he literally picked me up by the lapels of my uniform, clear of the ground, with one hand while punching me with the other hand, sent me flying. Next day he didn’t remember a thing about it. “Just tell me who did that to you Gerald,” he said. I told him I’d walked into a door. He was a very brave man and I liked him very much.’(10)

Mayne’s two sections comprised 21 men in total and his second-in-command was Lieutenant Charles Bonington. Their objective was the airfield at Timimi, a coastal strip west of Tobruk which was flat and rocky and pitted with shallow wadis. It was hot during the day and cool at night and apart from esparto grass and acacia scrub there was scant vegetation. The plan was simple: once the two sections had rendezvoused in the desert following the night-time parachute drop on 16 November, they would march to within five miles of the target before lying up during the daylight hours of 17 November. The attack would commence at one minute to midnight on the 17th with Bonington leading three section on to the airfield from the east. Mayne and four section would come in from the south and west, and for 15 minutes they were to plant their bombs on the aircraft without alerting the enemy to their presence. At quarter past midnight the raiders could use their weapons and instantaneous fuses at their discretion.

At dawn on 16 November Stirling and his 54 men left Kabrit for their forward landing ground of Bagoush, approximately 300 miles to the west. Once there they found the RAF had been thoughtful in their welcome. ‘The officers’ mess was put at our disposal and we kicked off with a first-rate meal after which there were books, games, wireless and a bottle of beer each, all to keep our minds off the coming event,’ wrote Du Vivier in his diary.

He was in Jock Lewes’s 11-man section, along with Jimmy Storie, Johnny Cooper and Pat Riley, and it wasn’t long before they sensed something wasn’t quite right. Stirling and the other officers were unusually tense and all was revealed a little while before the operation was due to commence when they were addressed by their commanding officer. Stirling informed his men that weather reports indicated a fierce storm was brewing over the target area, one that would include winds of 30 knots. The Brigadier General Staff coordinator, Sandy Galloway, was of the opinion that the mission should be aborted. Dropping by parachute in those wind speeds, and on a moonless night, would be hazardous in the extreme. Stirling was loathe to scrub the mission; after all, when might they get another chance to prove their worth? He asked his men what they thought and unanimously they agreed to press ahead.

At 1830 hours a fleet of trucks arrived at the officers’ mess to transport the men to the five Bristol Bombay aircraft that would fly them to the target area. Du Vivier ‘muttered a silent prayer and put myself in God’s hands’ as he climbed aboard.

Du Vivier’s was the third aircraft to take off, behind Stirling’s and Lieutenant Eoin McGonigal’s. Bonington and his nine men were on the fourth plane and Mayne’s section was on the fifth. Each aircraft carried five (or in some cases, six) canisters inside which were two packs containing weapons, spare ammunition, fuses, explosives, blankets and rations.

The men would jump wearing standard issue desert shirts and shorts with skeleton web equipment on their backs containing an entrenching tool. A small haversack was carried by each man inside which was grenades, food (consisting of dates, raisins, cheese, biscuits, sweets and chocolate), a revolver, maps and a compass. Mechanics’ overalls were worn over all of this to ensure none of the equipment was caught in the parachute rigging lines during the drop.

Mayne’s aircraft took-off 40 minutes behind schedule, at 2020 hours instead of 1940 hours, though unlike the other planes they reached the drop zone (DZ) without attracting the unwanted attention of enemy anti-aircraft (AA) batteries. At 2230 hours they jumped with Mayne describing subsequent events in his operational report:

As the section was descending there were flashes on the ground and reports which I then thought was small-arms fire. But on reaching the ground no enemy was found so I concluded that the report had been caused by detonators exploding in packs whose parachutes had failed to open.

The landing was unpleasant. I estimated the wind speed at 20–25 miles per hour, and the ground was studded with thorny bushes.

Two men were injured here. Pct [parachutist] Arnold sprained both ankles and Pct Kendall bruised or damaged his leg.

An extensive search was made for the containers, lasting until 0130 hours 17/11/41, but only four packs and two TSMGs [Thompson sub-machine guns] were located.

I left the two injured men there, instructed them to remain there that night, and in the morning find and bury any containers in the area, and then to make to the RV [rendezvous point] which I estimated at 15 miles away.

It was too late to carry out my original plan of lying west of Timimi as I had only five hours of darkness left, so I decided to lie up on the southern side. I then had eight men, 16 bombs, 14 water bottles and food as originally laid for four men, and four blankets.(11)

Mayne and his men marched for three-and-a-half miles before laying up in a wadi. He estimated they’d covered six miles and were approximately five miles from the target. When daylight broke on the 17th, a dawn reconnaissance revealed they were six miles from the airfield, on which were 17 aircraft.

