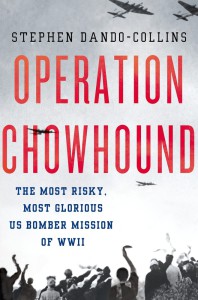

by Stephen Dando-Collins

Seventy years ago, in February, 1945, 3.5 million Dutch civilians in German-occupied Holland, in cities such as Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague, were facing starvation after the Nazis had cut food and power, creating Holland’s ‘Hunger Winter’ of 1944-45. This was the setting for the USAAF’s most risky, most glorious, yet most unsung bomber operation of WWII, relying on the Nazis not firing on hundreds of B-17s flying food drops at just 300 feet.

Players included Allied Supreme Commander General Eisenhower and his chief of staff General Bedell Smith, James Bond creator Ian Fleming, Canadian author Farley Mowat, a German-born prince, the Nazi governor of Holland, and thousands of young American airmen. Meanwhile, one of the youngsters suffering through the Hunger Winter was fifteen-year-old Audrey Hepburn, the future Hollywood star. Audrey and her mother, the Baroness Van Heemstra, had joined Audrey’s grandfather in Holland as war broke out in 1939. By early 1945, they were so short of food, Audrey frequently gave her mother her rations and filled up with water.

Holland’s queen, Wilhelmina, in exile in England, implored the British and American governments to help her starving people. She received a favorable hearing from America’s president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose Dutch ancestors had settled in New York in the 17th century. Roosevelt even told the queen’s daughter Princess Juliana that he considered himself Dutch. Still, as 1945 unfolded, Holland continued to starve and the Allies did nothing.

Meanwhile, Prince Bernhard, Princess Juliana’s husband, pushed within military circles for relief for the Dutch. As chief of Dutch forces, Bernhard mixed with General Eisenhower and Britain’s Field Marshal Montgomery. But many Britons suspected Bernhard’s loyalty. He was German-born, and his brother served in the German army. Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill called in Military Intelligence to check him out.

Senior spy Commander Ian Fleming, later famous as the creator of James Bond, had cultivated Bernhard’s friendship and even knew his favorite drink was a vodka martini, shaken not stirred. But, unaware that, pre-war, Bernhard had been a Nazi party member and likely a German spy in Paris, Fleming gave him a full security clearance.

In Holland, Nazi governor Arthur Seyss-Inquart decided to save himself. With war’s end looming, to avoid a war crimes trial he conceived a good deed. The German counter-espionage service in Holland had penetrated the Dutch Resistance, and Seyss-Inquart called in startled Resistance leaders, proposing to secretly allow the Allies to feed the Dutch, behind Adolf Hitler’s back and against his orders.

A month before Roosevelt died on April 12 the President assured Queen Wilhelmina that he’d instructed General Eisenhower to get food relief to the Dutch. But no such order was received at Eisenhower’s headquarters by April 17, when Ike’s chief of staff General Walter Bedell Smith called in British air commodore Andrew Geddes, instructing him to devise a plan to feed the Dutch from the air.

With insufficient transport aircraft or parachutes, Geddes allocated hundreds of American B-17 and British Lancaster heavy bombers, flying at 300 feet and opening their bomb bays to let rations tumble out. In less than two weeks, Geddes pulled together history’s greatest airborne mercy mission to that date. A mission Geddes would rate ‘as historically important as D-Day.’

Secret meetings between senior Allied and German officers at Achterveld agreed that the 120,000 German troops in Holland wouldn’t fire on Allied bombers flying low along prescribed air corridors, and on April 29 two ‘guinea pig’ bombers dropped food outside The Hague, without incident. That afternoon, 240 more food bombers flew to six Dutch targets. Still, German guns held their fire.

The next day, General Bedell Smith met Seyss-Inquart at Achterveld to formalize continuing food drops. Tough, gruff Bedell Smith, ‘Ike’s hatchet man,’ also tried to convince Seyss-Inquart to surrender Holland, reminding him he could face a firing squad if he didn’t cooperate.

“That leaves me cold,” said the Nazi governor.

“It usually does,” replied the American general.

On May 1, 394 American B-17s commenced their food drop campaign, under the codename Operation Chowhound. Under the codename Operation Manna, Lancasters flown by Britons, Canadians and Australians followed. Geddes’ plan called for 900 bombers a day for as long as it took. But the Nazis still hadn’t signed the Achterveld agreement. Would they keep their word? Would they continue to hold their fire? Or were thousands of American and other Allied airmen flying into a huge trap?