WCAG Heading

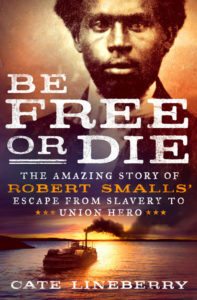

by Cate Lineberry

As the waves rocked the Planter, Robert Smalls proudly presented the guns to the dashing young John Frederick Nickels, the captain of the Onward, who had come very close to destroying their ship a few minutes earlier. The moment was surreal. After years of longing to find a way out of slavery for his family, Robert Smalls had finally done it. He and his family had escaped. He would no longer have to worry about his wife or his children being sold and separated from him. He would no longer have to worry that they would be sent to the Work House or that Hannah would be raped or beaten.

Robert Smalls had accomplished what had seemed nearly impossible and now was turning over a Confederate steamer and four desperately needed cannon.

Nickels must have been shocked as he realized what Robert Smalls and his band of men had achieved and just how much their act would benefit the Union. Every gun helped further the cause, whether for the North or South, and Robert Smalls was not just adding a cannon to the Union arsenal: he had also taken guns away from the Confederates.

After Robert Smalls announced that he had brought the guns, Nickels boarded the Planter. The group of newly freed men immediately surrounded him and asked if he had an American flag he could spare. Nickels soon took down the makeshift white flag hanging from the Planter and replaced it with an American one. The Planter was now a Union vessel.

The women and children appeared on deck, and the women began shouting with happiness. Hannah was so excited she raised baby Robert over her head and told him to look at the flag. “It’ll do you good,” she said.

Robert Smalls gave Nickels the newspapers the crew had brought out of Charleston the day before. They would help the Union understand what the did and did not know about the Union military and would give Nickels and other officers a glimpse of daily life in the city.

Robert Smalls also turned over a book from the Planter that included the secret code for reading Confederate wigwag signals. Wigwags were coded messages transmitted across line-of-sight distances by an officer performing specific combinations of motions with a flag; each motion represented an alphanumeric character determined by the signaling code. At night the Confederates used torches instead of flags. The book’s value to the Union was significant. Before the Confederates realized that the code had been compromised, the Union had been able to read signals sent from Fort Sumter, Fort Moultrie, and Morris Island to headquarters in Charleston.

Nickels soon welcomed Robert Smalls and the rest of the company to the Onward as the group continued to celebrate their newfound freedom. Just hours before, masters had controlled their lives. Now, although they were still considered contrabands by the U.S. government rather than completely free, they had a chance to create their own futures.

As Nickels provided the commanding officer of the Union fleet with the details of what had happened, the city of Charleston awoke to martial law and the embarrassing realization that the Planter had been taken. Its citizens shuddered in disbelief.

Initially, the city’s whites simply could not believe that anyone could have taken the steamer from the harbor, let alone that slaves had done so. “The news at first was not credited,” reported the Charleston Daily Courier, as rumors of what had happened swirled around the city. “It was not until, by the use of glasses, [the Planter] was discovered, lying between the federal frigates, that all doubt on the subject was dispelled.”

John Ferguson, the owner of the Planter, must have been furious when he heard what happened, particularly when he realized that the white officers were not on board. The Confederacy would probably reimburse Ferguson for the value of the steamer, but he would no longer receive the handsome leasing fees he had charged.

Equally angry that the ship had been taken was Gen. Roswell Ripley, commander of the Second Military District of South Carolina. Ripley’s aide-de-camp had the unpleasant task that morning of reporting to the General, who was known for his outbursts, that slaves had taken his dispatch boat. He also had to tell Ripley that the guard in the neighborhood of the wharf had been questioned and reported seeing two white men and a white woman board the vessel at about eight o’clock in the evening. The guard had noticed the visitors when they arrived, but he did not see them leave and had not thought to investigate further.

The trio, the guard had surmised, had been on board with the enslaved crew when the vessel left the harbor. While the guard’s report was completely inaccurate, it highlighted the Confederacy’s lax security and the absence of the Planter’s white officers.

The rumor that whites had helped orchestrate the escape quickly spread and seemed to make it easier for many in Charleston to believe what had happened. One Confederate soldier wrote to his mother, “The affair of the steamer Planter seems to be creating some excitement… I scarcely think that negroes devised that scheme. Some white person must be at the bottom of it.”

Ripley must also have been mortified. A group of enslaved men had taken his personal barge a few weeks before, and now another group had taken a steamer used as his dispatch boat and moored it next to his headquarters. He also must have been greatly concerned that Smalls and the other men on the Planter knew a lot about Charleston’s defenses, including that the Confederates had abandoned Cole’s Island (the location from which they had been ordered to remove Confederate guns the day before they took the steamer).

Their work had made them privy to lots of information that the Union would find helpful. The problem was not that the Confederates had trusted the slaves, but that the Confederates relied on them and never anticipated they could escape.

Ripley had no choice but to report the disaster to his superior officer, Maj. Gen. John C. Pemberton. Forty-eight-year-old Pemberton was the commander of the Confederate Department of South Carolina and Georgia; he had recently replaced Gen. Robert e. Lee, under whom he had served.

Like Ripley, Pemberton was a Confederate officer who was born in the North and had married a Southerner. Despite their shared background, Ripley and Pemberton did not get along. Both were known for being abrasive. Pemberton was blunt and aloof and had endeared himself to many in Charleston, some of whom had made their feelings known to Lee.

When Robert Smalls seized the Planter, Ripley already had been angry with Pemberton because he had ordered the abandonment of Cole’s Island. Ripley considered the defenses at Cole’s Island essential to protecting Charleston and thought Pemberton had made an inexcusable mistake. And now Pemberton’s decision had led to the seizing of the guns both sides so desperately needed.

Had Pemberton not ordered troops to leave Cole’s Island, Robert Smalls would not have been moving the priceless guns, and they would still be in the possession of the Confederacy.

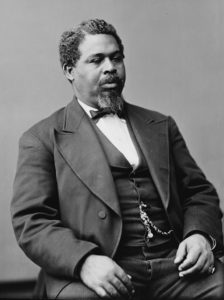

CATE LINEBERRY is a journalist and the author of The Secret Rescue, a #1 Wall Street Journal e-book bestseller and a finalist for the Edgar and Anthony Awards. Lineberry was previously a staff writer and editor for National Geographic Magazine and the web editor for Smithsonian Magazine. Her work has also appeared in the New York Times. Lineberry lives in Raleigh, NC.