Back in the wadi, Mayne informed his men of the plan: they would move forward to attack the target at 2050 hours with each man carrying two bombs. He and Sergeant Edward McDonald would carry the Thompson sub-machine guns. Until then they would lie up in the wadi. But as Mayne noted later in his report the weather intervened:

At 1730 hours it commenced to rain heavily. After about half an hour the wadi became a river, and as the men were lying concealed in the middle of bushes it took them some time getting to higher ground. It kept on raining and we were unable to find shelter. An hour later I tried two of the time pencils and they did not work. Even if we had been able to keep them dry, it would not, in my opinion, have been practicable to have used them, as during the half-hour delay on the plane the rain would have rendered them useless. I tried the instantaneous fuses and they did not work either.

Mayne postponed the attack and he and his men endured a miserable night in the wadi. The rain eased the next morning, 18 November, but the sky was grey and the temperature cool; realising that the fuses wouldn’t dry, Mayne aborted the mission and headed south. Though bitterly disappointed that he hadn’t been able to attack the enemy, the Irishman was nonetheless pleased with the way his men had conducted themselves in arduous circumstances: ‘The whole section,’ he wrote, ‘behaved extremely well and although lacerated and bruised in varying degrees by their landing, and wet and numb with cold, remained cheerful.’

Mayne led his men to the RV, a point near the Rotondo Segnali on a desert track called the Trig-al-Abd 34 miles inland from both Gazala and Timimi airfields, at dawn on 20 November. Waiting for them were members of the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), who a few hours earlier had taken custody of Jock Lewes’s stick. They welcomed members of Mayne’s section with bully beef and mugs of tea and the men swapped horror stories. ‘It was extraordinary really that our entire stick landed without injury because the wind when you jumped was ferocious and of course you couldn’t see the ground coming up,’ recalled Johnny Cooper. ‘I hit the desert with quite a bump and was then dragged along by the wind at quite a speed. When I came to rest I staggered rather groggily to my feet, feeling sure I would find a few broken bones but to my astonishment I seemed to [have] nothing worse than the wind momentarily knocked out of me. There was a sudden rush of relief but then of course, I looked around me and realised I was all alone and, well, God knows where.’

Lewes and his men had jumped in a well-organised stick, the Welshman dropping first with each successive man instructed to bury his parachute upon landing and wait where he was. Lewes intended to move back along the compass bearing of the aircraft, collecting No.2 jumper, then No.3 and so on, what he called ‘rolling up the stick’. But the wind had dragged Jeff Du Vivier for 150 yards until finally he snagged on a thorn bush, allowing him a chance to take stock of the situation. ‘When I finally freed myself, I was bruised and bleeding and there was a sharp pain in my right leg,’ he wrote in his diary. ‘When I saw the rocky ground I’d travelled over, I thanked my lucky stars that I was alive.’

Eventually Du Vivier found the rest of the stick and joined his comrades in searching for the containers. ‘We couldn’t find most of the containers with our equipment so Jock Lewes gathered us round and said that we’d still try and carry out the attack if we can find the target,’ said Cooper.

They marched through the night and laid up at 2130 hours the next morning. Sergeant Pat Riley was sent forward to reconnoitre the area and returned to tell Lewes that there was no sign of the Gazala airfield and in his opinion they had been dropped much further south than planned. Nonetheless Lewes decided to continue and at 1400 hours they departed the wadi and headed north for eight miles. But in the late afternoon the weather turned against them once more and the heavens opened, soaking the men and their explosives. ‘The lightning was terrific,’ recalled Du Vivier. ‘And how it rained! The compass was going round in circles. We were getting nowhere. And we were wallowing up to our knees in water. I remember seeing tortoises swimming about.’

Lewes, with the same grim reluctance as Mayne, informed the men that the operation was aborted and they would head south towards the RV. The hours that followed tested the resolve of all the men, even Lewes who, cold, hungry and exhausted like the rest of his section, temporarily handed command to Riley, the one man who seemed oblivious to the tempest. Du Vivier acknowledged Riley’s strength in his diary: ‘I must mention here Pat Riley, an ex-Guardsman and policeman… I shall always be indebted to him for what he did. I’m sure he was for the most part responsible for our return.’

Riley had the men march for 40 minutes, rest for 20 minutes if there was any dry ground to be found, march for 40 minutes and so on. On through the night they stumbled, often wading through water that was up to their knees. Inadequately dressed against the driving rain and freezing wind, Du Vivier had never experienced such cold. ‘I was shivering, not shaking. All the bones in my body were numbed. I couldn’t speak, every time I opened my mouth my teeth just cracked against one another.’

The rain eased and the wind dropped the next morning (18 November) but it was another 36 hours before Lewes and his section made contact with the LRDG. The return of Mayne’s stick took the number of survivors to 19. A few hours later the figure increased by two when David Stirling and Sergeant Bob Tait were brought in by a LRDG patrol. In Tait’s operational report he described how their aircraft was delayed in its approach to Gazala by strong winds and heavy AA fire. When they did eventually jump they ‘all made very bad landings which resulted in various minor injuries. They had considerable difficulty in assembling, and sergt Cheyne was not seen again.’*

[* In some wartime histories of the SAS L Detachment veterans recall Sergeant John Cheyne as having broken his back jumping with Lewes’s section, but one must assume Tait’s report to be the more reliable as it was contemporary.]

