By Chris McNab

Along the frontiers of the northern American colonies, where most of the battles of the French and Indian War (1754–63) took place, “Rangers” proved indispensable adjuncts to the main regular and provincial armies, both as partisan warriors and as scouts. They were essentially backwoodsmen—hunters, trappers, militiamen, and Indian fighters—used to operating independently rather than in regimented ranks of soldiery, living off the land and relying on their knowledge of terrain and gun to keep them alive. The very qualities that many commanders despised in the Rangers—field attire that often resembled that of “savage” Indians; unconventional tactics; their occasional obstreperousness; their democratic recruiting standards that allowed blacks and Indians into their ranks—are what helped make them uniquely adroit at fighting their formidable Canadian and Indian wilderness foes, in all kinds of weather conditions and environments.

Battles with Native American warriors in the early 17th century had demonstrated the virtual uselessness of European armor, pikes, cavalry, and maneuvers in the dense New World forests. Although New England militia units had proven themselves courageous and adaptable during the horrific baptism of fire with local tribes known as King Philip’s War (1676–77), it was not until the early 1700s that the colonists could produce frontiersmen capable of penetrating deep into uncharted Indian territory. In 1709, for instance, Captain Benjamin Wright took 14 Rangers on a 400-mile (640km) round trip by canoe, up the Connecticut River, across the Green Mountains, and to the northern end of Lake Champlain, along the way fighting four skirmishes with Indians.

The “Indian hunters” under Massachusetts’ Captain John Lovewell were among the most effective of the early Rangers. Their long, hard-fought battle at Lovewell’s Pond on May 9, 1725, against Pigwacket Abenakis under the bearskin-robed war chief Paugus, became a watershed event in New England frontier history. Its story was told around hearths and campfires for decades, and its example informed future Rangers that Indian warriors were not always invincible in the woods.

When the third war for control of North America broke out in 1744 (commonly called King George’s War, after George II), several veterans of Lovewell’s fight raised their own Ranger companies and passed on their valuable field knowledge. Among the recruits who joined one company assigned to scout the upper Merrimack River valley around Rumford (later Concord), New Hampshire, was the teenager Robert Rogers.

Incessant French and Indian inroads turned the war of 1744–48 into a largely defensive one for the northern colonies. Log stockades and blockhouses protected refugee frontier families; Rumford itself had 12 such “garrison houses.” When not on patrol or pursuing enemy raiders, Rangers acted as armed guards for workers in the field. Bells and cannon from the forts sounded warnings when the enemy was detected in the vicinity.

At the beginning of the last French and Indian War, each newly raised provincial regiment generally included one or two Ranger companies: men lightly dressed and equipped to serve as quick-reaction strike forces as well as scouts and intelligence gatherers. The Duke of Cumberland, Captain General of the British Army, not only encouraged their raising but also advised that some regular troops would have to reinvent themselves along Ranger lines before wilderness campaigns could be won.

Nevertheless, it was not until after the shocking 1757 fall of Fort William Henry that plans were finally accelerated to counterbalance the large numbers of Canadian and Indian partisans. Enlightened redcoat generals such as Brigadier George Augustus Howe, older brother of William, recognized that the forest war could not be won without Rangers. Howe was so firmly convinced of this that in 1758 he persuaded Major-General James Abercromby to revamp his entire army into the image of the Rangers, dress-wise, arms-wise, and drill-wise. Major-General Jeffrey Amherst, who would orchestrate the eventual conquest of Canada, championed Major Robert Rogers and the formation of a Ranger corps as soon as he became the new commander-in-chief in late 1758. “I shall always cheerfully receive Your opinion in relation to the Service you are Engaged in,” he promised Rogers. In the summer of 1759, Amherst’s faith in the Rangers was rewarded when, in the process of laying siege to Fort Carillon at Ticonderoga, they again proved themselves the only unit in the army sufficiently skilled to deal with the enemy’s bushfighters. Even the general’s vaunted Louisbourg light infantry received Amherst’s wrath after two night attacks by Indians had resulted in 18 of their number killed and wounded, mostly from friendly fire.

