Mark Felton

Fans of the 1963 movie The Great Escape know that it was based on the real-life wartime prison break of 76 Allied POWs from Stalag Luft III in Poland. But it wasn’t the only ‘Great Escape’ of World War II. Both before and after The Great Escape there were attempts to get out large numbers of men from German POW camps, using many different and ingenious methods. Here are my top 5 prison breaks of World War II.

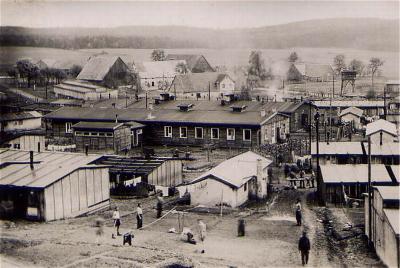

1. The Wire Job Prison Break

Frustrated by constantly losing tunnels to the Germans, the British and Australian prisoners at Oflag VI-B, a massive camp holding thousands of Allied officers at Warburg in northwest Germany, worked out a novel way to overcome the double fences. Lieutenant Jock Hamilton-Baillie invented a scaling apparatus based upon medieval siege warfare. Consisting of a ladder that was leaned against the camp’s inner fence, and an attached duckboard bridge that was pushed out to reach the outer fence, this device enabled teams of 10 men to vault the camp’s huge barbed wire fences. On the night of 30 August 1942, after first fusing the camp’s lights, 40 men in four teams charged the perimeter. In one minute of mayhem, 32 managed to get over and ran off whilst under concentrated fire from enraged German guards. Three men made it to England after four months on the run through Germany, Holland, Belgium, France and Spain.

2. The Dirty Three Dozen

An open latrine seems like an unlikely place to start a tunnel, but this is exactly what RAF prisoner Group Captain Harry Day counted on the Germans thinking too when he and 24 other POWs excavated a tunnel from a lavatory at Oflag XXI-B. Located in Poland, the camp’s prisoners could only access the latrine at certain times of the day, so as well as digging a tunnel, Day and his team also excavated a large underground room where 33 men could hide on the night of the prison break. Air was supplied via a pipe made out of the tin cans and a hand bellows. From 7pm on 5 March 1943 the escapees started exiting the tunnel outside the wire. Working stealthily, the last man crawled out half an hour after midnight and fled into the surrounding forest. Unfortunately, the massive manhunt that followed saw all 33 escapees recaptured.

3. Man Hunt

Oflag VII-B, a camp in Bavaria 60 miles north of Munich, was filled with many officers that had been involved in the Warburg Wire Job, including Jock Hamilton-Baillie. With his comrade Captain Frank Weldon, the two officers and a small team set about excavating a fresh tunnel beneath another latrine. It took them six months of hard labor through very rocky ground before it was ready. On the night of 3-4 June 1943 sixty-five men escaped, most heading south towards Switzerland. It took 50,000 German soldiers, police and Hitler Youths to run them all to ground and recapture everyone, tying down enormous Nazi resources that could have been used elsewhere.

4. La Grande Evasion

The French like to be different, and it’s perhaps no surprise that our Gallic allies launched their own ‘Great Escape’. They even had enough pluck to film their prison break! At Oflag XVII-A in Austria, French officers had constructed a movie camera from parts smuggled into the camp in consignments of sausages. With this they set about recording prison camp life. Like their British allies in other camps, many tunnels had been attempted but all had failed. But when the Germans permitted the French their own open-air performance space called the Theater de la Verdure because it was partly obscured by greenery, they spotted an opportunity. They dug a 270-foot tunnel beneath the theater’s seating. On 17 September 1943 the first group staged their prison break, followed the next night by the rest. An incredible 126 French officers managed to escape, two eventually making their way to freedom. It was truly a of the great prison breaks of World War II. Even more incredibly, the BBC recently aired their 30-minute movie of camp life, titled appropriately ‘Clandestinely’.

5. Breaking In

Stalag XVIII-D had many sub-camps, where Allied prisoners lived on working parties. One such sub-camp held British and Australian POWs who maintained a vital stretch of railway line running from Slovenia into Austria at a place called Ozbalt. Two young privates, one British and one Australian, hatched a daring plan for their small team of seven to escape from their hut. This they managed, linking up with Slovene Partisans in the nearby mountains. But then the escapees had a brainwave. They persuaded the Partisans to give them guns and to come with them and launch an attack on the POW camp to free all of the remaining prisoners. On 31 August 1944 the escaped POWs and their partisan friends duly attacked the camp, disarmed the guards and freed every prisoner they could find. An incredible 70 British, 12 Australian, 10 French and 9 New Zealanders joined the partisans and trekked 160 miles in 14 days, attacked the whole way by German forces, until they reached sanctuary at a partisan-controlled airbase. Though 6 men were killed on the march, the rest of the prisoners were then flown to freedom in Allied-controlled Italy. At the time, the British authorities refused to believe that two ordinary privates had organised the most successful ‘Great Escape’ of the war, but later it was realized that these men had pulled off the seemingly impossible and decorated both.

MARK FELTON has written over a dozen books on prisoners of war, Japanese war crimes and Nazi war criminals, and writes regularly for magazines such as Military History Monthly and World War II. His most recent book is Zero Night: The Untold Story of World War Two’s Greatest Escape, which follows China Station: The British Military in the Middle Kingdom, 1839-1997. He has recently returned to the UK after having spent almost a decade teaching in Shanghai.