Unable to find most of their containers, and with many of his men barely able to walk, Stirling decided that he and Tait (the only man of the stick to land unscathed) would attack the airfield while the rest, under the command of Sergeant-Major George Yates, would head to the RV. But Stirling met with the same fate at Mayne and Lewes, abandoning the mission in the face of what the noted war correspondent Alexander Clifford called ‘the most spectacular thunderstorm within local memory’.(12)

For a further eight hours Stirling and his men waited at the RV in the hope of welcoming more stragglers, but none showed and finally they agreed to depart with the LRDG. The next day, 21 November, the LRDG searched an eight-mile front in the hope of picking up more of L detachment, but none were seen.

Stirling later discovered that the aircraft carrying Charles Bonington’s section had been shot down by a German Messerschmitt. The pilot, Charles West, was badly wounded, his co-pilot killed and the ten SAS men suffered varying degrees of injury. Doug Keith, the man who had marched for 40 miles in his stockinged feet during training, succumbed to his injuries and his comrades were caught by German troops. Yates and the rest of Stirling’s section were also taken prisoner but of McGonigal’s section there was no word; their fate remained a mystery until October 1944 when two of the stick, Jim Blakeney and Roy Davies, arrived in Britain having escaped from their prisoner-of-war (POW) camp. Blakeney’s account of the night of 16 November 1941 was explained in an SAS report: ‘After landing he lay up until dawn and found himself alone with other members of his party, including Lt McGonigal, who was badly injured and died later [as did Sidney Hildreth]… This party, which endeavoured to make for the LRDG RV got lost and made their way to the coast, and were picked up by an Italian guard at Timimi airport.’(13)

Mayne was deeply affected by McGonigal’s failure to reach the RV and while at a later stage of the Desert War, when Gazala was in Allied hands, he would go there to search for the grave of his friend, but for the moment he brooded on his disappearance, vowing to have his revenge on the enemy.

Stirling was also brooding on the way to the Eighth Army’s forward landing ground at Jaghbub Oasis. Thirty-four of his men were missing, either captured or dead, and yet no one from L Detachment had even fired a shot in anger at the enemy. But despite the abject failure of the operation Stirling wasn’t totally despondent; already he had decided that in future the SAS would reach the target area not by parachute but by in trucks driven by the LRDG. In this way, as Stirling later commented, the LRDG would be ‘able to drop us more comfortably and more accurately within striking distance of the target area’.(14)

The remnants of L Detachment reached Jaghbub Oasis on the afternoon of 25 November. As well as housing the Eighth Army’s forward landing ground there was also, set among the ruins of a well-known Islamic school, a first-aid post. Before despatching the wounded into the care of the medics, Stirling assembled his men to tell them that L Detachment was far from finished despite the obvious disappointment of its inaugural operation. He promised there would be ‘a next time’ to which Jeff Du Vivier replied in his diary: ‘I don’t fancy a next time if this is what it’s going to be like.’*

[*One upshot of the failed raid was the shelving of a plan to raise a Middle East airborne battalion. Shortly before the operation, Stirling had been asked to submit his thoughts on the idea and he had written an enthusiastic appraisal, stating that ‘such an establishment should amply allow for the weeding out of unsuitable and the physically unfit; it could broadly consist of 4 Coys. of 100 men each, a small operative HQ group and a non-operative Administrative Coy. of 100 men.’]

Endnotes

Chapter One

- Alan Hoe, David Stirling (Warner, 1994)

- Author interview, 2003

- Author interview with John Kane, 1998

- Author interview, 2001

- David Stirling, Origins of the Special Air Service, SAS Archives

- Author interview, 2003

- Memo entitled The First Parachute Jump in the Middle East, National Archives

- David Stirling, Origins of the Special Air Service

- Ibid.

- Graham Lappin, 11 Scottish Commando (unpublished but available to view at www.combinedops.com)

- Mike Blackman (ed.), The Paddy Mayne Diary (unpublished, 1945)

- Gavin Mortimer, Stirling’s Men (Weidenfeld, 2004)

- SAS report on the repatriation of Blakeney, 1944, National Archives, AIR50/205

- Hoe, David Stirling

Excerpted from The SAS in World War II: An Illustrated History by Gavin Mortimer.

Copyright 2011 by Gavin Mortimer.

Reprinted with permission from Osprey Publishing.

GAVIN MORTIMER is the author of Stirling’s Men, a ground-breaking history of the early operations of the SAS; The Longest Night: Voices from the London Blitz, The Blitz: An Illustrated History and The SAS in World War II: An Illustrated History. An award-winning writer whose books have been published on both sides of the Atlantic, Gavin has previously written forThe Telegraph, The Sunday Telegraph, The Observer and Esquire magazine. He continues to contribute to a wide range of newspapers and magazines from BBC History to the American Military History Quarterly. In addition he has lectured on the SAS in World War Two at the National Army Museum.