Before the year was out, Rogers had burned the Abenaki village of Odanak, on the distant St Francis River, its warriors the long-time scourge of the New England frontier. In 1760, after the Rangers had spearheaded the expulsion of French troops from the Richelieu River valley, Amherst sent Rogers and his men to carry the news of Montreal’s surrender to the French outposts lying nearly 1,000 miles (1,600km) to the west. He sent them because they were the only soldiers in his 17,000-man army able to accomplish the task.

Captain Robert Rogers’ Ranger corps became the primary model for the eventual transformation of the regular and provincial army in that region. Colonial irregulars aside from Rogers’ men also contributed to the success of British arms during the war: provincial units such as Israel Putnam’s Connecticut Rangers, companies of Stockbridge Mahican and Connecticut Mohegan Indians, Joseph Gorham’s and George Scott’s Nova Scotia Rangers, and home-based companies such as Captain Hezekiah Dunn’s, on the New Jersey frontier. During Pontiac’s War (1763–64), Ranger companies led by such captains as Thomas Cresap and James Smith mustered to defend Maryland and Pennsylvania border towns and valleys.

Recruitment, Training, and Enlistment

Rogers’ Rangers, the most famous, active, and influential colonial partisan body of the French and Indian War, never enjoyed the long-term establishment of a British regular regiment, with its permanent officer cadre, nor were they classed as a regiment or a battalion as the annually raised provincial troops were. In fact, at its peak Rogers’ command was merely a collection, or corps, of short-term, independently raised Ranger companies. Technically, “Rogers’ Rangers” were the men serving in the single company he commanded. By courtesy, the title was extended to the other Ranger companies (excepting provincial units) with the Hudson valley/Lake George army, since he was the senior Ranger officer there.

Rogers first captained Ranger Company Number One of Colonel Joseph Blanchard’s New Hampshire Regiment in the 1755 Lake George campaign. Thirty-two hardy souls volunteered to remain with him at Fort William Henry that winter to continue scouting and raiding the enemy forts in the north, despite the lack of bounty or salary money.

Near the beginning of the spring of 1756, reports of Rogers’ success in the field prompted Massachusetts’ Governor-General William Shirley (then temporary commander of British forces) to award him “the command of an independent company of Rangers,” to consist of 60 privates, three sergeants, an ensign, and two lieutenants. Robert’s brother, Richard, would be his first lieutenant. No longer on a provincial, footing, Rogers’ Rangers would be paid and fed out of the royal war chest and answerable to British commanders. Although not on a permanent establishment, Ranger officers would receive almost the same pay as redcoat officers, while Ranger privates would earn twice as much as their provincial counterparts, who were themselves paid higher wages than the regulars. (Captain Joseph Gorham’s older Ranger company, based in Nova Scotia, enjoyed a royal commission, and thus a permanency denied those units serving in the Hudson valley.) Rogers was ordered by Shirley “to enlist none but such as were used to traveling and hunting, and in whose courage and fidelity I could confide.”

Because the men of Rogers’ own company, and of those additional companies his veteran officers were assigned to raise, were generally frontier-bred, the amount of basic training they had to undergo was not as protracted as that endured by the average redcoat recruit. A typical Derryfield farmer, for instance, would have entered the Ranger service as an already proficient tracker and hunter. He was probably able to construct a bark or brush lean-to in less than an hour, find direction in the darkest woods, make rope from the inner bark of certain trees, and survive for days on a scanty trail diet.

The typical New Hampshire recruit could also “shoot amazingly well,” as Captain Henry Pringle of the 27th Foot observed. Based at Fort Edward and a volunteer in one of Rogers’ biggest scouting excursions, Pringle wrote in December 1757 of one Ranger officer who, “the other day, at four shots with four balls, killed a brace of Deer, a Pheasant, and a pair of wild ducks – the latter he killed at one Shot.” In fact, many New England troops, according to an eyewitness in Nova Scotia, could “load their firelocks upon their back, and then turn upon their bellies, and take aim at their enemies: there are no better marksmen in the world, for their whole delight is shooting at marks for wages.”

The heavy emphasis on marksmanship in Rogers’ corps, and the issuance of rifled carbines to many of the men, paid off in their frequent success against the Canadians and Indians. (Marksmanship remains among the most important of all Ranger legacies, one that continues to be stressed in the training of today’s high-tech special forces.) Even in Rogers’ only large-scale defeat, the battle on Snowshoes of March 13, 1758, the sharpshooting of his heavily outnumbered Rangers held off the encircling enemy for 90 minutes. Over two dozen Indians alone were killed and wounded, among the dead one of their war chiefs. This was an unusually high casualty rate for the stealthy Native Americans (“who are not accustomed to lose,” said Montcalm of the battle). So enraged were the Indians that they summarily executed a like number of Rangers who had surrendered on the promise of good quarter.

Learning how to operate watercraft on the northern lakes and streams was another crucial skill for every Ranger. Birchbark canoes and bateaux (rowing vessels made for transporting goods) were used in Rogers’ earliest forays on Lake George. In 1756, these were swapped for newly arrived whaleboats made of light cedar planking. Designed for speed, they had keels, round bottoms, and sharp ends, allowing for a quick change of direction and agile handling even on choppy waters. Blankets could be rigged as improvised sails.

Additional things the new recruit had to learn, or at least to perfect, included: how to build a raft; how to ford a rapid river without a raft or boat; how to portage a whaleboat over a mountain range; how to “log” a position in the forest as a makeshift breastwork; how to design and sew a pair of moccasins; how to utter bird and animal calls as “private signals” in the woods; and sometimes how to light and hurl a grenade.

Tactics and Campaigning

Because the modus operandi of Rangers remained unknown to the bulk of the regular army, Rogers was ordered in 1757 to pen a compendium of “rules, or plan of discipline,” for those “Gentlemen Officers” who wanted to learn Ranger methods. To ensure that the lessons were properly understood, 50 regular volunteers from eight regiments formed a special company to fall under Rogers’ tutelage. His job was to instruct them in “our methods of marching, retreating, ambushing, fighting, &c.” Many of these rules, totaling 28 in number, were essentially derived from old Indian tactics and techniques, and were well known to New England frontiersmen.

Rule II, for instance, specified that if your scouting party was small, “march in a single file, keeping at such a distance from each other as to prevent one shot from killing two men.” Rule V recommended that a party leaving enemy country should return home by a different route, to avoid being ambushed on its own tracks. Rule X warned that if the enemy was about to overwhelm you, “let the whole body disperse, and every one take a different road to the place of rendezvous appointed for the evening.”

Other rules required that even the most proficient recruit had to undergo special training in bush-fighting tactics. If 300–400 Rangers were marching “with a design to attack the enemy,” noted Rule VI, “divide your party into three columns … and let the columns march in single files, the columns to the right and left keeping at twenty yards [20m] distance or more from that of the center,” with proper guards in front, rear, and on the flanks. If attacked in front, “form a front of your three columns or main body with the advanced guard, keeping out your flanking parties … to prevent the enemy from pursuing hard on either of your wings, or surrounding you, which is the usual method of the savages.”

Rule VII advised the Rangers to “fall, or squat down,” if forced to take the enemy’s first fire, and “then rise and discharge at them.” Rule IX suggested that “if you are obliged to retreat, let the front of your whole party fire and fall back, till the rear hath done the same, making for the best ground you can, by this means you will oblige the, enemy to pursue you, if they do it at all, in the face of a constant fire.”

Most of Rogers’ activities during the war consisted not of battles and skirmishes but of lightning raids, pursuits, and other special operations. As General Shirley’s 1756 orders stated, Rogers was “to use my best endeavors to distress the French and their allies, by sacking, burning, and destroying their houses, barns, barracks, canoes, battoes, &c.”The “&c” included slaughtering the enemy’s herds of cattle and horses, ambushing and destroying his provision sleighs, setting fire to his fields of grain and piles of cordwood, sneaking into the ditches of his forts to make observations, and seizing prisoners for interrogation.

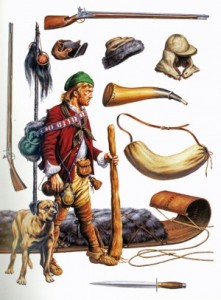

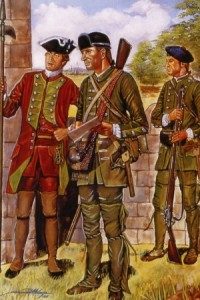

When the big armies under Johnson, Abercromby, Forbes, Wolfe, Amherst, Bouquet, and others marched into enemy territory, Rangers acted as advanced and flank guards, often engaging and repulsing the kind of partisan attacks that had destroyed Braddock’s force. One imperative in bush fighting was camouflage; for Rogers’ men, green attire was a constant throughout the war. Other Anglo-American irregulars, like Gage’s 80th Light Infantry and Putnam’s Connecticut Rangers, wore brown. Some, like Bradstreet’s armed bateau men and Dunn’s New Jersey Rangers, wore gray. A few Ranger companies in Nova Scotia wore dark blue or black.

Green may have been their color of choice, but Rogers’ men never enjoyed a consistent uniform pattern throughout their five-year career, as the regulars and some provincial regiments did. On campaign with Rogers in Nova Scotia in July 1757, a Derryfield farmer-turned-Ranger would have been dressed in “no particular uniform,” according to observer Captain John Knox of the 46th, who added that each Ranger wore his “cloaths short.” This probably signified a variety of coats, jackets, waistcoats, or just shirts, all deliberately trimmed to make them lighter. In the field, the Rangers often resembled Indians, exhibiting a “cut-throat, savage appearance,” as one writer at Louisbourg recorded in 1758.

Among the many perils facing a Ranger assigned to a winter scout in the Adirondack Mountains were temperatures sometimes reaching 40 degrees below zero, snowblindness, bleeding feet, hypothermia, frostbite, gangrene, and lost fingers, toes, and noses. Deep slush often layered the frozen lakes, and sometimes a man would fall through a hole in the ice. Rogers routinely sent back those who began limping or complaining during the first days on the trail. Things only got more onerous as they neared the enemy forts: fireless camps had to be endured, unless they found a depression on a high ridge where a deep hole could be scooped out with snowshoes to accommodate a small fire. Around this were arrayed shelters of pine boughs, each containing “mattresses” of evergreen branches overlaid with bearskins. Wrapped in their blankets like human cocoons, the Rangers would dangle their feet over the flames or coals to spend a tolerably comfortable night.

Guarding the Ranger camp in no-man’s land or enemy country required sentry parties numbering six men each, “two of whom must be constantly alert,” noted Rogers, “and when relieved by their fellows, it should be done without noise.” When dawn broke, the entire detachment was awakened, “that being the time when the savages chuse to fall upon their enemies.” Before setting out again, the area around the campsite was probed for enemy tracks.

Drawing provisions, bedding, and extra clothing on hand-sleds prevented the menfrom burning too many calories and exuding dangerously excessive sweat. Expert snowshoers, they could nimbly climb “over several large mountains” in one day, as provincial Jeduthan Baldwin did on a trek with Rogers in March 1756. Aside from additional warm wear such as flannel under jackets, woolen socks, shoepack liners, fur caps, and thick mittens, the marching winter Rangers wore their blankets wrapped, belted, and sometimes hooded around them, much as the Indians did.

Battling the French and Indians in snow that was often chest-deep could be lethal for a Ranger with a broken snowshoe. Ironically, the green clothing worn by Rogers’ men proved a liability when they had a white slope of snow behind them. According to Captain Pringle, during the 1758 battle on Snowshoes, Rogers’ servant was forced to lay “aside his green jacket in the field, as I did likewise my furred Cap, which became a mark to the enemy, and probably was the cause of a slight wound in my face.” Pringle, “unaccustomed to Snow-Shoes,” found himself unable to join the surviving Rangers in their retreat at battle’s end. He and two other men endured seven days of wandering the white forest before surrendering to the French.

Given the nature of their operations, the Rangers had to be particularly disciplined with their rations. On a winter trek in 1759, Ranger sutler James Gordon wrote, “I had a pound or two of bread, a dozen crackers, about two [pounds of] fresh pork and a quart of brandy.” Henry Pringle survived his post-battle ordeal in the forest by subsisting on “a small Bologna sausage, and a little ginger … water, & the bark & berries of trees.” Also eaten was the Indians’ favorite trail food, parched corn – corn that had been parched and then pounded into flour. It was in effect an appetite suppressant: a spoonful of it, followed by a drink of water, expanded in the stomach, making the traveler feel as though he had consumed a large meal.

Obtaining food from the enemy helped sustain Rangers on their return home. Slaughtered cattle herds at Ticonderoga and Crown Point provided tongues (“a very great refreshment,” noted Rogers). David Perry and several other Rangers of Captain Moses Hazen’s company raided a French house near Quebec in 1759, finding “plenty of pickled Salmon, which was quite a rarity to most of us.” In another house they dined on “hasty-pudding.” At St Francis, Rogers’ men packed corn for the long march back, but after eight days, he wrote, their “provisions grew scarce.” For some reason game was also scarce in the northern New England wilderness during the fall of 1759, and the Rangers’ survival skills underwent severe tests even as they were being pursued by a vengeful enemy. Now and then they found an owl, partridge, or muskrat to shoot, but much of the time they dined on amphibians, mushrooms, beech leaves, and tree bark. Volunteer Robert Kirk of the 77th Highland Regiment wrote that “we were obliged to scrape under the snow for acorns, and even to eat our shoes and belts, and broil our powder-horns and thought it delicious eating.”

Things grew so desperate that some Rangers roasted Abenaki bounty scalps for the little circles of flesh they held. One small party of Rangers and light infantry was ambushed and almost entirely destroyed by the French and Indians. When other Rangers discovered the bodies, “on them, accordingly, they fell like Cannibals, and devoured part of them raw,” stuffing the remaining flesh, including heads, into their packs. One Ranger later confessed that he and his starving comrades “hardly deserved the name of human beings.”

Other Campaign Challenges

“We are in a most damnable country,” wrote a lieutenant of the 55th Foot at Lake George in 1758, “fit only for wolves, and its native savages.” In such a demanding environment the Rangers were constantly being pushed to their physical and psychological limits, especially when captives of the enemy. Teenager Thomas Brown, bleeding profusely from three bullet holes after Rogers’ January 1757 battle near Ticonderoga, “concluded, if possible, to crawl into the Woods and there die of my Wounds.” Taken prisoner by Indians, who often threatened his life, he was forced to dance around a fellow Ranger who was being slowly tortured at a stake. Recovering from his wounds, Brown was later traded to a Canadian merchant, with whom he “fared no better than a Slave,” before making his escape. Captain Israel Putnam himself was once saved from a burning stake by the last-minute intervention of a Canadian officer. Ranger William Moore had the heart of a slain comrade forced into his mouth. Later, he had some 200 pine splints stuck into his body, each one about to be set afire by his captors, when a woman of the tribe announced she would adopt him. Two captured Indian Rangers were shackled with irons and shipped to France, where they were sold into “extreme hard labor.”

Tasks that might appear Herculean to others were strictly routine for the Rangers. In July 1756, Rogers and his men chopped open a 6-mile (10km) path across the forested mountains between Lake George and Wood Creek, then hauled five armed whaleboats over it to make a raid on French shipping on Lake Champlain. On their march to St Francis, the Rangers sloshed for nine days through a bog in which they “could scarcely get a Dry Place to sleep on.” Rogers himself is said to have escaped pursuing Indians after his March 1758 battle by sliding down a smooth mountain slope nearly 700ft (210m) long. His four-month mission to Detroit and back in 1760 covered over 1,600 miles (2,500km), one of the most remarkable expeditions in all American history.

At campaign’s end, of course, there were rewards to be enjoyed. In late August 1758, Rogers gave his company “a barrell of Wine treat,” and after a large bonfire was lit, the men “played round it” in celebration of recent British victories. As the Richelieu Valley was being swept of French troops in 1760, provincial captain Samuel Jenks wrote with delight, “Our Rangers … inform us the ladys are very kind in the neighbourhood, which seems we shall fare better when we git into the thick setled parts of the country.” Natural wonders previously unseen by any British soldiers, including Niagara Falls, awaited the 200 Rangers who followed Rogers that year to lay claim to Canada’s Great Lakes country for England, and to win the friendship of some of the very tribes they had so often fought.

Excerpted from America’s Elite: US Special Forces from the American Revolution to the Present Day by Chris McNab.

Excerpted from America’s Elite: US Special Forces from the American Revolution to the Present Day by Chris McNab.

Copyright Osprey Publishing.

Reprinted with permission from Osprey Publishing.

CHRIS MCNAB is an author and editor specializing in military history and military technology. To date he has published more than 40 books, including America’s Elite: US Special Forces from the American Revolution to the Present Day. He is the contributing editor of Hitler’s Armies: A History of the German War Machine 1939–45 and Armies of the Napoleonic Wars. Chris has also written extensively for major encyclopedia series, magazines and newspapers.